While experts warn that internal alternative provision (IAP) in mainstream schools risks morphing into “costly” pupil “holding pens”, perpetuating cycles of exclusion, one academy trust believes it has a model for children at risk of exclusion that will allay the concerns.

A report by education charity The Difference earlier this year found more schools are using IAP – on-site support for struggling youngsters to help reintegrate them into mainstream classes – to get a grip on exclusions, absences and growing SEND needs. But it said some risk replicating the very exclusions they aim to prevent.

However, the City of London Academies Trust (CoLAT) believes the Apprenticeship Academy, based in the sixth form centre at the Highbury Grove academy in Islington, north London, is a “beacon” for what can be achieved.

Reduced exclusions

The trust’s chief executive, Mark Emmerson, said of AP: “If it could be done more effectively across the country, we’d have far fewer young people not engaged in education. That’s the big picture.”

Launched five years ago, the Apprenticeship Academy has taught dozens of children so far.

While the facility doesn’t actually offer apprenticeships, pupils are given workplace coaching or placements one day a week.

The bulk of its pupils are in years 10 and 11, but it does provide small numbers of children in key stage 3 periods of “respite” before being “reintegrated” back into their school.

“If you’ve got 18 months to get the best GCSE results you can, you’ve got to stay,” Emmerson says of keeping key stage 4 pupils in the trust. “You’ve got to stick.”

Forty-two children have “graduated successfully”, sitting their GCSEs at the end of their stint at the unit. Just one has been permanently excluded.

Figures provided by CoLAT show that, on average, attendance improved by 58 percentage points over the two years at the provision. It registered 80 per cent attendance last year, compared with a national average of 58 per cent in AP more broadly.

“We can watch them very closely,” Emmerson adds. “Whilst they’re here, they’re still on the school roll. We’ve dramatically reduced the need to use permanent exclusion.”

Who are the pupils?

Sixty per cent of the IAP students attract pupil premium funding, meaning they have been eligible for free school meals at some point in the past six years. Fifty-three per cent are on the SEND register.

Apprenticeship Academy head Rachel Halpin believes more have undiagnosed needs. There are currently 13 pupils on roll, with its year 10 cohort expected to “build up over the next couple of months”.

Children can be referred to the unit following “a really big, serious one-off incident” that could potentially result in a permanent exclusion. In such cases, they will be given the option of instead going to the Apprenticeship Academy.

Halpin will also receive a referral for pupils before “we get to the point of this completely falling off the cliff and then being permanently excluded”.

Emerson adds: “It’s really important to us that it’s actually properly an option, because we don’t want people to come here and think they’ve just been forced to come here. That’s not what it’s about.”

He also doesn’t want pupils coming to the provision “under the illusion” that it’s a “soft option”.

‘Holding pens’

All but one of the provision’s most recent 25 pupils were still in education six months after leaving. The other is considered to be not in education, employment or training (NEET).

Government figures, published in June, show 16- and 17-year-old NEET rates rose to 6.2 per cent in 2024, a 12-year high.

There is currently no data on how many schools have IAP. Unlike other specialist units, which require education, health and care plans or high-needs funding, schools are not required to report their use.

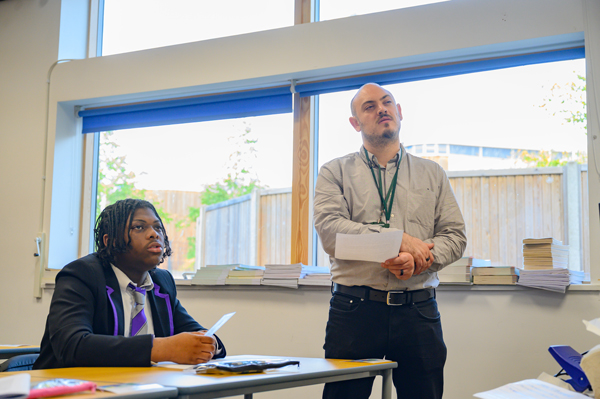

From left ThinkForward CEO Ashley McCaul and Apprenticeship Academy head Rachel Halpin

Kiran Gill, chief executive of The Difference, said many schools were developing IAPs “to help keep children thriving in the mainstream”.

However, she said these efforts were too often ”unfolding without clear guidance, and despite best intentions, some risk replicating the very exclusions they aim to prevent, creating costly holding pens rather than inclusive support”.

Handpicked teachers

But Emmerson says some of the provision described as holding pens “may not even have teachers”.

“There wouldn’t be handpicked teachers. They might have one teacher with children all day, and that’s really difficult.”

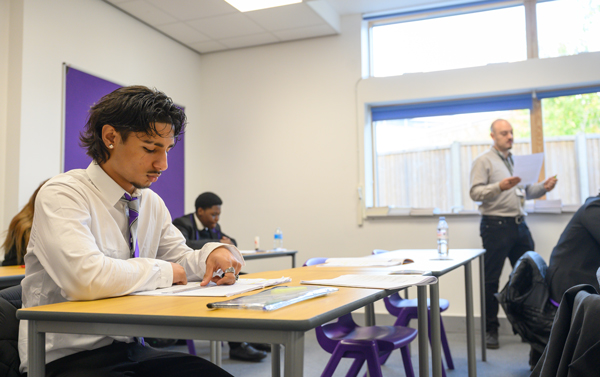

Pupils at the Apprenticeship Academy follow slimmed-down curriculums. They take English, maths and science GCSEs, as well as BTECs in business and PE.

If any of the students excel in another subject, that is added to the core offer. Those fluent in another language are often put forward to take a GCSE in that, too.

Lessons are led by Highbury Grove teachers, with timetables aligned to ensure availability.

“Where teachers are full time [in PRUs and AP], if they’re not well led and well recruited, they can be ground down. We know the teachers are coming here fresh,” Emmerson continues.

“If I look at what we’ve achieved in comparison with the children who have not wanted to take up the offer…and have opted for other alternate provision…then we see our outcomes are much better.”

Figures provided by CoLAT show 88 per cent of students improve by two or more grades in English while attending the Apprenticeship Academy. The figure stood at 66 per cent for maths.

Overall, 66 per cent secured a grade 3 or above in English. In maths, it was 44 per cent.

Work experience

Lessons are held over four days each week, with Wednesdays devoted to careers work delivered by organisation ThinkForward. Years 10s receive coaching preparing them for work, touching on areas such as CV writing and how to behave in an office environment.

The following year, their Wednesdays are spent in work placements.

“They’ll do work experience, they’ll do business mentoring, insight days, all of that,” says ThinkForward chief executive Ashley McCaul. “We’re really looking after the careers pathway piece.”

But Emmerson says it was “very difficult to get good work experience placements” for year 10s, despite people being “very supportive at the top level”.

He doesn’t “know whether they were concerned about their backgrounds or how they’d be or whether they didn’t feel confident”.

Placements have included working in the departments such as HR, facilities and procurement at the City of London’s Guildhall. Students have also worked at a recruitment consultant, a charity, local estate agency, advertising firm and even the Barbican arts centre.

Halpin is “constantly reaching out, cold calling businesses to get more people on board”.

‘High status’

According to The Difference’s IAP best practice guidance, published today, the units should not be seen as a place to “fix” the child, and real success is more likely if provision is underpinned by “strong whole-school inclusion”.

It outlined four key tenets of effective IAP: that provision is “unified” with the mainstream school, it identifies and balances learning and wellbeing, and is “shaped by measurable pupil outcomes”.

Emmerson says his aim was for the Apprenticeship Academy to be “unashamedly academic and unashamedly work focused”. He has found that when students are “on work experience, all of the children step up in an adult environment”.

The facility – which has a capacity of 20 children – occupies three rooms in the school’s sixth-form centre.

Emmerson says one of the academy’s “key principles” is “the quality of the facilities”. It’s not a “prefab, onsite cabin, which is often the case in AP – it’s high status”.

The youngsters also follow the same rules as those attending Highbury Grove.

After-school detentions are issued for lateness, and children have to wear school uniforms.

This ensures there is “no lowering of expectations”, Emmerson explains, and that students aren’t under the illusion “they are in a lesser place”.

The Difference recommended IAPs be seen as “a place of support not sanction” which balance academic progress and wellbeing, rather than a “fluffy place” where no serious learning takes place.

The charity also urged schools to try and dispel the notion that IAP is a last chance saloon before exclusion, or a place for “naughty children”.

Could others follow suit?

Isos Partnership research from 2018 revealed the average cost of an AP placement – which are largely funded through authority high-needs budgets – was £18,000 a year.

Much of this is paid for by the excluding school.

The Apprenticeship Academy receives £160,000 a year from the trust’s schools. The amount is matched by the City of London Corporation, CoLAT’s sponsor.

“If you think about the costs of normal AP, in order to be effective they have to create a space, they have to have a head, a school keeper, they have to have separate catering. They have to have all of those fixed costs,” says Emmerson.

“I don’t see why a six- or seven-school model couldn’t work [elsewhere],” he said, adding the children have “continuity, standards they understand, approaches they understand and quality teaching”.

Your thoughts