Every school leader struggling to recruit is facing his or her own crisis: empty classrooms require cover — and that’s stressful. But is there a systematic countrywide teacher shortage and, if there is, what’s causing it? We dig into the figures to find out

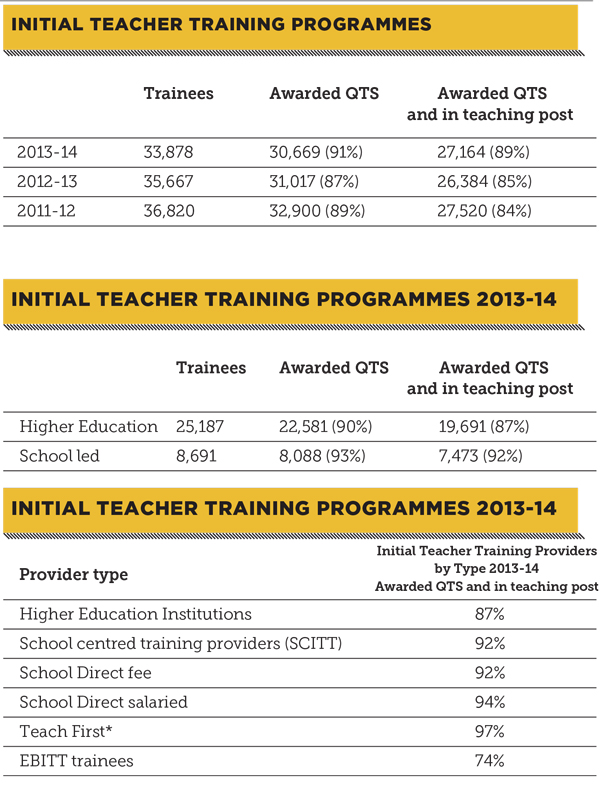

The latest initial teacher training statistics show that almost nine out of ten trainees who gain qualified status (QTS) are in a teaching job six months later – only 11 per cent of those who gained QTS in the 2013-14 academic year were not.

That means of the roughly 30,000 awarded QTS, 27,164 went into teaching posts – an improvement from the previous year, where 15 per cent of newly qualified teachers weren’t in a classroom six months after gaining QTS.

Of those not teaching within six months, 865 were looking for a teaching job and 1,727 were “unknown”. Only 913 of those awarded QTS said they did not want to work as a teacher.

As former government adviser and now TeachFirst director Sam Freedman puts it: “Those who start teaching do stay and succeed.”

One number does stand out as problematic: the numbers studying for QTS has fallen year-on-year. But a higher pass rate in the 2013-14 academic year meant there were only 348 fewer qualified teachers coming out of the system.

And in 2013-14, despite having fewer trainees, more teachers qualified and gained a job within six months (see initial teacher training table).

One potential issue is the difference in drop-out rates between higher education (HE) institutions and school-led training providers. Six months after passing their qualification, 13 per cent of postgraduates trained in the traditional PGCE route were not in teaching compared with 8 per cent of school-led trainees.

As the number following the HE route is more than double the number choosing the school route, this could make a difference.

Professor Alan Smithers, director of the Centre for Education and Employment Research at the University of Buckingham, said: “In-school training may be more efficient. Universities are paid for filling up their places – they don’t have to live with the trainees afterwards.

“They will recruit people with acceptable qualifications, whereas the schools will be judging these people as future colleagues and may well be taking a closer look at the qualifications they have.”

If true, as the number on school-based programmes such as TeachFirst and School Direct increase, the number leaving should reduce.

But this argument only stands when looking at drop-out rates in the first six months of teaching. Over the long-term, there is no consistent data on drop-out rates.

However, in a blog last year, Sam Freedman said that data for TeachFirst’s school-based trainees who gained QTS in 2005 showed that only 42 per cent were teaching four years later – compared with 73 per cent among those who took a mainstream PGCE.

More recent data, for the 2009 TeachFirst cohort, suggests the figure had risen to 56 per cent, but this is still lower than the retention rate of those taking traditional routes.

In 2005, 183 teachers trained through TeachFirst. This year the number is nearing 1,500 and, if plans come to fruition, will continue to rise – so the higher long-term drop-out rate has a bigger effect every year.

While similar figures aren’t available for School Direct, its numbers have also boomed – rising 15 per cent last year. If its graduates have a lower retention rate, this will also contribute to teacher loss.

Professor John Howson (pictured), an education statistician, said the lack of publicly available data makes it tricky to immediately spot, and solve, potential problems.

Data on teachers from 2013/14 were only published at the end of last month. The figures for last year will not be known until August next year.

What the government says

The Department for Education (DfE) says teacher recruitment is improving.

“The quality of teachers in England’s schools is at an all-time high and there are now more teachers in the classroom than ever before.”

But a spokesperson for the department acknowledges: “We recognise recruitment is a challenge as the economy improves and competition for candidates intensifies, which is why we have introduced a range of measures to attract the best people to the profession.”

One of those measures is the recruitment campaign “Your Future is Their Future” which the DfE says is playing a “key role”. It includes bursaries worth £25,000 and scholarships to entice people into the profession.

The department has also recently unveiled a £67 million package to improve science, technology, engineering and maths teaching in England, and to recruit up to 2,500 additional maths and physics teachers.

The DfE also says registrations for its “Get into Teaching” website are up by almost 30 per cent compared with last year, and 3 per cent more graduates are due to start teacher training compared with this time last year.

One reason why the dropout rates might be higher for those taking the university based route into teaching is that these teachers are encouraged to engage with scholarly practice, and therefore learn to become more critical of the context and policy landscape in which they ultimately work. Whereas those who go through school-based routes do not necessarily develop such a critical perspective, they are more likely to acquiesce.

It is not true to say that those going into school-based training routes are more carefully selected. On the Cambridge secondary mathematics programme we have a small number of School Direct trainee teachers (they effectively do the PGCE), the lead school is involved in selection, they are generally more flexible about the qualifications, experience and qualities of recruits than we are for the PGCE – so keen are they to try and get maths teachers.

The recruitment crisis is particularly apparent in secondary mathematics. Last year schools were approaching me -anxious to attract trainees – within the first couple of months of the course. Most of my 26 trainees had jobs just after Christmas.

The basis of the recruitment crisis is a result, I believe, of the attack on the education system by the Coalition Government and now pressed even harder by the Conservatives. Privatisation through academisation (with little evidence that autonomy is beneficial) is leading to a fragmented feudal school system, where accountability trumps quality. This undermines professional judgement and occupational satisfaction. Secondly pay and conditions have been attacked by an insistance on pay restraint through an arbitrary imposition of austerity and the attack on collective bargaining. Professionalism has also been attacked by marginalising the role of higher education, which has always been key in supporting professional voice and teacher activism. The school-led, teacher-knows-best vision offered by Michael Gove is a false offer which disguises the deprofessionalization and fragmentation of the teaching profession. The profession must now stop this by taking collective action.

Its really simple, teachers are significantly under paid with the amount of work they have to do, they work more than 9-5 to just get paid an average salary, this is not acceptable considering the fact that teachers are working long , hard and stressful hours, who is going to want to work a job where they get paid low with a lot of work load ?