England’s academies are failing to capitalise on the “best ideas”, says the OECD’s head of education, calling for more opportunities for teachers to share knowledge and participate in research.

In an exclusive interview with Schools Week, Andreas Schleicher warned that teachers in England “have very little time for other things than teaching”, which harmed retention and the country’s standing in international league tables.

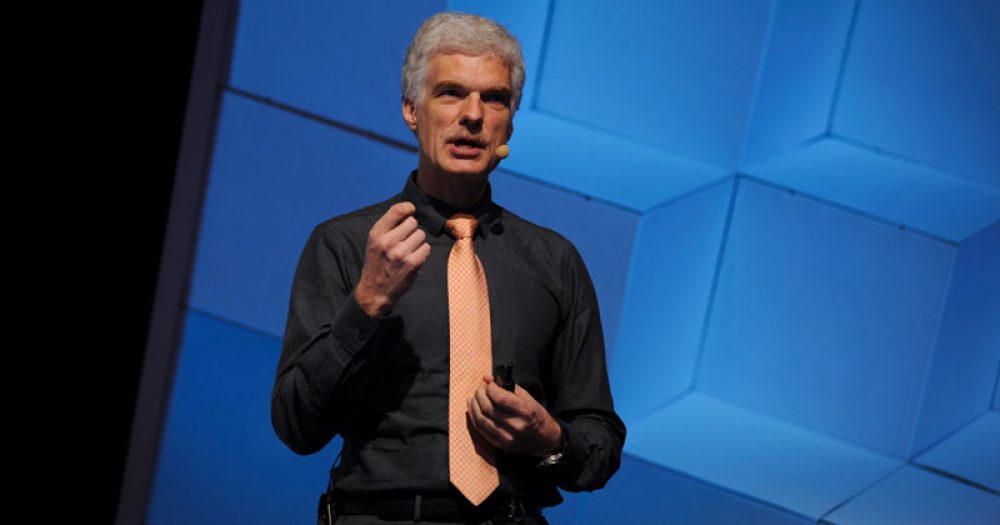

Speaking at the WISE Education Futures conference in Paris last week, Schleicher called on schools to involve teachers in education reforms to make the profession more “intellectually attractive”, rather than focus on financial incentives.

If teachers are developing good ideas in isolation, that’s not going to help the system advance

Ahead of his speech, Schleicher told Schools Week the academies programme was a “good move”, but England needed to “take care” that the autonomy of the system was not squandered.

“Compare yourself with the Netherlands, where every school is an academy. The difference is the Netherlands at the same time has strong systems. So these autonomous schools actually collaborate, they share ideas, they share people.

“It’s quite easy for a teacher to move from one school to the next, one pedagogical idea to the next. That I find missing in England. England has strengthened school autonomy, but I do think [it has] that kind of overall coherent system, that capacity of schools to collaborate across academy chains and so on.”

Last year Sir David Carter, the former national schools commissioner, called for more trust-to-trust collaboration, urging academy trusts to “over-recruit” teachers and leaders so they could help to turn around schools outside their organisations and become so-called “system leaders”.

Schleicher warned that too many ideas flowed into schools from above, and not “laterally” from teachers.

“I value very much the autonomy [for schools], I think that’s a very important ingredient for success, to liberate good ideas, but at the same time if teachers are developing good ideas in isolation, that’s not going to help the system advance.”

Schleicher is also critical of England’s focus on a knowledge-rich curriculum, and warned it was a “grave mistake to pit knowledge versus competence at two opposing ends of a spectrum”. Neither was of value without the other.

“We need to understand that the world is changing. The kind of things that are easy to teach, easy to test are now all too easy to digitise, to automate.

“The rise in social and emotional skills is very clear; collaborative skills, the rise in creative skills, imaginative skills. In a way, schools are very conservative social systems, and as parents we are sometimes actually part of the problem.

“We get very nervous when our children no longer learn things that we used to learn, or we get even more anxious when our children learn things that we have not learned.”

If England is to perform better in the PISA tests, an international study run by the OECD that ranks 70 countries based on a test of 15-year-olds, Schleicher said its pupils must demonstrate a deeper “conceptual understanding” of their subjects.

In 2015, the UK was 27th out of the 70 countries for maths, 21st for reading and 15th for science.

The results, Schleicher said, demonstrated that English pupils did well in tasks that “typically relate to relatively shallow tasks of knowledge reproduction”, but that was not what PISA was looking for.

“The type of tasks where British students do a lot less well are tasks where you need to elaborate, where you need to connect new material with what you know.

“Deep conceptual understanding, you can pinpoint that pretty clearly. But if Britain wants to do better on PISA it should probably teach fewer things at greater depth, focus more on conceptual understanding.”

He also warned of the prevalence of “memorisation strategies” in English classrooms, which he said were “no longer helping” pupils.

“If you look into a British classroom in a maths lesson, you typically deal with 15, 16, 17 problems in one lesson. If you go to a Japanese lesson, you deal with one problem.

“The idea is to really see what the origin of the problem is and develop different solution strategies, to have students demonstrate that they understand the fundamental concepts and actually use them, and then they can extrapolate from this.”

I’m not sure Schleicher fully understands England’s academies. He says they’ve increased autonomy. But the OECD which employs him said following the 2009 PISA tests that the UK already had more autonomy than most other systems. That was before mass academization. At the same time, we know that schools which join a MAT risk losing their autonomy especially when trustees impose a uniform curriculum or methodology. Rather than increasing autonomy, academization has reduced it.

Schools Week might want to ask Schleicher why anyone should trust PISA if participant systems are trying to game it by prepping those taking the tests.

If Schleicher wants to learn more about teacher involvement in the curriculum, he may find the current development of an English ‘Model Music Curriculum’ of interest. This has been proposed very recently and is to be overseen by a board of 14 that includes just one teacher. The organisation chosen to write this new curriculum is the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music (ABRSM). This is an organisation with no background in whole class music teaching in schools. Even more telling is the consultation period that is to last just two weeks!

This is quite normal in the English education system where teachers are evidently not trusted. Teachers are regarded with disdain and frequently referred to – by ‘educated’ and influential politicians – as the ‘blob’ to express this disdain.

Schleicher may also find my opinion of academies of interest as he does not appear to share it: the academies program is primarily driven by a desire to break up the state provision of schooling. Any positive outcomes, such as ‘increased autonomy’ (arguably non-existent, see Janet Downs’s comments above) are incidental. The main objective behind the academies program is to dismantle the state provision of this public service. After all, there is no evidence that the academies program has improved outcomes for children. This is also true of its cousin, the Charter School system, in the U.S. also driven by the same anti-state ideology.