Love them or loathe them, mobile phones are high in any popularity poll. Children often seem to have them glued to their hands. But do they have a place in the classroom?

In June last year, Amanda Spielman, the chief inspector of Ofsted, said that she supported a ban in schools because they interrupted learning and made teachers’ jobs more difficult. “There’s no doubt that technology has made the challenge of low-level disruption even worse.”

Do mobile phones have a place in the classroom?

But other education leaders say that allowing pupils to use their phone as a resource to record and look up information is a good thing. Forget the pros and cons, however. What are schools actually practising?

Schools have the freedom to regulate the use of phones amongst pupils and, according to the Department for Education, 95 per cent of them exercise this right in some way. It is the norm for a school to have a mobile phone policy.

Where they differ is in what that policy says. Some teachers collect phones at the beginning of the day, others only allow them to be used during break times. According to our recent Teacher Tapp survey, most primary schools either ban phones or collect them, whereas secondary schools are more varied: just 4 per cent impose an outright ban. This makes sense, given that older pupils will typically travel to school on their own and may attend after-school activities.

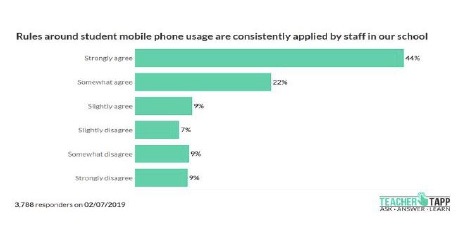

What a policy says and how people behave in a school may differ, however. We found from our panel of nearly 4,000 teachers that 25 per cent of them disagreed that rules around student mobile phone usage were consistently applied in their school. On the bright side, this means that three-quarters of teachers agree to some extent, which suggests that most policies are effective.

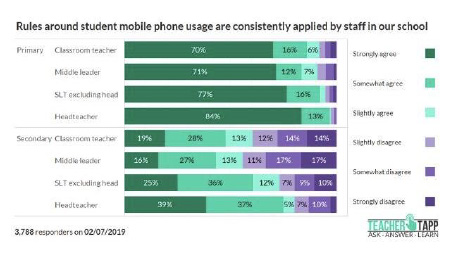

Headteachers were the most likely to strongly agree that rules are consistently applied – 84 per cent in primary and 39 per cent in secondary, compared with 70 per cent of primary classroom teachers and 19 per cent in secondaries. Could this suggest that heads are overly optimistic and out-of-touch with some of the goings-on in their school?

A potentially counter-intuitive finding for those who think all millennials are addicted to their phones, is that newer, and therefore usually younger, teachers are less permissive towards phone use. Maybe this generation’s constant immersion makes them hyper-aware of just how distracting phones can be. Considering that newer teachers are the ones that tend to struggle more with behaviour problems, they are also likely to feel it is important to reduce low-level disruption. No Snapchatting in class then – sorry kids!

So what is the best policy for schools? For some, a complete boycott may seem a great idea, but implementing a ban is easier said than done. Can you really ensure none is smuggled past the gate? And is it worth the effort?

In February of this year Damian Hinds, the education secretary, announced that the government would not support a mobile phone ban in schools. But, as stated, schools are free to set their own rules. Enjoy the freedoms while they last!

Your thoughts