Ofsted’s focus on curriculum risks being a tick-box exercise that does nothing to assess whether children are actually learning, warned a prominent education academic.

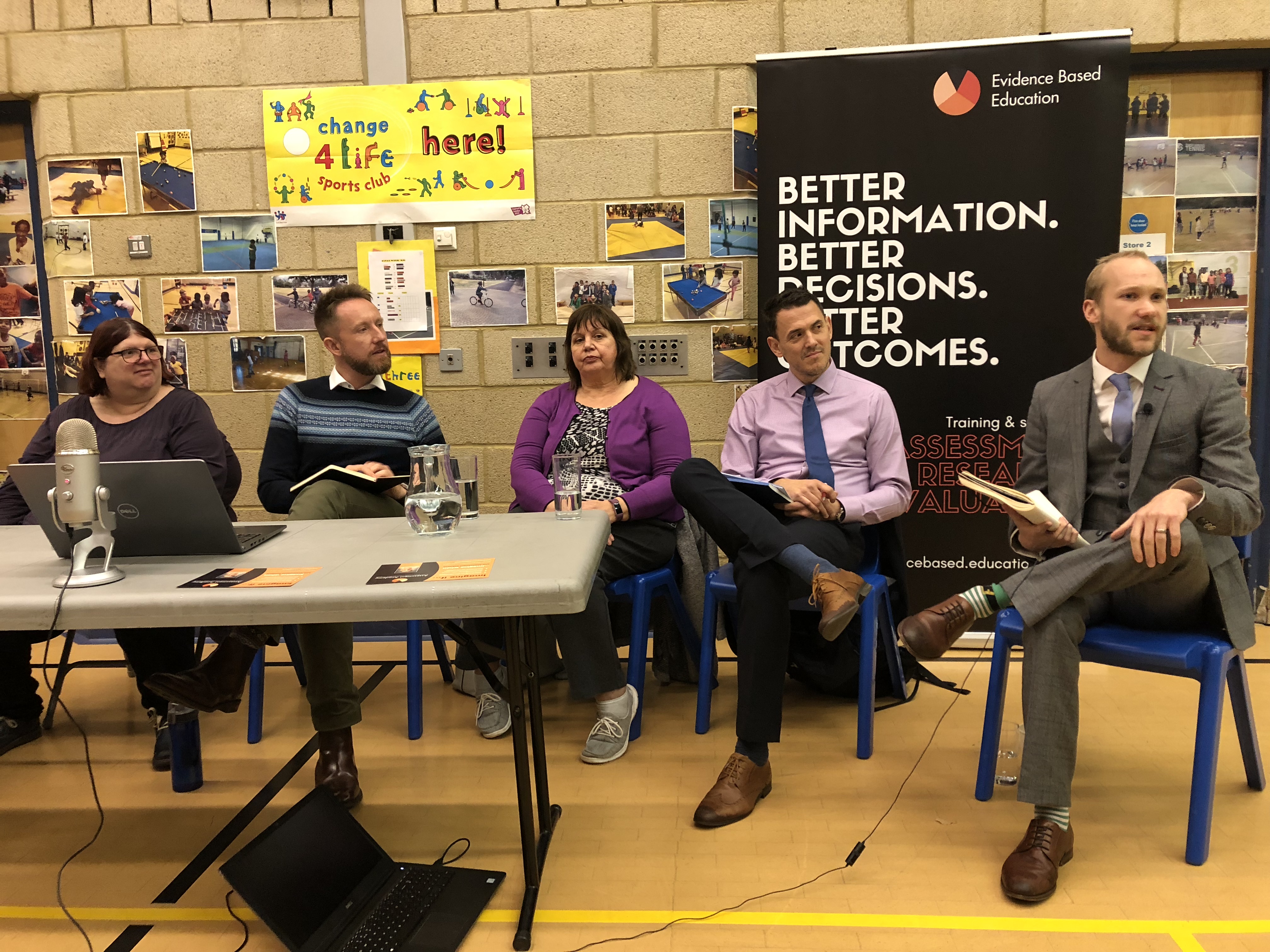

“Working out whether somebody has learned something or not is incredibly complex,” said Becky Allen, professor of education at University College London’s Institute of Education, at a panel event on assessment organised by research organisation Evidence Based Education.

By emphasising curriculum while ignoring that question, the inspectorate “risks us actually going back to the age of just writing down curriculums as a set of tick statements and we just tick them off as we’ve done them.

“That is absolutely not the way we decide how a child’s knowledge domain is being built up or mastered at all. If only it were that easy, that we just assess the curriculum. But it’s more complicated than that.”

Ofsted chief inspector Amanda Spielman has previously denied that Ofsted’s focus on curriculum is a “pub-quiz” approach and has indicated that the new framework will look at not only the curriculum intent, but also how it is implemented, as well as the results, outcomes and destinations of young people.

Schools should test students more frequently and aggregate the results to build a more accurate picture of learning, said Allen. “I’d just say we can test more frequently and form a more holistic view of how good somebody is at a subject and what they know.”

Technology could eventually get to a point where instead of exams in sports halls, summative assessment was done by combining these aggregated test results with other performance data, predicted Allen: “I think at some point the way we will form a perspective on how good someone is at a subject is through the process of collating class and homework information.”

Schools have struggled to work out how to track pupil progress internally since levels were scrapped in 2015, with too many replacing them with “summative assessment systems that are levels by another name”, warned panel member Jon Hutchinson, foundation curriculum lead at Reach Academy Feltham.

The danger with systems akin to the old levels, such as “flight paths”, added Dr Christine Harrison of King’s College London, was that they risk putting too much emphasis on SATs and GCSEs, to the detriment of formative assessment, which is designed to check learning in order to better target teaching.

The “proper place” of assessment is “as a servant of the curriculum, and of pedagogy, not as a driver,” added Dr Harrison.

In one of her more controversial interjections, Allen told the audience that the best reason for teachers to become experts in assessment is to defend themselves against line managers making “largely unwarranted” inferences about their practice.

“I would argue that becoming an expert in assessment yourself is your best weapon against your managers who are erroneously using assessment data … as a control device to assert whether or not you’re good at your job.”

Contributions from each of the panellists can be found in the What every teacher needs to know about assessment ebook.

Your thoughts