The head of two failed free schools who was secretly blacklisted by the government is working with schools again after setting up a supply teacher firm.

Schools Week can reveal the government wrote to Raja Miah, the former head of two collapsed Manchester free school trusts, “strongly discouraging” him from “future involvement in schools”.

This is a national scandal that denied children a good education while a few made money. We need a full, in-depth inquiry

Lord Agnew, the academies minister, also privately ordered regional schools commissioners to blow the whistle if they found Miah, and two others linked to the trusts, “within schools in their region”.

The emergence of what seems like a secret blacklist reveals how little power the government has to ban people it deems unsuitable from involvement in education.

Miah is now behind a company that develops “meaningful partnerships” with schools by placing supply teachers in classrooms “across Greater Manchester”.

There is no suggestion of wrongdoing by Miah, who was awarded an MBE for his social integration work in 2004.

Manchester Creative Studio and Collective Spirit Free School were shut in 2018 and 2017, respectively. Rolls were falling and both had large deficits.

A government investigation, published this May, cast “significant doubts” on the legitimacy of money paid to a company connected to Miah, but concluded it was too difficult to establish a money trail. The probe looked at just two years of transactions.

Angela Rayner, the shadow education secretary, has now called for a formal inquiry after we found the two schools paid more than £2 million to multiple companies linked to Miah – despite claims from a whistleblower that the schools struggled to pay for textbooks and staff salaries.

She said the case was a “national scandal that denied children a good education while a few made money. We need a full, in-depth inquiry.”

The Education and Skills Funding Agency investigation raised concerns over whether services provided by Collective Spirit Community Trust (CSCT) – a company with links to Miah and the schools’ chair of directors Alun Morgan – were delivered and provided “at cost”.

But the government was “unable to conclude on the allegations” because of “substantial difficulties establishing any reasonable audit trail”.

Official correspondence in July from Lord Agnew, seen by Schools Week, said there had been “insufficient evidence” to formally ban Miah, Morgan and Mohib Uddin, the former chair of governors, from future involvement in schools.

However, he added the ESFA had “written directly to the three individuals, strongly discouraging their future involvement within schools.

“To provide further assurance on this, I have also written to all regional schools commissioners, requesting that they inform me directly should they become aware of any further involvement of the three named individuals within schools in their regions.”

The government now faces pressure to open an inquiry into the schools after it emerged Miah is running The Supply School.

A posting on the jobs website Indeed nine days ago shows the company, founded in June last year, was looking for someone to “focus on building relationships with our client schools”.

In August The Supply School was ordered by an employment tribunal to pay an employee almost £2,500 in unauthorised deduction of wages.

Neither Miah nor the company, where he is listed as a director with significant control, replied to a request for comment.

Rayner wrote to Gavin Williamson last month urging him to “further investigate the financial irregularities associated with the Collective Spirit Free School” adding Miah “continues to be involved in providing educational services”.

The ESFA investigation found related-party transactions between Collective Spirit Free School and CSCT in 2015-16 should have been listed as more than £500,000, rather than the £139,676 declared.

Morgan was a 50 per cent shareholder in the company, and Miah was said to have an “unclear” role, but “clear connection”. The report said Morgan had breached the Companies Act. He could not be reached for comment.

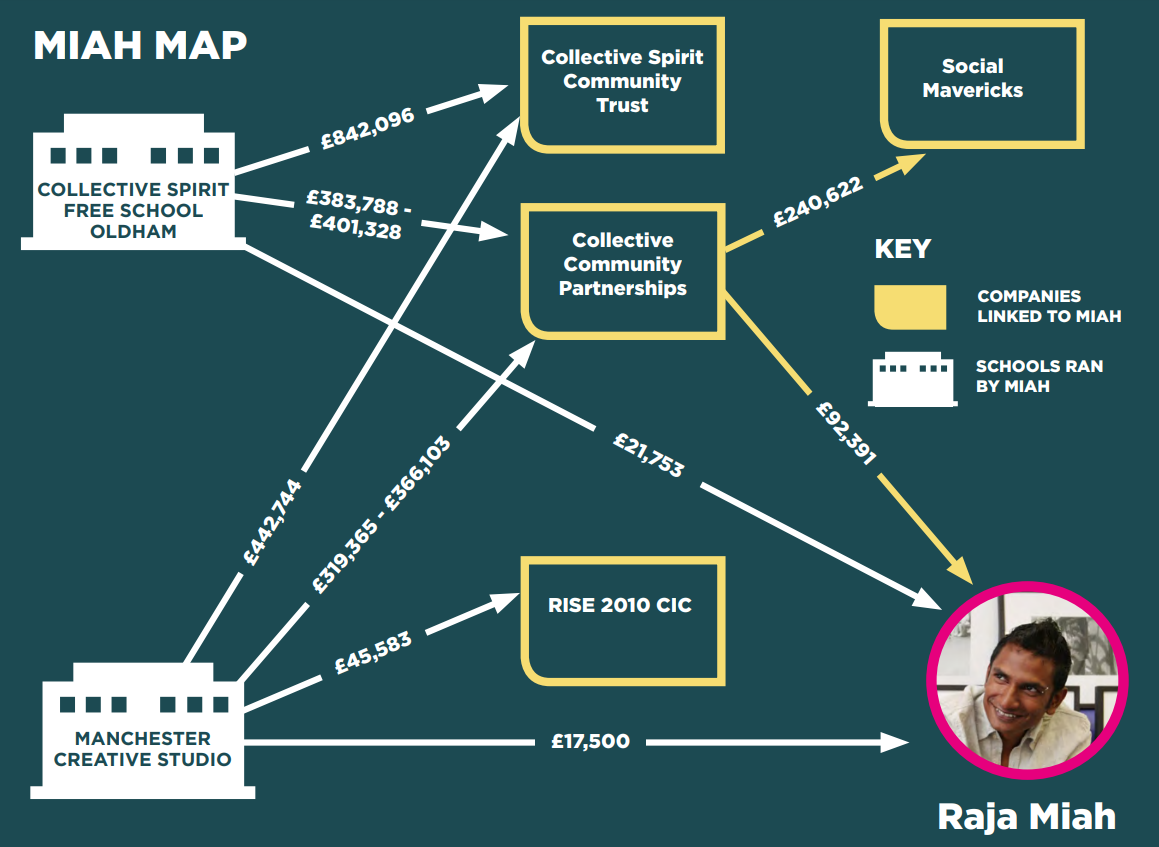

Schools Week analysis of the schools’ annual accounts show that more than £2 million was paid out to companies connected to Miah between September 2013 and August 2017.

Manchester Creative Studio paid between £825,192 and £871,930 to companies connected with Miah, or directly to Miah himself, between September 2013 and August 2017.

Collective Spirit Free School paid between £1,247,637 and £1,265,177 in the same period.

Lucy Powell, the local MP and a former shadow education secretary, called for a “full and completely independent investigation into all the related-party transactions” at the schools.

“It is not good enough that ministers and the ESFA have seemingly washed their hands of this case, and put it in the ‘too difficult to resolve’ pile. Public trust and the integrity of our school system is at stake.”

As well as CSCT, companies receiving payment included Collective Community Partnerships, where Miah was listed as director until it was dissolved in 2016, and Rise 2010 CIC, which listed Miah and Morgan as directors before it was dissolved in 2013.

Collective Community Partnerships received more than £700,000 from the two schools, but also paid £92,391 to Miah directly, as well as £240,622 to a company called Social Mavericks, which listed Miah as its only officer.

Although Miah stepped down as director of both trusts in September 2014, the ESFA found he was still listed as a director in October 2016 board minutes, as chief executive in financial statements during 2015-16 and that he was involved in discussions with the regional schools commissioner’s office until January 2017.

The Manchester schools closed after damning Ofsted reports warned of widespread failings in education, safeguarding and provision.

The Department for Education gave Collective Spirit more than £250,000 to help in the closure, and wrote off debts of at least £300,000 in the school’s final year.

Manchester Creative studio received more than £400,000 in emergency government funding to prop it up.

The DfE said the investigation into the schools was now closed. Uddin did not respond to request for comment.

Update, Friday November 8

In official communications, Lord Agnew said the case had been referred to the Charity Commission in July 2018 and February 2019. A spokesperson for the Charity Commission has now confirmed that the ESFA asked it to consider whether its regulatory powers “would be the most effective route to achieving charity law compliance and action against individuals in this case”.

However, she said the Commission told the ESFA in February that it would not be taking the matter forward, as the “enforcement options” available to the government would be “more effective” than the Commission using its own powers.

‘There were no cleaners, no books…no money’

A former employee at the Collective Spirit Free School has lifted the lid on missing resources, inadequate staffing and health and safety fears at the school.

The teacher, who spoke to Schools Week on the condition of anonymity, claimed teachers were left to clean their own classrooms.

“The toilets never got cleaned. It was disgraceful . . . Why were we not able to afford any books? Why were there no cupboards? The answer is because there was no money.”

Collective Spirit was rated ‘inadequate’ in May 2016. A monitoring visit that November said pupils were not allowed to bring in lunch, but the food provided was “of such poor quality that pupils often throw their lunch away or miss it” and go to lessons “hungry”.

The teacher also alleges that class sizes were increased and timetables and teaching staff reduced in an attempt to save money. He also claimed the school had one phone and no computer network.

In the 2016 Ofsted report, inspectors warned pupils were “not well prepared for the demands of key stage 4”.

Meanwhile at Manchester Creative Studio, rated ‘inadequate’ in 2017, Ofsted said pupils’ progress in maths and English was in the lowest 1 per cent nationally in 2016.

The whistleblower said: “There are children out there who have literally had their lives taken away from them. What chance have they got of getting on to a decent A-level programme when they finish their GCSEs now?”

Schools Week editorial

The sector will welcome Lord Agnew getting tough on those who have presided over failed academy projects. However news of the government secretly blacklisting people is concerning.

More than anything it exposes just how powerless the department is to regulate the academies sector.

The long-awaited investigation into the Manchester free schools identified several breaches of academy rules. But investigators were unable to reach conclusions on allegations of irregularities because they could not establish an audit trail of the cash flowing from the schools to firms linked to leaders.

There was not enough evidence of misconduct to officially bar the individuals involved from running schools.

Nonetheless Agnew clearly deemed them unsuitable, and has written to his regional schools commissioners asking them to blow the whistle should they find them working in schools (cartoon below). Is this right?

Surely the government should instead ensure that it has the expertise to investigate properly when academies fail. This will ensure that taxpayers get to know the truth and appropriate action is taken.

This is why we need governance regulation.

Cases should be referred, decided and if appropriate people ‘struck off’.

We do have regulations in place. The problem is that people in general, and unfortunately maybe the author of this article, don’t really understand how this all works.

Individuals can be banned from being company directors and/or charitable trustees, either of which would mean they couldn’t be a director/trustee of an academy trust. This is a very serious course of legal action and would require substantial amounts of evidence which, given the nature of these situations, is often hard to find. Formal legal proceedings are therefore not very common. This has nothing to do with the DfE or Government as this applies just as much outside the education/public sector.

However the DfE also has the power, sometimes directly sometimes indirectly, to stop/remove an individual being a director/trustee or a member of an academy trust. This is a contractual right, under either the Articles of Association or a funding agreement, and does not require the same level of ‘proof’. This is presumably why DfE and RSCs have ‘blacklists’, or if we’re being less hyperbolic and sensationalist they probably have lists of ‘people of concern’ that if their name pops up the relevant individual knows they should probably dig a little deeper.

But this story doesn’t seem to be about governance. From what I read above Mr Miah has set up a business, and is selling services into schools. It would be worrying times if the Government could force any body, be it school, academy trust, Council, or private company, from contracting with a legitimate business. Should a light be shone on Mr Miah and all his previous history so that schools know who they’d be getting involved with – absolutely. But you’d be on very shaky legal ground from banning them from dealing with his business as long as it’s legitimate, even if he was proved to have been fraudulent in the past.

His prior record, and what did or did not happen at CSCT and the two free schools, are an entirely separate issue. They should absolutely be scrutinised with a powerful microscope and, if wrongdoing is identified, the guilty parties should be pursued, punished, and force to repay the relevant monies. There should be no hiding place, and no failure to investigate.

It’s time for forfeiture of the MBE? Best get the message out to: honours@cabinetoffice.gov.uk

He and his cronies are still at it see his name is with the THE SUPPLY SCHOOL LTD his name is on it .

Rather disturbing really.