The best state schools should change their admissions rules and bus in more disadvantaged pupils to boost aspirations, the Sutton Trust has said, after it revealed disinterest in university trebled between years 9 and 11.

The Sutton Trust has called for the use of ballots and banding on admissions, plus free transport for disadvantaged pupils so they can benefit from a better education, following their latest research into young people’s aspirations.

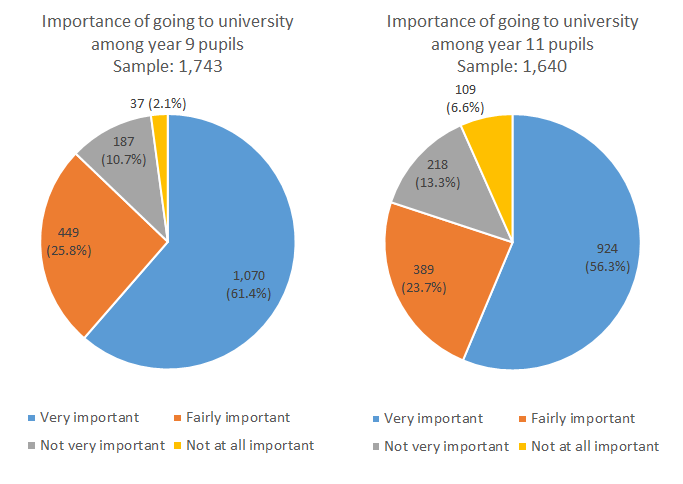

Their study showed that although only 2.1 per cent of year 9 pupils felt getting a degree was “not at all important”, that figure rose to 6.6 per cent when the question was asked of year 11s.

The data also revealed more deprived pupils and those eligible for free school meals were less likely to see attending university as important, leading to calls for poorer pupils to access better schools.

In their report Believing in better: How aspirations and academic self-concept shape young people’s outcomes, academics Pam Sammons, Katalin Toth and Kathy Sylva explored the impact of deprivation and other factors on pupils’ aspirations, using data from the Effective Pre-school, Primary and Secondary Education Project.

Expanding on recommendations in a Sutton Trust report from 2014, which called for more schools to use random allocation ballots or banding to ensure a “wider mix of pupils” had access to their roll, the latest study demands free transport for those pupils who would have to travel if such a system was introduced.

Currently, free school transport is offered to all children aged between five and 16 who go to their nearest school. Those under eight receive it if they live at least two miles from school, while those over eight get it if they live at least three miles away.

Although the Sutton Trust has not drawn up firm recommendations on how the additional free transport would be funded under its proposals, a spokesperson told Schools Week the cost should not fall on schools.

Sir Peter Lampl, the Sutton Trust’s chair, said the report showed the need to raise aspirations and self-belief in pupils from poorer homes, and not just as they reach the end of secondary school.

“We need to offer more support to disadvantaged young people throughout their education so that they are in a position to fulfil their potential after GCSE,” he said.

“Crucially it shows that both aspirations and attainment matter for pupils, so it is vital that schools support both particularly for their poorer pupils.”

Professor Sammons, the report’s lead author, said the report showed that students’ belief in themselves and their aspirations were “shaped by their background”, adding: “Positive beliefs and high aspirations play an additional and significant role in predicting better A-level outcomes.

“These findings points to the practical importance for schools and teachers of promoting both self-belief and attainment as mutually reinforcing outcomes.”

The report has also sparked calls from Russell Hobby, the general secretary of the National Association of Head Teachers, for early intervention and equal opportunities for poorer children.

“It is not just low aspirations that can stop children from disadvantaged backgrounds from getting the best education, or from attending university,” said Hobby, who added that school leaders recognised early years education as a “critical point in the drive to improve life chances”.

“To improve standards at university age, groundwork must have been laid at ages two and three. Access to high quality early years provision is crucial for all children, and we must ensure that children from disadvantaged backgrounds have equal opportunities to attend the best schools – throughout their education,” he said.

Hobby also said that children who qualified for free school meals to have priority access in school admissions, “regardless of where they live”.

Mary Curnock Cook, chief executive of the University and College Admissions Service, said she too was becoming “increasingly aware” of the “importance of early interventions, well before key stage 4”.

“Very bright children, particularly boys, are being thwarted by disengagement rather than ability,” she said.

Where physically possible ie. several schools in a large town or locality Primary Schools should be grouped (maybe 5 or so in a group) and pupils allocated places in one or other of these schools by ballot. Exceptions could be made for siblings. In urban areas it should be possible to do this and not have any child travelling more than a couple of miles. The benefits of this arrangement will be more mixed intakes by social class as well as ability and the ending of parents being given the illusion of choice of school even when some are oversubscribed so that even some living in the catchment area cannot gain entry to the school. We may even see a reduction in house prices in areas where there is a premium paid to be ‘in the catchment area!

Unfortunately with the desire of the present Governemt to destroy LAs and encourage a free for all with Academisation of individual schools and MATs, this aspiration may be more difficult to achieve than ever before. Perhaps a MAT with several schools in close proximity could be encouraged to develop such a system?

It isn’t going to happen is it? The ideology of marketisation assumes that standards are always driven up when providers compete for customers. The performance indicators used for the competition (exam results and league tables driven by them) depend on recruiting the most able and putting off or rejecting the least able. Nothing will change until the marketisation culture and all the negative incentives that result from it are abandoned. See

https://rogertitcombelearningmatters.wordpress.com/2015/06/12/why-do-educational-standards-fall-following-marketisation/