The brightest students are missing out on offers from universities compared to their lower scoring peers, figures from university admissions body UCAS have revealed.

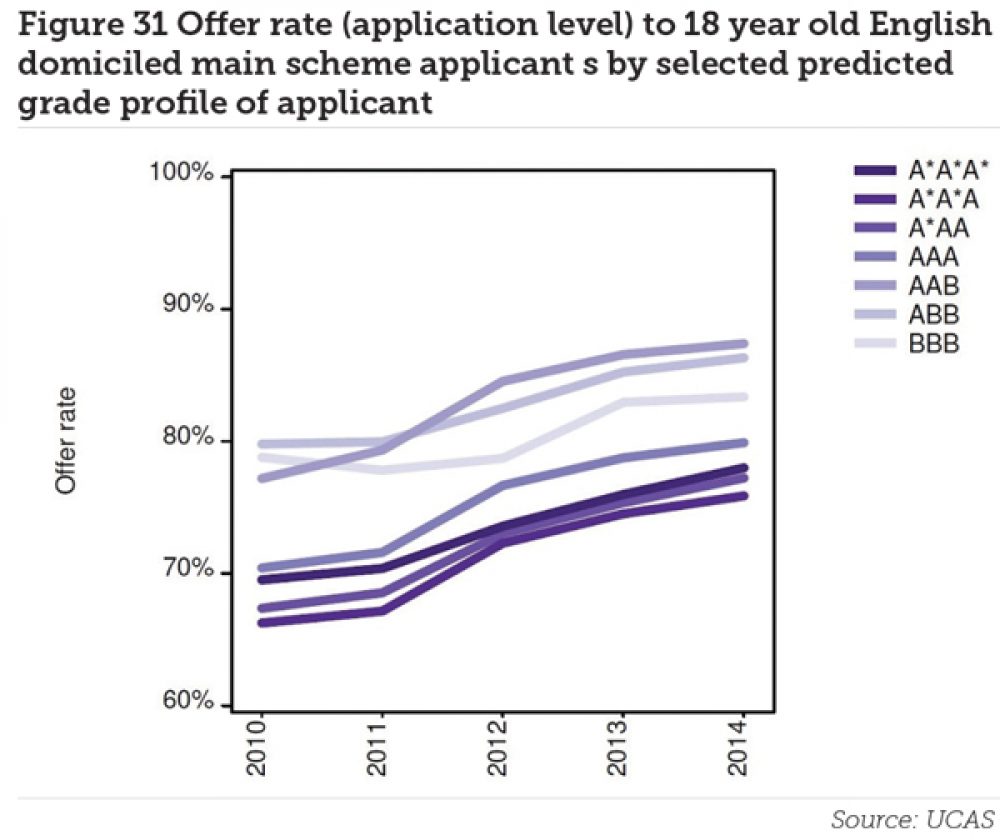

The latest End of Cycle report from UCAS shows students who applied to start university in September last year with at least one predicted A* grade were accepted at less than 75 per cent of their choices, while those predicted AAB received offers 87.4 per cent of the time.

The reason given for this discrepancy by UCAS in its 139-page report is that courses entered by those with high grades are “competitive”. But when asked to explain the reasons further, the service was unable to do so.

Only 8.2 per cent of A-level exam entries reap an A* grade, whereas 52 per cent of exam entries return a grade of B or above, suggesting there are many more students in receipt of AAB grades than three A*s.

Several universities and Universities UK were unable to comment further on the finding. However, head of admissions at Southampton University, Nick Hull, said the finding was due to more higher-grade students wanting to study subjects that needed high grades, such as medicine, than there were places available.

Mr Hull said: “While at a first glance it would seem perverse that applicants predicted the highest grades will be made fewer offers than those predicted a grade or two lower, one also has to take into account the range of institutions those applicants have applied to and the subjects they have applied to study.”

He said guidance from schools and colleges enabled pupils to understand the different entry requirements and to have realistic expectations, and in subjects like dentistry and medicine there were extra means to select between candidates, such as the UKCAT test.

Mr Hull added: “It is unlikely that large numbers of applicants not predicted the highest grades will apply to study these subjects, while at the same time there are far more high quality applicants wanting to study these subjects than there are places.”

Jude Heaton, head of higher education access and employability at TeachFirst, which runs the Futures programme aimed at helping pupils from low-income families into top universities, agreed with Mr Hull’s assessment.

He said students were often pushed into doing oversubscribed “career” degrees rather than applying for broad subjects where they had more chance of getting a place.

Mr Heaton said: “Pupils aren’t getting places which match their ability and aspirations. They need support from the wider world to get them there.

“There needs to be an awareness of the outcomes of doing certain courses. Many students apply to do medicine, or law, or business, because it has a clear career, whereas it can be better to apply for something like classics at Oxford and you are still going to get a good job.”

The UCAS report said: “The rank order of the level of offer-making to applicants holding each of these profiles is complex, reflecting both provider decisions and the applicant choice of course.

“For example, the offer rate to applications from applicants predicted AAB is higher than for those predicted BBB. But when applicants are predicted one or more A* grades, the offer rate goes down again, reflecting the competiveness of the most selective courses.”

Your thoughts