Five years ago Laura McInerney and Matt Hood developed a model for how the schools system might work more coherently.

Few people listened. Some parts were echoed in David Blunkett’s review of school management, but, otherwise, it failed.

‘Never mind, the system will work out,’ they thought. Five years on, and it’s still not okay. In fact, it’s even more fragmented. So here they are, trying again to convince the world about the way our school system could become coherent again.

How did we get into such a fragmented mess?

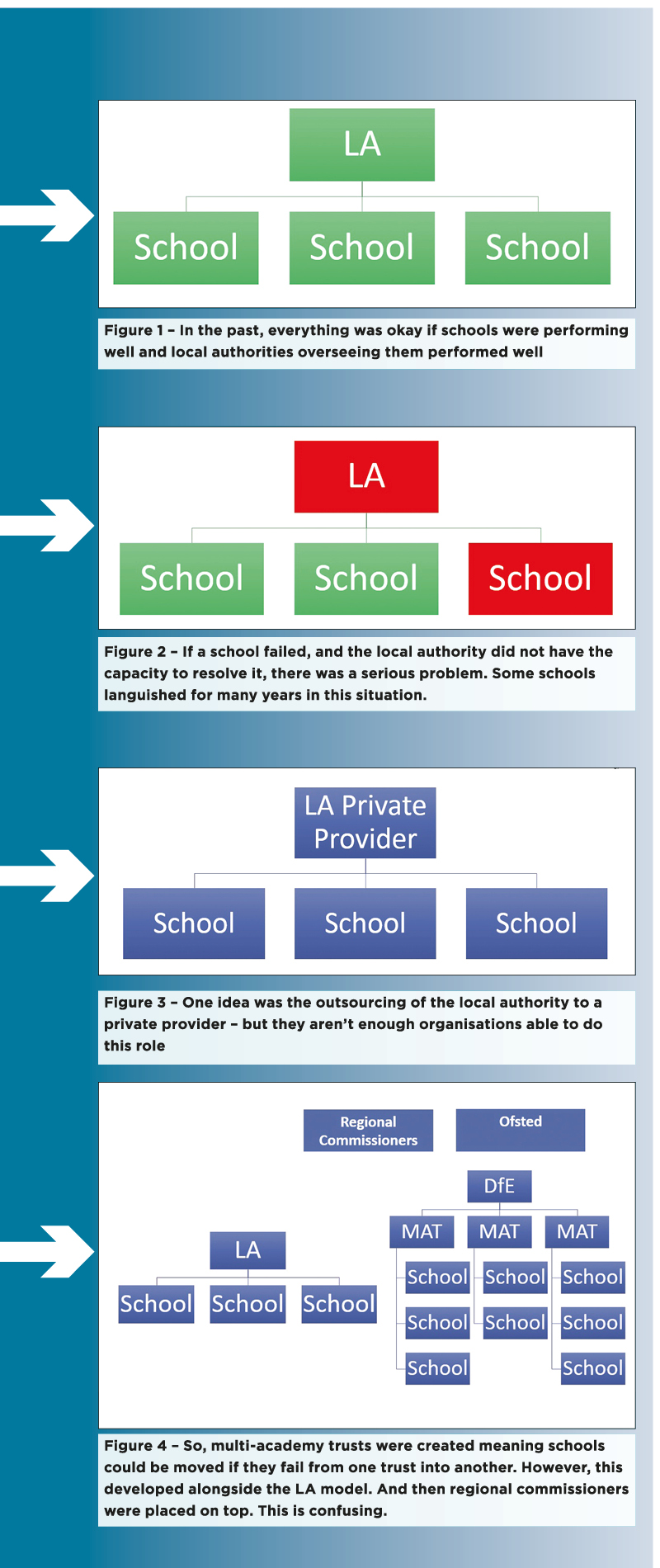

The academy system has one huge benefit. In the past, when schools were overseen purely by local authorities, everything was great as long as schools were performing. If a school failed, but the authority was working out, then turnaround was possible. But if a school struggled and the authority was floundering then it was often a disaster. Under this system, some schools failed systematically for decades.

One idea was to turn the authority around, or outsource it for a short period until it got back on its feet like the Hackney Learning Trust. Finding organisations able to pull this off was a problem, however. Most people who know how to rescue local authorities already work in them and aren’t just sitting at home waiting to be deployed onto a takeover team.

Another solution – the one that the academy system provides – was to change the system so that schools were run by non-profit academy trusts, or multi-academy trusts as they gathered more schools.

Under the charity model, if a school is failing it can be removed from its local authority (or more recently its academy trust) and given to another one. This is much easier because there are lots of trusts (around 1,000) and so it’s always possible to find another when needed. It’s even possible to move every school in a trust and close it down altogether. The recent failure of a 21-school trust in Wakefield proves the point. Within a few months, other trusts said they would take on the schools.

The problem is that around 30 per cent of schools are in this model, and it’s very uneven across phases. While over 70 per cent of secondary schools are in trusts, fewer than 25 per cent of primary schools are. We’re running two parallel systems and that’s messy.

We’ve also got a situation where local authorities have essentially been hollowed out. Manchester used to have loads of school improvement partners to help struggling schools but now it has next to none. So local authorities are hamstrung when they attempt a comparable job to multi-academy trusts, even though they are responsible for most primary schools.

The regional schools commissioners manage the contract between the state and the trust to run a school but, as their role is now expanding, they are also inspecting (or “monitoring”) schools and taking on school improvement roles. Then there’s the partially hilarious situation in which Ofsted can inspect schools and local authorities but can’t inspect multi-academy trusts. So instead they swoop into 15 schools at once and do an unofficial multi-academy trust inspection report that’s as informal as it is un-appealable.

It’s worth saying that we strongly believe, despite the confusion, that the system has lots of really good people doing, with good intentions, the things that they believe are right. Were this mess transitioning towards a more coherent system, we would be okay. Today’s acute problem, though, is that we are not transitioning anywhere.

So how do we create a new model?

We created a model based on three simple principles.

1. People can only do their job and not somebody else’s. In the school system we need everyone to do one job. Each of these roles is tough enough without having to do everyone else’s at the same time. As crazy as this sounds, we just want schools to be teaching their pupils. Likewise, commissioners cannot also be improvers and inspectors can’t be setting policy through speeches and reports.

2. Every decision needs to be open and transparent. Opaque decisions attract sharks and provoke suspicion. Not every discussion must be public, but decisions must be publicly explained and evidence taken into consideration open for scrutiny.

3. There can be no conflicts of interest. This means no related-party transactions – absolutely none. It isn’t permitted in other charitable sectors, so if governors want to offer deal-of-the-cen

Revealed: How the school system should work

The solution is so simple it’s embarrassing.

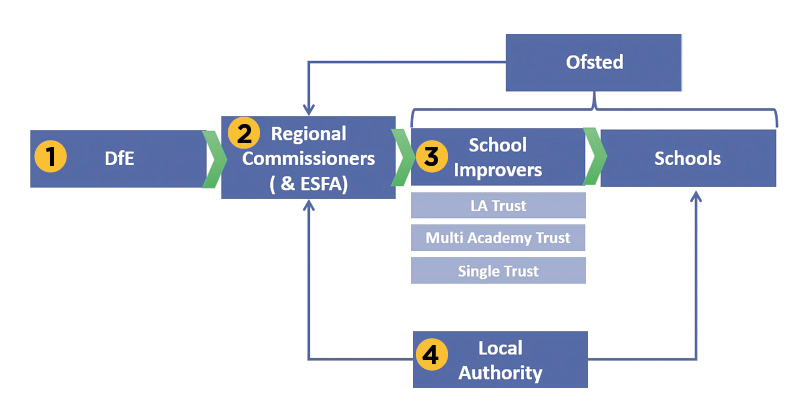

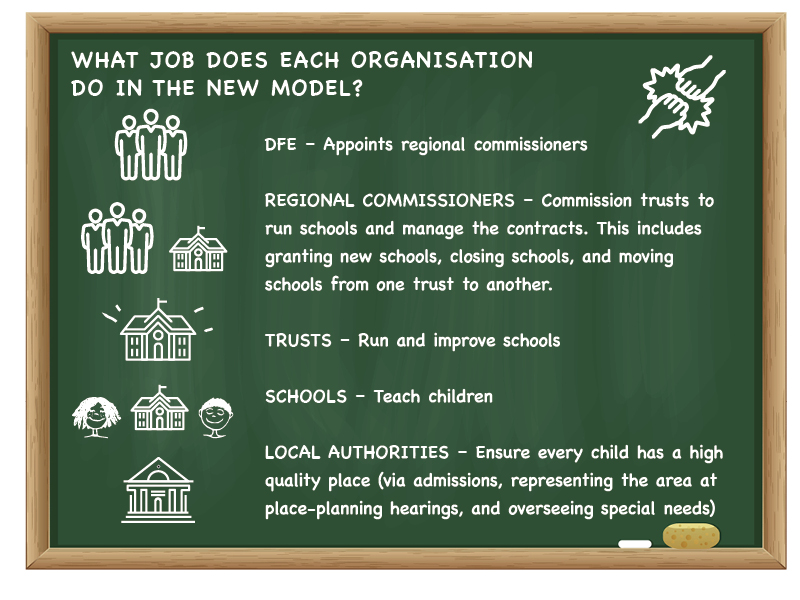

The Department for Education appoints commissioners. Those commissioners then contract – or “commission”, the clue is in the name – multi-academy trusts to run schools. Commissioners also sign off on opening new schools, closures and pupil admission number changes.

The Education Funding Agency (note, we’ve removed “skills”) is basically the administrative arm of the regional schools commissioners, staffed with civil servants who actually write and manage contracts, send out cash and balance the books. They can ask independent auditors to investigate the books of academy trusts, but they can’t do it themselves (per rule two). Any information on finances can be used by the RSCs to terminate or renegotiate contracts if needed.

Next are the “school improvers” – that is, academy trusts. As we see it, the job of trusts is, basically, school improvement. Obviously they have outsiders in to help, but if a multi-academy trust wants to buy in a school improvement partner, or a peer-to-peer network, or 3,000 days of coaching, that’s its own choice. Ultimately, school improvement is for the multi-academy trust to sort – and if it can’t, the school in question moves to someone else.

In our brave new world, schools are not in charge of their own admissions

Note, this category includes multi-academy trusts, standalone academies and local-authority trusts. As a hybrid system is too complex, our solution is to compel local authorities to create arms-length spin-off trusts in which they place their schools, similar to the way council housing was placed into arms-length housing associations in the 2000s.

Local authorities could take 19 per cent of governor places, as they currently can on any academy trust. However, these trusts are not owned by the local authority.

And that’s good because the local authority can then focus on its own jobs (per rule 1), which we believe are admissions, place-planning and commissioning special-needs provisions. If you want that written as one job: making every child gets a quality place.

In our brave new world, schools are not in charge of their own admissions (as that would be a conflict of interest, as per rules 1 and 3), so local authorities do it.

We recognise that commissioners have ultimate control on how many places exist, as they grant school openings, closures and place changes. That said, we’d give local authorities the right to have an open hearing with the commissioner on this issue each year, at which councillors represent local people’s views about place needs. The commissioner would then write a public decision about why they are granting cash/contracts to meet demand (per rule 2). If the RSC think the local authority is wrong, they can say so – and not grant any more schools.

This separates local and national democracy in an important way. In our model, local councillors can be held responsible for the quality of their input to the commissioner (which will be public, both in terms of the meetings and minutes), but it is the national government which should be held responsible for the outcome – that is, the decisions of the commissioners. After all, national government appointed the commissioner and holds the purse strings. Hence, if a town is furious at the regional schools commissioner, it should take it out on their MP. If they are mad at the way its councillors represented local needs, take it to the local elections.

And if you don’t believe any voter does this, we basically agree, but we are also sceptical that ballot-box democracy has ever really held anyone in education to proper account.

The one group left is Ofsted. As we see it, Ofsted is the schools inspectorate. The only inspectors.

Regional schools commissioners cannot have their own monitors sticking their noses into schools. It is Ofsted’s job to inspect both schools and academy trusts, and write up reports which are fed back to commissioners.

Commissioners can ask Ofsted to conduct an inspection if they need more intelligence, but the inspection must be independent. Reports can then be used to close a school if needed, something Ofsted cannot do alone ( due to rule 1), or the report can be ignored. That is up to the commissioner – as long as they explain themselves (rule 2).

And that’s it. All the bits are pointing in the right direction and almost every issue is solved.

Frequently asked questions

What about special needs?

We somewhat waved a hand here and said “LAs are in charge of special needs” as if that’s easy. It’s not.

In fact, Jules Daulby, who knows about these things, has suggested that special needs may even need its own commissioning system which sits behind the LA. We are totally up for that.

Where are headteacher boards?

In the bin. You can’t have school improvers also trying to be the commissioner (rule 3). Open local hearings would replace headteacher board meetings and at hearings anyone could present evidence – including councillors, local headteachers, and parents (rule 2). The RSC then makes decisions via a public written document (rule 2).

What about all the weird grants and school improvement funds that multi-academy trusts apply to the EFA for?

Good point. A lot of those grants break rule 2 and there’s a conflict of interest with the EFA handing out cash when it is also managing contracts around quality. Hence we are happy with the DfE directing policy itself, and putting up funds for its own projects which multi-academy trusts can apply for. For example, the recent cash for breakfast clubs is the perfect example of a fund the DfE could dangle and get people to apply for if it so chooses without wrecking the system.

As for school improvement funding, in our model it’s not a thing. If money is needed because a school has failed and needs turnaround support, that can be built into the rebroker terms when the commissioner writes a new contract. If a school is only temporarily failing and needs emergency cash this could also be part of a (transparent) contract renegotiation.

What about teaching schools alliances?

They can keep existing. If trusts or a school want to be in one to help with their school improvement then that’s great for them, but they’re not a school improver. Their job is to train and develop teachers to teach. Teaching schools may improve by proxy, or a multi-academy trust may choose to buy their services in to aid improvement. As an individual item however, their role is not “school improver”.

We need you

Having spent five years on this, we think it solves many problems. Yes, it still relies on good people filling every role. And we aren’t saying in-dealing will disappear. But it at least puts the system on the road to coherence. And, from that road, we can talk about how to tweak the system and make it better rather than continuing in the messy, ridiculous, borderline-corrupt way the school system works at present.

The question is: what have we missed out? What else does the model need? You tell us. Contact us via twitter (@miss_mcinerney & @matthewhood) or email us.

Have to say I think there is a lot of common sense here. But the issues involved in taking a ‘common sense model’ and applying it to 24,000 schools all over England cannot be understated.

It looks as though your model is based on schools transferring into academy trusts (albeit operating differently to now).

The first questions that springs to mind are practical:

1. What happens if a school doesn’t want to do this. Does your model envisage compelling the school, akin to the highly unpopular ‘forced acadmisation’ policy?

2. We’ve got 16,000-17,000 odd schools that are not converted yet – if your model was adopted how long would you envisage the process taking?

3. You haven’t addressed the ‘toxic school’ problem. If you have a school which has a big deficit and chronic building problems, and either needs a couple of million lump sum to rebuild or hundreds of thousands a year to keep it going, how will you enable that school to join an academy trust?

Finally, one of my hobby horses – you say that related-party transactions are not permitted in other charitable sectors. Sorry, but that’s just wrong. The approach taken in academy trusts mirrors general charity law, and in fact is more regulated thanks to the Articles, funding agreement and Financial Handbook. If you want to check, see what the Charity Commission says about how to “pay a trustee to do work for the charity):

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/payments-to-charity-trustees-what-the-rules-are