Imagine it’s Monday morning and you are suddenly told you must take a supply lesson. Your teaching subject is geography. Today, however, you will be teaching Urdu. For the few readers among you who speak the language, this may be an exciting moment. For everyone else, it is terrifying. I say this as someone who, on more than one occasion, was dispatched to try to teach a language that I didn’t even realise reads in the opposite direction to English on the page.

Although this is an extreme case of discomfort, a recent Teacher Tapp survey found that one in seven teachers currently has a timetable where more than 80% of their lessons are in subjects not studied during their degree or A-levels (or other post-16 education). If that figure extrapolates across the country, there are more than 70,000 teachers currently leading classes in subjects they haven’t studied past the age of 16.

How does this happen? Our data suggests that three secondary subjects – English, maths and humanities – are particularly prone to having teachers who didn’t study the subject post-16. For English and maths this may be due to teachers having an “aligned” degree – for example, history or engineering – in which they have used the skills of their teaching subject but didn’t study it directly. In the case of humanities, teachers of one subject are often expected to simply “pick up” any other topics in the same area. A history teacher who also does religious studies, citizenship and a bit of English may sound an exotic creature, but it’s the reality for the 13% of humanities teachers who teach subjects almost entirely outside of their specialism.

Scientists might be wondering how they have been left out given that science teachers typically work across physics, chemistry and biology, yet will often only have studied one of those subjects (if any) at university. It’s a fair cop. Scientists are more likely to teach at least some of their lessons in a topic they didn’t do after 16. But, they don’t tend to do whole timetables of off-piste topics. The majority (68%) said that at least 80% of the lessons they taught were in the subject they did at university or for A-levels.

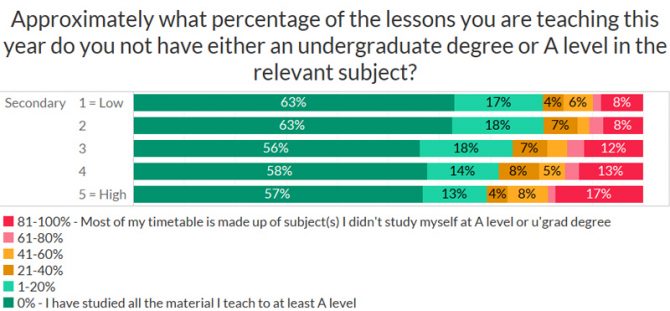

So far, so interesting. But our latest data has uncovered something perplexing. Teachers in schools with the poorest intakes are twice as likely to teach completely outside of their specialism. That is to say, if you’re a poor kid in a school with lots of other poor kids, your chance of having a teacher who didn’t study the subject they are teaching you is twice as high compared with your wealthy friend who goes to a school on the fancy side of town. Schools with wealthy intakes have 7% of staff teaching entirely outside their specialism. In poorer schools, that rockets to 17%. The difference between the two might not seem a lot, but, over a week, it’s the difference between two non-specialism lessons, and five.

Your teaching subject is geography. Today, however, you will be teaching Urdu.

But before we go getting all hysterical about inequity, we have to consider whether specialist teaching actually even matters to pupils. It’s fair to assume that a person with a maths degree has top subject knowledge. It’s not fair to assume this will make them a better teacher.

Back in 2016, FFT Education Datalab investigated whether science departments that have loads of specialist physics teachers gained higher average point scores for their pupils. The researchers used two different methods, and took into account a range of demographic and environmental factors. However, they found no relationship: having more physics teachers did not seem to increase physics results.

On the one hand, this is great news. It means we don’t have to worry that the unequal spread of teachers is affecting results. But there are other likely benefits of specialist teachers. They might have more experience of jobs in the sector, or extracurricular opportunities, or have a better understanding of the higher education space. Children in poorer schools might not be denied the opportunity to learn subjects well, but if they aren’t also given the chance to be inspired, then further knowledge in the area may never be sought. When that happens, the world is down a set of dreams, and all the poorer for it.

thanks Laura. I agree that the ability to teach well trumps subject specialist knowledge but there is a lot of global research in this area which John Howson and I looked at for the Royal Society of Chemistry a few years back. As usual generic answers are grey but some countries and states stand out for their training of specialists amongst which I would include Singapore.