The number of pupils receiving whole-class ensemble teaching through music education hubs has risen by a fifth since 2013, however a new study has also found a “worrying drop” in the take-up of area-based ensembles by older pupils.

The drop in numbers of youngsters playing in “area-based ensembles” – particularly those aged 14 to 18 – was revealed in a report on music education hubs, released today by Birmingham City University.

The hubs, an idea first mooted in 2011, are groups of organisations – such as local authorities, schools, and community organisations – working to boost music education provision for young people. In 2016-17 there were 120 hubs across all local authorities in England, which are backed by £300 million government funding and run by Arts Council of England.

Their aims include ensuring that every child aged five to 18 has the chance to learn a musical instrument through playing in a whole-class ensemble, making sure clear progression routes in music are available and affordable, and providing opportunities to perform from an early stage. They work with schools, but also support and deliver other groups and choirs for young people in their local area.

The findings come as the government faces pressure over claims its focus on EBacc is driving creative subjects such as music out of the curriculum – something recently denied by schools minister Nick Gibb.

The report found 89 per cent of schools benefited from support of the hubs, up from 84 per cent in 2013-14. In total, 711,241 pupils received whole-class ensemble teaching through the hubs, up from 596,820 in 2013-14 (up by nearly 20 per cent).

The hubs supported or delivered a total of 16,809 ensembles and choirs in 2016-17, up from 14,866 the previous year. But overall, they have reached only 9.2 per cent of the total population in state-funded primary and secondary schools so far, the report found.

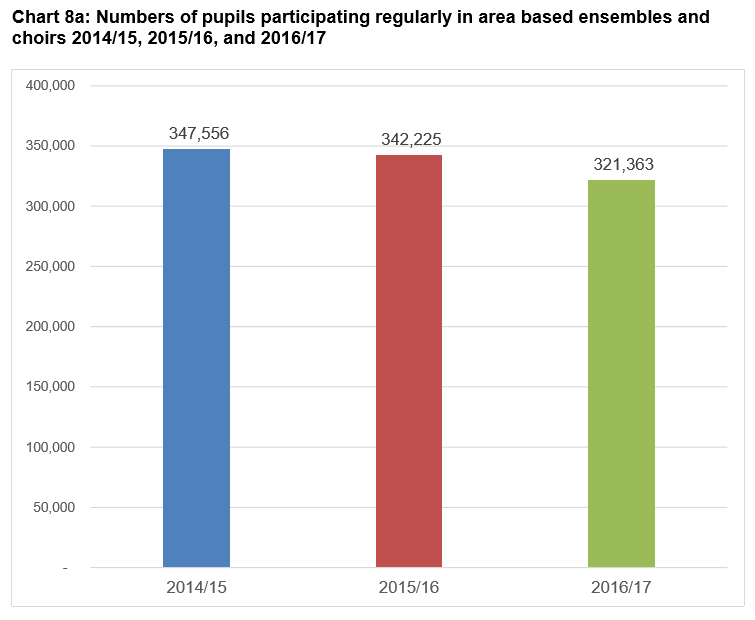

In particular, the numbers of young people playing in area-based ensembles fell by over six per cent between 2015-16 and 2016-17 (see chart 8a).

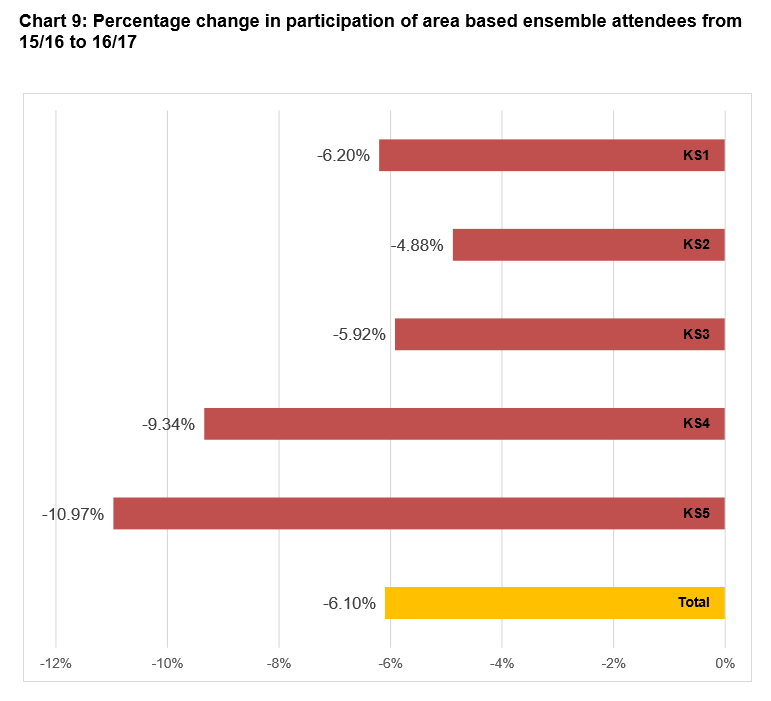

Broken down by age group, the proportion of key stage 5 pupils taking part fell by almost 11 per cent between 2015-16 and 2016-17, while the drop was over nine per cent for key stage 4 pupils (see chart 9).

While the fall does not necessarily mean that the total number of pupils participating in ensembles, including those within schools, has fallen overall, the report described it as a “worrying” development, especially as key stages 4 and 5 are “where it would reasonable to assume the largest numbers of more advanced young musicians are to be found”.

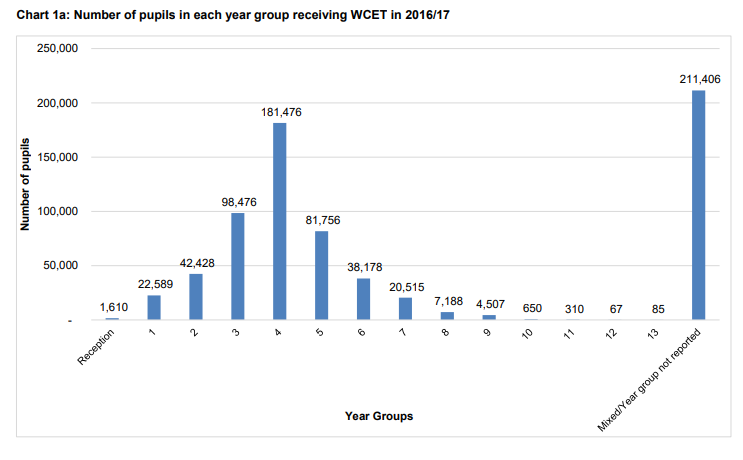

Looking at whole class ensemble teaching, the research found this approach was particularly successful with primary school pupils, reaching, for example, 181,476 year 4 pupils in 2016-17 (See chart 1a).

But numbers were much weaker in secondary schools again, with only 650 year 10 and 310 year 11 pupils receiving whole class ensemble teaching in the same year.

However, whole class ensemble teaching had a positive impact on the young people who received it, with 182,602 pupils continuing to learn an instrument after playing with their whole class in 2016-17, up from 166,529 in 2013-14.

Gender, SEN and pupils premium

The study found that girls were over-represented among pupils participating in music activities at all ages.

This was especially noticeable at key stage 3, where girls made up 60.2 per cent of ensemble attendance, but only 48.9 per cent of the school population.

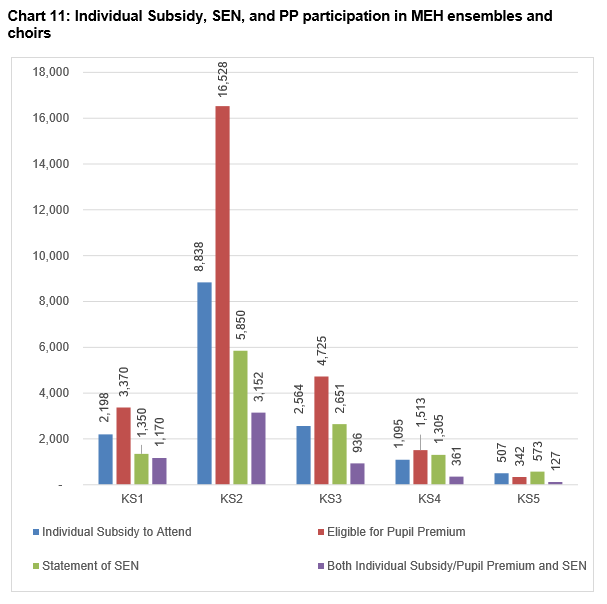

In contrast, participation among pupils with special educational needs (SEN) was low (see chart 11).

Analysis showed that 5.4 per cent of the pupils participating in area-based ensembles and choirs were identified as having SEN, a lower percentage than the 14.4 per cent with SEN nationally.

Around 8.2 per cent of young people eligible for the pupil premium participated, despite this group making up 28.9 per cent of the national pupil population.

Between 2015-16 and 2016-17, the number of pupils with a statement of SEN receiving whole class ensemble teaching fell by 2.0 per cent, and those pupils eligible for the pupil premium dropped by 4.5 per cent.

Gibb said that learning a musical instrument “opens all kinds of opportunities for children to express themselves, whether it’s being part of a band or orchestra or just playing for pleasure at home”.

“Our continued support for the arts, which is the second highest funded element of the curriculum behind sport, will see almost £500m invested between 2016 and 2020 – with £300 million supporting the work of music hubs to make sure more and more pupils have the opportunity to learn an instrument.”

Birmingham City University carried out the analysis on behalf of Arts Council England, looking at data collected in an annual survey.

Music hubs do valuable work but are no substitute for high-quality music education in all schools. But this costs money. Setting up hubs is cheaper but don’t reach all children especially those in rural areas or outside cities (compare the number of hubs within London with rural counties).

Music hubs should be viewed as supplementary to music provision in schools. But all too often they’re viewed as a substitute (and, of course, allow ministers to crow about their commitment to the arts while school funding is inadequate).