Rain is lashing down outside the drama studio at the Queen Elizabeth II Silver Jubilee School, but inside there’s a cast of storm troopers, a school-uniformed Princess Leia, and Darth Vader (holding a fluffy unicorn), all prepping for Rock Challenge, a fiercely competitive annual dance contest featuring more than 330 schools.

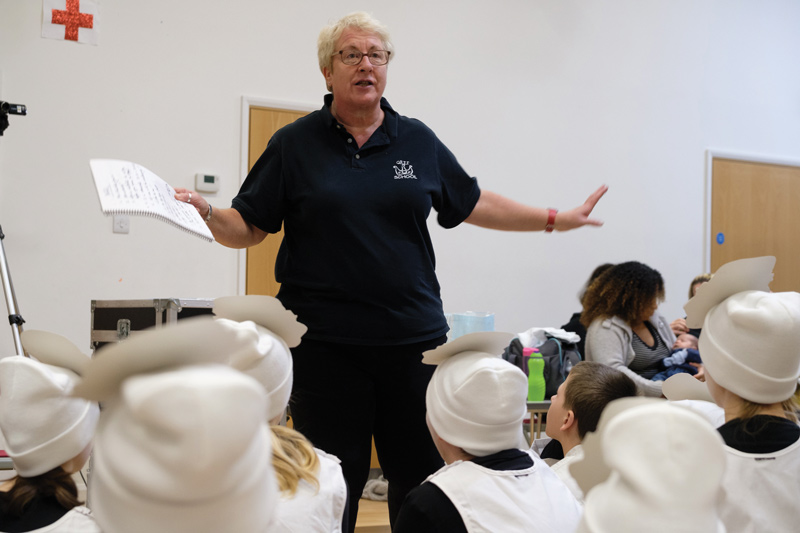

Sue Jay, the school’s head of creative arts, is blunt about the task ahead.

“This is not an easy event,” she tells the students, who are focused on her every word. “There will be 63 people on stage. There will be 85 of us in attendance. You are going to have to concentrate.”

Jay reminds that the dance is a tribute to Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds, “who died earlier this year, so you have to reflect the sadness, when you are supposed to be still and controlled, be still and controlled”.

If they can’t say a Shakespeare line, there are other ways to say things. Physically perhaps.

This serious version of Sue Jay is far removed from the exuberant one who burst onto the stage last year at the Pearson Teaching Awards giving a po-faced Jenny Agutter a squeeze and explaining with gusto why every child in her school takes part in a Shakespeare play every autumn term.

“If they can’t say a Shakespeare line, there are other ways to say things. Physically perhaps, or by bringing a letter in,” she explains. “There are a whole stream of ways I’ve learned of communicating. There are some of our pupils who I tell a line to and they remember it right away, and they will still remember it five years later.”

After conquering Shakespeare, she leads them into a term focused on dance. Jay’s own children all attended Rock Challenge when they were at school. Seeing how much they loved it, she decided to enter her own pupils.

“Can you imagine getting this group to theatre?” she asks. “We can get in, but they put lights in the wings, so you can’t get a wheelchair in. It’s a nightmare. There’s toileting requirements. Then there’s transporting the students over there. Some will have to come back after we first rehearse and lie down. The day is from 10 in the morning until 10 at night, and we perform between 6pm and 9pm.

“We don’t know when: they draw it out of a hat. We could be first or last. We could argue that we want to know because we’re not a mainstream school, but if we’re in for a penny then in for a pound!”

Not everyone was supportive when she first brought her pupils over ten years ago; some feared disruption and others talked down to them.

“They would ask things like [she switches to a condescending tone] ‘Oh children, do you know which side that is?’ They all know! Of course they know! People’s expectations are so low sometimes. That’s why doing this is so important.”

She is motivated in her work by the premature birth of her own son, who spent the start of his life on a ventilator.

“Ever since, I’ve thought ‘this could be my son’. And if parents want their children to do things, then I think it’s our job to enable them. The world may not be ready yet, but if we can’t do it, then they’re not going to get to do it.”

If parents want their children to do things, then I think it’s our job to enable them

At the end of the first dress rehearsal, the students are happy. But Sue is unimpressed. There’s not enough stillness. Did they practice all the moves? Why were some reflective armbands facing the wrong way? The cast is sent to regroup and start again. This, we are told, is the last chance before the big day.

Among the storm troopers and stars are a number of staff members, blended to the point that it’s not always possible to tell who is a pupil and who isn’t. The school’s specialist creative arts status means it tends to attract staff with drama, dance, art and music backgrounds. Quietly they mill about moving set-pieces, daubing make-up and sorting out slippery arm-reflectors.

“We can’t do it unless everyone is on board,” says Jay as she resets the lighting board. “It’s a whole team effort and you can see my dependency on them. But on Tuesday, all this work will be worth it when you see the look on our students’ faces and they know they are performing. They can’t get an A in GCSE, but this is what they do. This is how they get to show off.”

The set is all replaced. The lights go down. It’s show-time.

A sixth-former reads the story of tonight’s tribute before Celine Dion’s ‘A mother’s prayer’ rings out, and pupils in long coats pushing prams, start interweaving rhythmically. A television set plays in the corner and Debbie Reynolds wearing a mackintosh sits a school-uniformed child with Princess Leia buns in front of it.

Three pupils suddenly burst into lip-synced song, dancing in imagined rain and twirling umbrellas.

For a moment, Matthew – a young man with Down’s syndrome, who will next year will start college – is, instead, Gene Kelly. His feet shimmying perfectly, his hat tilted at just the right angle.

It is glorious, colourful, and happy, but then the dark undertones of John Williams’ Star Wars theme begins and the stage is now filled with storm troopers. An older princess Leia has shed the uniform and is wearing white gowns. Darth Vader has left the unicorn behind. All are standing strong, sombre, still: just like Sue Jay said.

If you deprive your creative side, everything drops

It goes on, interweaving cultural references and lip-syncing, with sombre dance points, until a climax in which the children playing the celebrity stars from Hollywood’s Walk of Fame – with the stars attached to their wheelchairs – join the rest of the cast onstage, and the lights dim so that only the armbands and the fluorescent stars are visible – each light representing one of the 63 people on stage.

Lyrics to The Script’s ‘The world’s gonna know your name’ boom out: “You could be the greatest, you could be the best, you could be the KingKong banging on your chest. Do it for your

people, do it for your pride, how you ever gonna know if you never even try?” Each child, in unison, motions exactly as they had been taught. Children who don’t speak, children who can’t: all communicating.

Applause erupts and everyone is smiling. “You did me proud,” Jay tells them, “now let’s do that again next week.”

Later, in her broom cupboard-sized office, which is plastered floor to ceiling with movie posters, she explains, almost apologetically, that she has no official dance training. Educated at Haywards Heath Grammar School in Sussex, she didn’t enjoy school (“I was a borderline failing person”) but loved sport and continued turning up because it meant she could play hockey. Aiming to get a place on the England team, she went to Dartford PE College, barely went to lectures, and came out four years later with no place on the hockey side but a teaching qualification in hand.

For five years she taught at Court Lodge Comprehensive in Horley, where the children called her “bog brush” for her newly-permed hair (“It literally did look like a brush”) but she stayed mostly because the school paid for her to attend its ski trip each year. After five trips, however, she felt a new challenge was in order and took a place to teach in a special school before coming to Elizabeth II as a nursery teacher.

One day in a staff meeting the headteacher asked if anyone fancied entering the pupils for a dance festival and she said she’d give it a go. That was 20 years ago.

“Also, please don’t ask me anything about Shakespeare, I know nothing!”

What she does know is the remarkable transformation of the pupils who take part in the performances she leads.

Why would you strip a school of creative arts?

“I’ve got a particular student who is a wheelchair user. Medically, she shouldn’t be able to move her arms at all. At the end of the Rock Challenge last year, we’ve got photographs of the students and they all finished with their arms up in the air. In the photograph, she has her arm stretch up in the air. She knows we’ve finished. Medically, she can’t do that. Dance has some sort of magic.”

Seeing pupils make such progress through creative arts is why she is vicious about the government’s cuts, particularly at mainstream schools, and the way league tables are constructed, which are pushing schools to reduce time for these subjects.

“It’s so stupid. There’s so much scientific evidence if you search for it that a creative brain comes out in your maths and science. If you deprive your creative side, everything drops.

“So why would you strip a school of creative arts?” she asks. “Why do that? It’s the nice bit of school! Can you imagine going to a school with none of that?

“Obviously other subjects are important. I’m not saying they’re not but without the creative bit…” she trails off in despair.

She has one more revelation: this year’s Rock Challenge is to be her last. In July, she is leaving her job.

The turnover in teachers is immense and I’m worried that new teachers are going to be taught by pretty inexperienced young people

“It’s time to get off the hamster wheel,” she says in a subdued tone. “But I’ll be freelance. I would be very interested in going to teacher training and maybe doing something like that. Or maybe workshops for people.

“The turnover in teachers is immense and I’m worried that new teachers are going to be taught by pretty inexperienced young people, and, you know, new teachers do come to us oldies sometimes just to talk to someone more experienced. So yes, freelance workshops, I think I’d like to do that.”

Leaving the school, still covered by thunder-clapping skies, I go with a sense the golden Plato awards trophy meant a great deal to Jay and her pupils.

A few weeks later it is joined by something even more special: the Rock Challenge 2018 Perfomers’ Choice Award.

It’s a personal thing

Which animal are you most like?

There’re two sides to me. I love a lot of fun but I’m also quite strict, as you’ve seen. So whatever animal that is? Put a dog. I don’t really know. But I love dogs.

If you were invisible for the day what would you do?

I’d love to go to the Oscars. Send me to the Oscars! I love film.

What’s your favourite book?

The pillars of the Earth – I don’t know who wrote it! [It was Ken Follett – ed]. It’s amazing. It’s really thick. I love history.

Where is your favourite place?

Salzburg. I learned to ski there when I was 21 so obviously I became an expert skier and at my second special school I decided to take a group skiing to Austria. Can you imagine! We went into the building to get boots and skis and we never came out that day! I hadn’t factored in a lot of things. But by the end of the week some of them were quite good.

Your thoughts