A worrying lack of up-to-date guidance on how to ensure pregnant pupils continue their education is fuelling a rise in the use of alternative provision for those expecting a baby.

The government claims five-year-old advice on how to deal with pupils with “health needs” – which makes no specific mention of pregnancy – is good enough to help schools navigate the tricky issue.

But school leaders say it needs updating, along with improved support services for pregnant pupils.

Pressed on the matter earlier this month, Lord Agnew, the academies minister, pointed to 2013 guidance for local authorities on “Ensuring a good education for children who cannot attend school because of health needs”.

The guidance tells local authorities that they must “arrange suitable full-time education (or as much education as the child’s health condition allows) for children of compulsory school age who, because of illness, would otherwise not receive suitable education”.

But one local authority officer told Schools Week that their council, in an area of the north of England with historically high teenage pregnancy rates, “doesn’t even bother” with the 2013 guidance because “it makes such a small reference to the issue of pregnancy, which is rarely a health issue anyway ”.

Instead, the council in question uses “Guidance on the education of school age parents”, published back in 2001, alongside the 2010 Equality Act, to remind schools “that they do actually have a legal responsibility to continue to offer a young woman an education that is suitable for her while she’s pregnant and then once she has had a baby”.

The source, who wanted to remain anonymous, also suggested that lumping pregnant pupils together with children with serious health problems, as the 2013 guidance does, may make their ongoing education more complicated, by enabling schools to say that having a pregnant child onsite creates a health and safety risk.

“Schools try to justify removing these pupils on health and safety grounds and we don’t want to give them any more reason to try to use that excuse,” they said.

If people haven’t got the resources, there is no mandate for them to put particular provision in place

In an answer to a written question, Agnew insisted it was up to councils to find provision for children who are unable to attend “school because of a health condition or any other condition, for example pregnancy”.

However, he admitted the department has not consulted on the issue in the past five years.

Baroness Tonge, vice-chair of the all-party parliamentary group on sexual and reproductive health, who questioned Agnew earlier this month, said the situation was “really very worrying”.

“I think this whole thing needs looking at,” she told Schools Week.

“It sounds to me that it depends on individual schools as to what arrangements they make. Many schools are no longer managed by local authorities, and set their own agendas.”

Alison Hadley, director of the Teenage Pregnancy Knowledge Exchange at the University of Bedfordshire and a teenage pregnancy advisor to Public Health England, led the implementation of the Labour government’s 10-year Teenage Pregnancy Strategy for England from 1999.

She said provision for supporting young parents to continue education has “lost its focus” and become “disparate” as the rate of teenage pregnancy has dropped across the country.

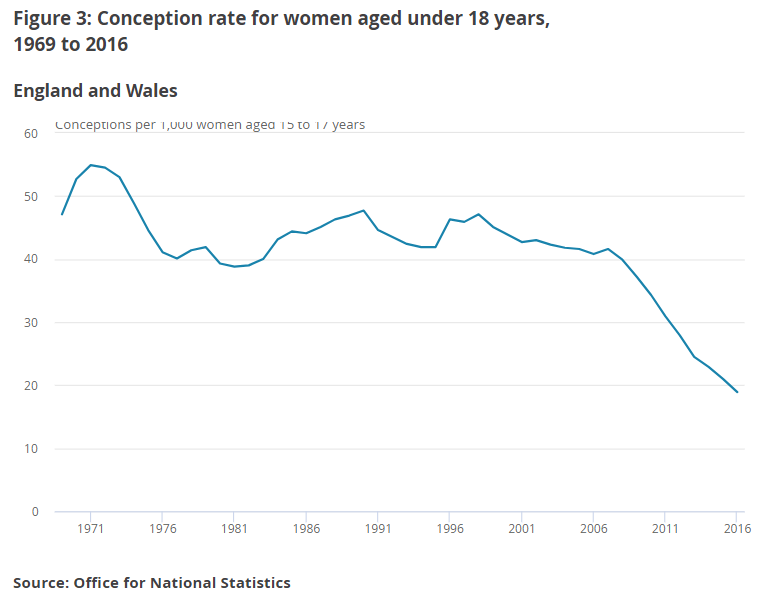

Conception rates for women under 18 years in England and Wales hit a record low in 2016, having fallen by 60 per cent since 1998, according to the Office of National Statistics.

“If people haven’t got the resources, there is no mandate for them to put particular provision in place, which is why having some updated guidance would be really helpful,” she said. “The 2013 guidance wasn’t clear enough.

Sarah Hannafin, senior policy advisor for school leaders’ union NAHT, said support has “become less available as all services struggle with budget cuts”.

“Up-to-date guidance is needed that reflects the current systems to help education, health and social care work together to support young parents,” she said.

Ros McMullen, the executive principal of the Midland Academies Trust, believes a “practical approach” is the best way for schools to support pregnant teenagers and young mothers.

“Young people who are facing difficulties need to be supported properly, but they don’t need to be indulged. It’s about supporting these young women to find their way out of poverty and aspire to be more than just teenage mums.”

Kiran Gill, chief executive and founder of The Difference, an organisation that aims to get more teachers working in

alternative provision, explained that a well-resourced AP environment can be a very positive place for a pupil who is continuing to learn while expecting a baby.

But she said the AP sector needs more teachers.

“The ratios of child to adult in pupil referral units and alternative provision schools mean that really deep and supportive relationships can be built – so crucial when you’re going through a massive and scary life event like a pregnancy,” Gill said.

A DfE spokesperson told Schools Week the government believes the 2013 guidance is still relevant and adequate for informing schools how to ensure pregnant pupils can continue their learning. She added that the guidance will be kept under review.

Your thoughts