Phonics has a “dramatic impact” on the accuracy of reading aloud and comprehension, researchers have claimed.

A study, published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General today, tested whether learning to read by sounding out words (as done in phonics) is more effective than focusing on whole-word meanings.

Researchers from the Royal Holloway, University of London and the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit trained adults to read in a new language, printed in unfamiliar symbols, and then measured their learning with reading tests and brain scans.

The results were striking

When the training emphasised phonic knowledge, participants reached a “high-level” in reading aloud (more than 90 per cent correct answers) by day five, compared to day 10 for those trained using meaning-based cues.

Professor Kathy Rastle, from the department of psychology at Royal Holloway, said: “The results were striking; people who had focused on the meanings of the new words were much less accurate in reading aloud and comprehension than those who had used phonics, and our MRI scans revealed that their brains had to work harder to decipher what they were reading”.

However some academies have questioned the study – claiming it does not measure “true reading”.

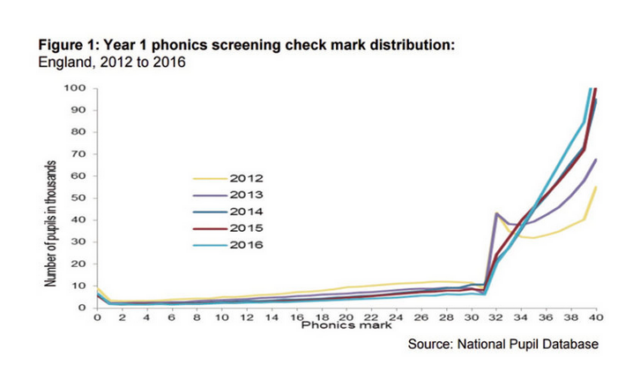

Phonics checks were introduced by the government for year 1 pupils in 2012. The number of pupils reaching the expected standard in the checks has since risen from 58 per cent, to 81 per cent in 2016.

There are concerns over the reliability of the teacher-assessed checks – mark distribution data shows a large spike in pupils attaining the pass mark (last year was the first time teachers were not told the pass mark prior to the test – resulting in a less severe spike, see image right).

Previous research into the effectiveness of phonics also hasn’t all been positive. A report by the London School of Economics found the phonics method had a large effect at the age of 5 and 7, but “no measureable effect on pupils’ reading scores at age 11”.

However the study, which involved phonics consultants being sent to help teachers, did find that phonics had “persistent effects” on pupils eligible for free school meals and those where English isn’t their first language.

There have also been objections to the use of “systematic” phonics, said Rastle, with some in the education community arguing for a variety of phonics and meaning-based skills.

But she said her research showed reading instruction that focuses on teaching the relationship between spelling and sound is the “most effective”.

Research doesn’t measure ‘true reading’

However Dr Andrew Davis, honorary research fellow at Durham University’s School of Education, questioned the research on several fronts.

He said the tests presented text items in isolation, adding: “Since true reading often needs to make use of context to interpret word meaning, (or even which word is being encountered), the tests arguably aren’t testing reading proper.”

He also questioned whether the artificial language used, for example, any heteronyms (a word spelled identically but with different sounds and meanings).

“Often, the reader cannot work out which word he/she is dealing with without looking at the context – often the meanings – of other words in the relevant sentence. This interactive process seems to have been ruled out by the very way the research was set up.”

But researcher Dr Jo Taylor, from the department of psychology at Royal Holloway, said her paper shot down suggestions phonics “disadvantages reading comprehension”.

“Phonics actually enables reading comprehension by relating visual symbols to spoken language. The laboratory method that we’ve developed in this study offers strong evidence for the effectiveness of phonics, and has also helped us to understand why phonics works, in terms of the brain systems responsible for reading”.

Researchers will continue the work by investigating how reading expertise develops in the brain.

Nick Gibb, the schools minister, says the research highlights the potential benefits of learning to decode using phonics.

“Thanks to the hard work of teachers, our continued focus on raising standards and our increased emphasis on phonics?, there are now 147,000 more six-year-olds on track to becoming fluent readers than in 2012.”

The research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council.

Interesting. I don’t doubt for a moment that using phonics as part of a wide strategy that also develops children’s love of books, vocabulary and cultural capital is vital. But did the ‘new language’ the researchers invent use an alphabetic code as complex as the English language system with an equivalent vocabulary including homophones?

It wasn’t fully a language. 24 adults learned symbols for 48 ‘words’, half with pictures, half without – words for nouns that they would recognise. They did this over a few days. I wonder whether they still know them?

This is a poster made by the researchers:

https://media.wix.com/ugd/bcf054_b6ab99a17289400ca25b5337af465ad2.pdf

The researchers also seem to say it is preferable for children to engage less brain than more on a reading activity because using more brain means it’s harder? I am dubious about that.

I can decode Spanish and German but I’m likely not to have a clue about the meaning unless it’s very simple.

That’s not to say phonics isn’t valuable. Accumulated evidence shows systematic teaching of phonics is the best way of teaching children to read. But, and this is crucial, it should be combined with a full programme of language development. DfE commissioned research in 2014 found teachers were combining phonics with other methods. Gibb ignores this. http://www.localschoolsnetwork.org.uk/2014/09/gibb-claims-rise-in-number-passing-screening-test-is-down-to-relentless-emphasis-on-phonics-but-dfe-commissioned-research-contradicts-this

I watched BBC Four’s ‘B for Books’ (still available here http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07jlzb7). It showed children being introduced to phonics. But I also saw a teacher asking one boy to look at a picture accompanying the text to decide what was written (this ‘cueing’ is frowned upon by phonics purists). It was something like ‘the cat is on the table’. Each consecutive page had the same text but with a different item on the table. The boy, Stephan, realised the pattern (rather wearily) but I’m not sure he was ‘reading’. He declared it was ‘boring’. But by the end of the year he was decoding well.

I’m not leaping to any conclusion here. It would be necessary to follow Stephan minutely to know what methods were used. It would be more difficult, however, to decide which were most helpful and which, if any, hindered his progress.