Schools Week is exploring the way vulnerable groups of learners have fared under the coalition. In the third of a five-part series, John Dickens looks at who exactly is benefiting as schools receive more than £6bn of pupil premium funding and questions if is really closing the attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and their wealthier peers

The coalition government ushered in its flagship pupil premium policy in April 2011 with a £625 million war-chest to “provide a real incentive for good schools to take pupils from poorer backgrounds”.

That commitment has increased annually to a whopping £2.5 billion this year to help to raise the attainment of disadvantaged pupils and to bridge the gap with their peers.

School leaders have welcomed the extra cash and it’s a policy supported by many politicians in other parties.

But has the huge investment closed the attainment gap?

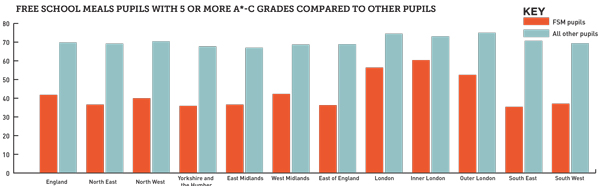

It depends who you ask. The gap at GCSE between pupils who qualify for free school meals (FSMs) [and receive the pupil premium] and all other pupils looks to have widened. The gap between FSM pupils who achieved at least five A*-Cs, including English and maths, and all other pupils has risen in recent years from 26.4 per cent in 2011-12, to 26.7 per cent in 2012-13 and to 27 per cent last year.

The Department for Education (DfE) changed its methodology last year for the calculation of key stage 4 performance measure data, to factor in the removal of vocational qualifications from the league tables and to only count a pupil’s first entry to an exam. Using previous calculations, without adjusting for these factors, the 2013-14 gap would actually be 27.2 per cent.

The DfE says there is a proposed new index to investigate how the gap can be measured across the whole attainment range in light of the assessment reforms.

Sir John Dunford, the national pupil premium champion, said the above figures are not a reliable year-on-year indicator because of policy changes. He insists the gap is closing.

The government’s view is that there has been “significant progress”, pointing to 69.3 per cent of disadvantaged pupils now meeting the expected level in both reading and maths at the end of primary school, compared with 62.2 per cent in 2011.

Overall there doesn’t seem to be a straightforward answer. But new research seen by Schools Week paints a clearer picture.

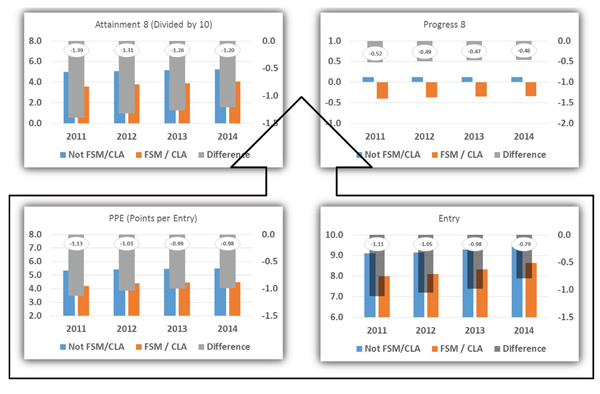

Education Datalab has investigated the trends in attainment from 2011 to 2014 by using a prototype of the new Attainment 8 and Progress 8 measures, which will be introduced into performance tables next year.

Dave Thomson, chief statistician, said: “The attainment gap is closing, albeit slowly, if you look at an indicator that covers the full ability range, such as Attainment 8, rather than just the C/D borderline.”

He said most of the improvement is driven by disadvantaged pupils entering more of the qualifications that count under Attainment 8. At the current rate, disadvantaged pupils will not catch up with other pupils until 2035 (the year that David Beckham turns 60).

Deeper examination also shows that based on the average grade per entry, the GCSE achievement gap widened or remained static from 2013 to 2014 for all pupil premium children – except those with high prior attainment.

Sir John said: “There is still a long way to go before the achievement gap is closed, but some schools have shown that it is possible — and this is acting as a spur to others to raise attainment of disadvantaged pupils.”

The annual Pupil Premium awards, run by the DfE, are full of success stories. Millfield Science and Performing Arts College, in Thornton-Cleveleys, Lancashire, won the secondary award in 2014.

Seventy-three per cent of disadvantaged pupils achieved at least five A*-Cs at GCSE, including English and maths, compared with 76 per cent of other pupils. The proportion of disadvantaged pupils making expected progress between key stages 2 and 4 was 96 per cent, compared with 92 per cent for their peers.

Sir John added: “As well as providing schools with additional funding, the pupil premium policy has sent out a vitally important message: disadvantaged children can achieve. Schools have responded to this in a very positive way.”

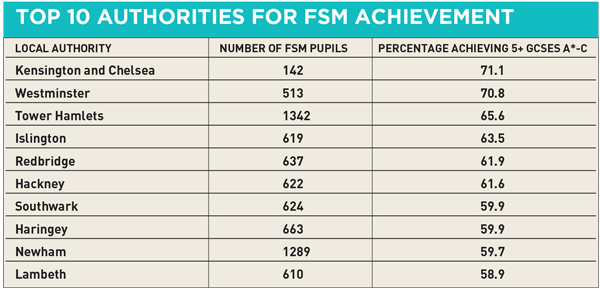

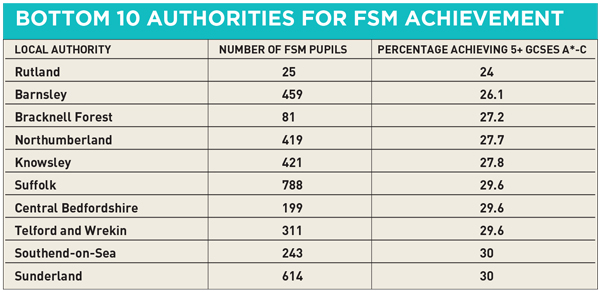

But DfE figures, released in January, show there are big variations across the country. While 46.5 per cent of FSM pupils in London achieved five or more A*-Cs including English and maths last year, only 28.4 per cent of pupils achieved the benchmark in Yorkshire and Humber.

A report released by cross-party think tank Demos in January says London continues to “prop up” the national figures, with the attainment gap widening from 27 per cent to 29.5 per cent if they are excluded.

Ian Wybron, an education specialist at Demos, told Schools Week: “It’s concerning that despite this injection of cash it is not yet getting the results.

“But it will take time to bed in and you will see the biggest results with pupils who have had this funding year on year. It’s a matter of time and schools sharing knowledge.”

After its pupil premium success, Millfield won £10,000 to support five local schools looking at the impact of pupil premium. It also hosted a best practice training day.

This sharing of best practice could be vital to driving up attainment elsewhere. Marianne Pope, researcher at schools information and advice service The Key, said: “Schools need clarity on what will be considered an acceptable use of the [pupil premium] grant and what won’t.

“Many of the school leaders I’ve spoken to have said they want more guidance on what the most effective ways of spending the premium are so they can get it right.”

When the scheme started, Ofsted found that schools spent too much on teaching assistants and school trips without evidence of the impact on attainment.

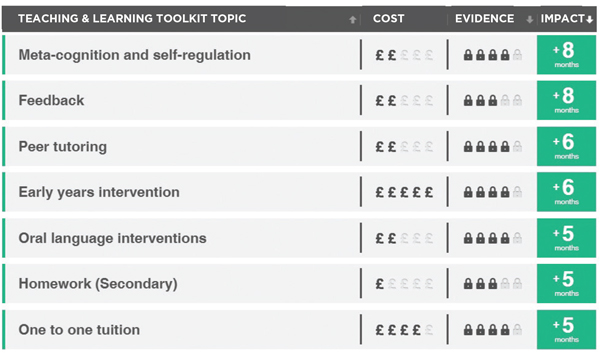

But Sir John says schools are now increasingly using the Education Endowment Foundation’s toolkit and evidence to influence how they use their cash. “As well as improving the attainment of pupil premium pupils, there are some heartwarming stories of the way in which schools have used pupil premium to turn around the life chances of disadvantaged children.

“Because disadvantaged young people are often held back by a lack of aspiration from their parents who have failed to engage with their educational progress, schools have used the pupil premium in some imaginative ways – such as literacy classes for parents – to increase parental engagement.”

But the introduction of the universal infant free school meal policy last year has had a knock-on for pupil premium. Fewer parents are reportedly applying for FSM with some schools having to offer incentives to encourage sign-up so they don’t lose out on pupil premium funds.

So what does the future hold? Schools minister David Laws announced an extra £22.5m funding for 2015-16, which will include early years providers for the first time.

Beyond that, it is a decision for the new government. But Sir John remains positive. “The statistics are moving in the right direction,” he says. “Schools around the country have a much more rigorous approach to using pupil premium, which should lead to an acceleration in the improvement.”

Data showing the attainment gap converted into Progress 8 and Attainment 8 from Education Datalab’s “Disadvantaged Pupils” report

Sir John’s Five Pupil Premium Successes

1 The attainment of disadvantaged pupils has risen

2 It has drawn attention to the size of the attainment gap in England and schools have responded in a very determined way, recognising that 100 per cent buy-in from their staff is a vital precursor to success

3 Many schools have done inspiring work and other schools have been prepared to look to them for ideas and methods

4 The most successful schools monitor pupil progress frequently and put interventions in place quickly when pupils need extra support

5 High quality teaching must be an essential component of every school’s pupil premium policy, with those pupils getting the best teachers

A DfE spokesperson said: “The pupil premium has been a crucial intervention and, in the hands of outstanding teachers across the country, is already making a real difference to children’s lives.

“Disadvantaged primary children achieved their best ever results this year, and the real attainment gap is narrowing at both primary level and secondary level.

“At secondary level pupils have benefited from the pupil premium for a much smaller proportion of their schooling, but the gap narrowed again there too when Wolf reforms and other changes are taken into account.

“Teachers and school leaders deserve credit and recognition for their tireless efforts to give every child the fair start in life they deserve.”

the pupil premium is a cheap way to fund a high quality education system.

It was a gimmic to appear to do something positive for disadvantaged pupils.

The pupils in receipt of FSM are a complex group. It contains many migrants who can make considerable progress when the language barrier is overcome. It contains children who’ ability is limited and who despite fulfilling their potential, will not progress to higher levels.

The poor attainment of pupils from deprived backgrounds has complex reasons.

The system is working, dare I say, in a way that their ability in later years is being determined from tests, and the resulting follow up by schools, carried out a a very young age. There is too much testing!!!!!!!! It is having effects that are not intended. It iis very middle class.

The final point is that these performance tables replicate funding tables very closely. There must be a high correlation between funding and performance. If schools were properly funded then pupil premium would not be required .