Heads who taught PE or RE before leading failing academies are more likely to adopt a damaging “short-termist” approach to running schools, but are awarded the most honours.

A major study by the Centre for High Performance has identified the impact of different “types” of headteacher – with their leadership style linked to their degree subject for the first time.

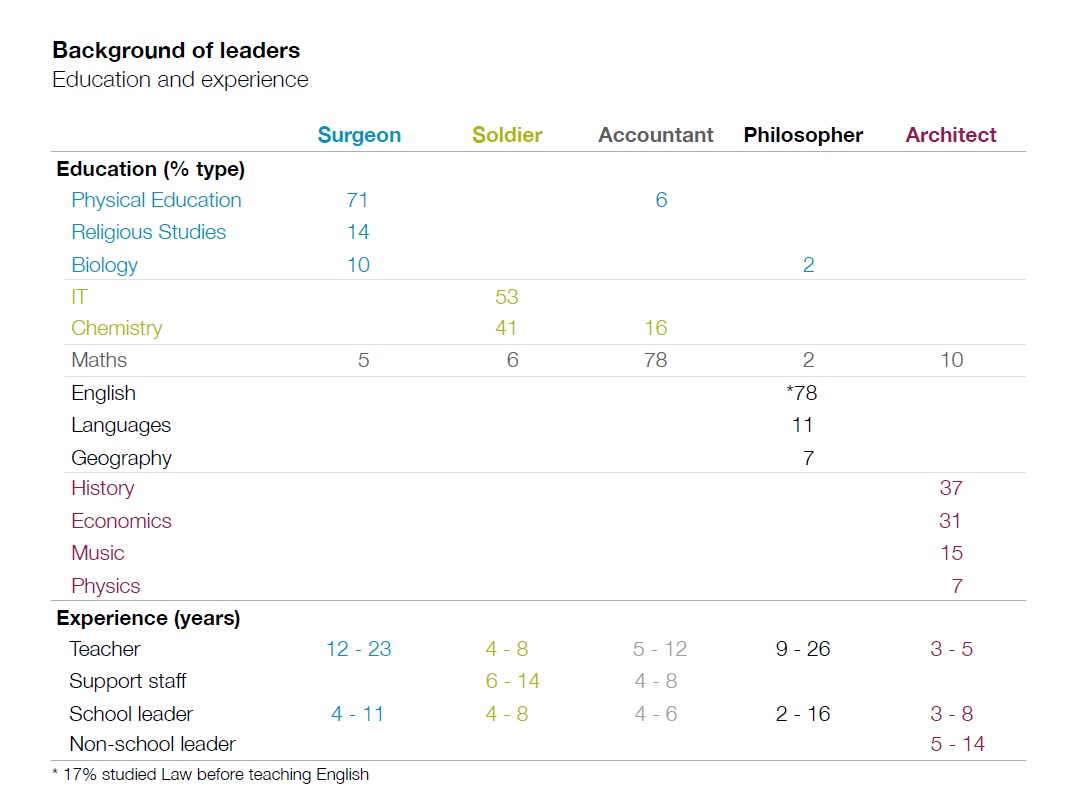

Researchers Ben Laker and Alex Hill analysed the impact of 411 secondary heads in turnaround academies, using interviews, grades, budgets and management information system data across a seven-year period up to 2015 to uncover five headteacher “types”: the philosopher, the surgeon, the architect, the soldier and the accountant.

In what education experts have called a “groundbreaking” analysis of data, the tiny but influential group of “surgeons”, who mostly taught PE or RE before heading up struggling schools, adopted a damaging “short-termist” approach that nevertheless saw them disproportionately awarded damehoods and knighthoods.

Schools Week had exclusive access to detailed figures linking headteacher “styles” to their teaching subject

Hill said this type of head “mostly grows results quickly by kicking out low-performing pupils.

“They would lose as many as 25 per cent of [pupils in] the GCSE year, so the percentage taking A* to C rockets. These heads believe in good and bad students. But it’s not real improvement, and when they leave everything falls apart,” he said.

“At present they are being held up as examples of good practice. They have power within the system.”

The research has been released in a Harvard Business Review article, also co-authored by Liz Mellon and Jules Goddard, but Schools Week had exclusive access to more detailed figures linking headteacher “styles” to their teaching subject.

The “surgeons”, of which 71 per cent were PE teachers and 14 per cent RE teachers, were paid an average of £150,000 a year and were most likely to want a higher salary – yet cost a school about £2 million in consultancy fees to fix problems once they departed.

And they were the only type of leader in those surveyed to hold damehoods or knighthoods, as well as being the most likely to have political sway.

While “surgeons” had the most damaging impact, they made up only 8 per cent of the heads surveyed (33 out of 411).

The majority of heads surveyed were “philosophers” (51 per cent) – mostly former English literature teachers with no experience outside education – who saw their role as enablers of better teaching rather than prioritising staff management, revenue and better working environments.

“Philosophers talk an amazing game, they believe teaching can solve the world, but they don’t do anything. Those schools coast or decline,” said Hill.

“If this is the majority of the people in the system, engaging with them about leadership won’t work, because they don’t talk about it.”

Languages teachers also featured in the philosopher group, along with geographers.

The highest-performing heads over the longer term, whom the report labelled “architects”, were mostly history and economics teachers, although music and physics teachers also fit into this group.

This group created a budget surplus and saw pupil grades improved, even once their tenure ended. Some 86 per cent of these had experiences outside education before teaching.

“Architects” did not produce improved GCSE results in the first three years (results improved long term), focusing instead on relationships with the community and provision for underperforming students, yet they were paid about £86,000 a year and had the fewest CBEs, OBEs or MBEs of any group.

James Toop, chief executive of Teaching Leaders and the Future Leaders Trust, said the “groundbreaking” research was the first to tie leadership types with school performance over a full time period.

“There’s a broader question about how we use rewards recognition within education. It shouldn’t be the ones who shout loudest that get noticed.”

Better leadership training would also prevent UK heads from falling back on beliefs about leadership based on their chosen teaching subject.

Hill said: “We decided to see if there was a pattern between leadership types and their subject. And it’s not just a pattern, it’s completely clear.

“Maybe the subject you chose to study is a measure of other factors – how you grew up and what you believe. With teachers there’s usually no external influence from other sectors. So you fall back on the subject. If you’re a PE teacher, for example, it’s about winners and losers.”

By moving to performance measures that took into account how many pupils had been excluded, the “surgeon-type” of leadership would soon be exposed, the report claims.

Laker and Hill have previously called for the government to re-think its measurement systems to encourage a longer-term approach from superheads.

Dan Belcher, senior education lead at the Students, Schools and Teachers Network and a former assistant principal, said short-termist leadership in particular needed to go.

“I do wonder whether there is a question of a leadership crisis. Leadership is critical – it can act as a buffer between policy and how it is implemented in schools.

“The most important thing for me here is the legacy aspect. We need to look at Ofsted accountability and think carefully about short-termist behaviours that may be encouraged.”

Updated to correct the percentage of excluded pupils from 75 per cent to 25 per cent. In some cases 25 per cent of pupils are excluded, leaving just 75 per cent of the cohort at the school.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

I think its interesting that those who talk a good game get to be heads in the first place – but sometimes its just all talk. Scientists like to get right to facts -and that is not well recognised in our society. But kids might appreciate that !

I found these data a bit confusing:

411 headteachers in sample; 33 of whom were ‘surgeons’; 71% of whom had a PE and 14% an RE background.

Doesn’t this imply 23.43 PE heads and 4.62 RE heads were surgeons?

If PE were 70% of surgeons = 23.1 heads; If PE were 72% surgeons = 23.76 heads. Like wise, for RE 13% = 4.29; 15% = 4.95. – so this doesn’t appear to be an issue of rounding up or down for simplicity of reporting.

Is the original data publicly available somewhere?

Another article that makes sweeping generalisations about PE teachers. Why make reference to the subject when talking about leadership styles? I’m sure there are many ‘surgeons’ from cross the curriculum.

Just another article implying that PE teachers are somewhat lesser than other teachers.

Mmmmmmm… to teach PE well, you need good powers of analysis and to communicate well with people. I can’t see any reason why good PE specialists can’t be philosophers as well.

An insisdious little article….so we should be appointing more ” Architects” should we, what, to ‘improve profits’ whilst claiming the community benefits?

Far too much is being made of this ONE study. It might be newsworthy but is it education-worthy? I’m not so sure

The study merely confirmed what a lot of teachers have seen at first hand. The superhead who arrives promising the earth, stays two to three years and then moves on at a higher salary. By which time, a lot of experienced and decent staff have left, the pressure to work 12-16 hour days being too much, and Ofsted have decided to visit owing to the high nyumber of exclusions, just in time for some new head to get it in the neck, and be harried until THEY leave. In all cases, it is the children who suffer, even those who get the grades that help the school show improvement – it is at the expense of their mental health, and they can’t keep it up later. Nor should they have to – this is not education; it is short termism and a waste of human resources and money.

Patching up and having to catch up in education is one of the problems of an inefficient, ineffective earlier education system, and now based on a 19th Century exam production line is certainly costly. Children are not products to be turned out all the same,mtheyndo not start the same they are unique and all children have some kind of special need,mwith some more than others.

How about looking at spending more of the high salaries and wasted intervention strategies mentioned, to have smaller classes in primary schools, (reason for many choosing fee paying schools) to ensure more youngsters acquire the basics through a more individual approach – surely someone somewhere can acknowledge that if one person has to plan, mark, assess for further learning and provide support for a group of 15, instead of 35 now the primary norm, that much more will happen?