One of the coalition’s major engines to improve teacher training retention will not help many of the schools most in need because their efforts are concentrated in predominately wealthy areas, Schools Week can reveal.

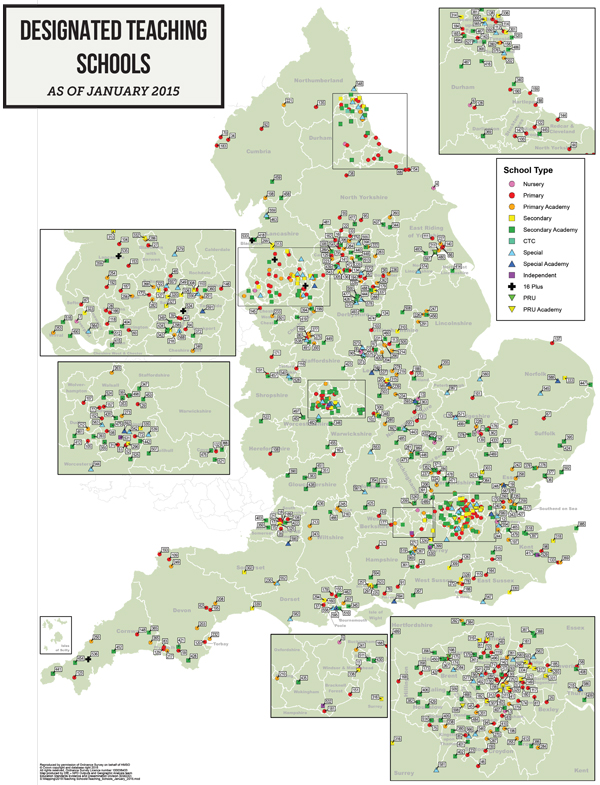

Analysis conducted with the help of Education Datalab reveals that only two of the 563 teaching schools – outstanding schools that work with others to provide high-quality training and development – are in areas that serve the 25 per cent most deprived populations.

Just 10 per cent are in areas serving the poorest half of the population.

The figures suggest that the teaching schools programme will not address concerns outlined by Sir Michael Wilshaw, chief inspector, about policies designed to improve teacher recruitment, particularly in coastal, isolated and deprived areas.

Speaking at the Festival of Education at Wellington College last week, he said that the distribution of new teacher training was “skewed towards those areas that already have good training provision and a high proportion of good schools”.

He said this was because current rules stipulated that only outstanding schools could lead school-led training, and that these tended to be the “more advantaged schools”.

In the east of England, he said the “vast majority” of the 70 or so teaching schools were “in the affluent areas of Cambridgeshire, East Hertfordshire and South Essex – very few are in the isolated rural and coastal parts of Suffolk and Norfolk”.

The problem was having a knock-on effect as emerging evidence from a review of teacher recruitment in the east, south east and north west of England showed that networks of schools approved to run school-centred teacher training courses (SCITTs) were more able to recruit than those that were not.

Furthermore, the hope that teaching schools would act as hubs supporting other local schools was not being realised. Nearly three-quarters of heads spoken to in the most disadvantaged schools said they struggled to get good staff. Support was not always forthcoming, “even where there is school-led training nearby”.

Sir Michael said that one head in a school deemed to “require improvement” spoke of having little contact from the local teaching schools. “He also believed the schools where they trained usually snapped up most trainees.”

But the chair of the Teaching Schools Council, Vicky Beer, told Schools Week that the postcodes of teaching schools “do not give a particularly representative picture of where the work takes place, because of the fluid nature of the (teaching school) partnerships”.

She also noted that “teaching schools have never been posited as the only solution” to these long-standing problems.

She said the number of teaching schools in areas such as Norfolk and Suffolk had increased, and there had also been positive developments in Essex.

“There has been a reversal in the fortunes in schools in Basildon, where a teaching school has been training teachers across the entire (local) authority. Our aim is to get that model more consistently.”

But Duncan Spalding, head of Aylsham High School in north Norfolk, said solving recruitment issues was not a main element of the role of teaching schools: “That’s not the main part of their remit.”

His school does not have a recruitment problem, “but there are clearly huge challenges across the patch”. Finding and keeping teachers required a “many-faceted strategy”, according to Mr Spalding.

He added: “We have school leaders working with all sorts of providers to develop a strategy to encourage NQTs to come to the region, to stay, and to really improve standards.”

Your thoughts