In a five-part series, Schools Week is exploring the way vulnerable groups of learners have been treated under the Coalition – and asks what can be expected for them in coming years. In the first of the series, Sophie Scott reveals the invisibility of pupils with mental health needs

In a week when the education secretary touted young people’s “resilience and grit” as top of the agenda and began handing out a portion of the £9.8 million set aside for schools to build “character”, we are asking: where is the push for looking after pupils’ mental health?

Rarely mentioned in the past four years, Schools Week has spoken exclusively to politicians in the health field who reveal there is no accurate, up-to-date figures on the prevalence of mental health disorders of those aged under 18 – leaving policymakers floundering as to what provision to fund for school-aged children.

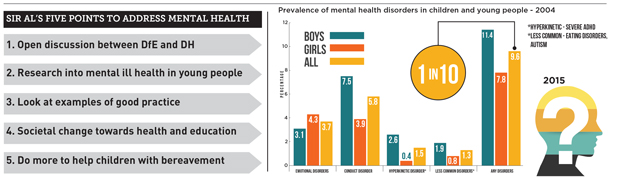

Both Liberal Democrat MP Norman Lamb, the minister of state for care and support, and former children’s commissioner and president-elect of the British Medical Association, Sir Al Aynsley-Green, feel that government policy is ignorant of the issue, and point to concern over the lack of data.

The Department of Health (DH) does publish figures on the number of people accessing mental health services – but only for those aged 18 and over.

The government has not published any data on the prevalence of mental health in children and young people since 2004. Previously it was undertaken on a five-yearly basis, collated by the Office of National Statistics (ONS).

The health select committee raised serious concerns about the missing data in its November report on “Children’s and adolescents’ mental health and CAMHS [Children and Adolescent Mental Health Services]”.

The chief medical officer’s annual report for 2012, published in autumn 2013, also highlighted the need for a repeat of the ONS survey and suggested there had been a rise in levels of psychological distress and self-harm in young people.

But there may now be light at the end of this ten-year-old tunnel.

In an exclusive interview, Mr Lamb said: “I’ve now got the money to do another prevalence survey, which is being designed at the moment. It will take place over the next financial year.

“All we can do at the moment is rely on anecdotal evidence. I think there’s quite a consensus that [mental health disorders] appear to have increased.”

The DH is still commissioning the survey, but Mr Lamb expects it to be published in 2017 by the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC).

The exact cost of data collection is not yet known, but Mr Lamb says it will be more comprehensive than, yet comparable to, the 2004 figures and will include new issues such as cyberbullying.

In 2004, one in ten children had a mental health problem, with most having emotional and/or conduct disorders. The figures were broadly similar in 1999.

Sir Al says that using these figures, about 100 children in a typical 1,000-pupil secondary school will be suffering from significant mental illness, including depression, obsessive compulsive or eating disorders, or experiencing bereavement, yet only a quarter could access the services needed.

But without data it is difficult to know which services are needed, and where they ought to be located.

“I call for new research to understand exactly what the current situation is, without which we cannot make serious, constructive comments.” Sir Al said

“There needs to be more open dialogue between the DH and the Department for Education (DfE).”

In particular, Sir Al argues that discontinuation of Every Child Matters, an initiative that encouraged schools to support broader health and safe-guarding aims for children, has made matters worse as benchmarks are no longer tracked.

There was no consensus when Schools Week asked the ONS, HSCIC and DH why there has been no collation of data since 2004.

The role of schools in mental health

Guidance for staff on mental health and behaviour in schools, published last June by the DfE, suggests that teachers and staff give questionnaires to pupils that raise concerns and then refer them to the correct service.

A review, due in October, has not yet been completed. The department says that it is currently carrying out a “small-scale review” that will be “updated in due course” but declined to say why the review had not been completed as planned.

Speaking about the guidance, Mr Lamb says: “[this] clearly isn’t enough. We need quite a fundamental improvement in the way we intervene and identify these problems. Part of it is the training of teachers. Minded [ an online mental health portal for teachers] is critical, but so is the basic teacher training.

“I suspect there are many teachers who feel, because they don’t have the training, quite nervous about mental health.”

Some schools are, however, finding new ways to support children with emotional difficulties.

Sir Al points to Penair School in Cornwall, and the Waves programme in Weymouth, as good examples.

However, he has concerns about children who suffer bereavement. “A child loses a parent through death every 20 minutes in our country. It is just one aspect of emotional burdens, but it is surprising how badly and ineffective those children are looked after. Many schools have so much to do they may not have the time or resources to address bereavement.”

Mr Lamb says that many school do not know who to contact within CAHMS. “[We have] got to stop calling it CAHMS. We talk in a language – tiers one, two, three and four; no ordinary person has the faintest idea what we’re talking about – we’ve got to use ordinary language so people understand.

“There needs to be a much closer link between schools and mental health services, not this great chasm where you make a referral and it ends up taking weeks to get anywhere.

“And worse than anything, in a way, is the stigma that’s attached to that referral… if you think of a vulnerable 15-year-old, the additional pressure that imposes on someone. I’ve heard a young person say ‘I’m the only one who’s going mad’. Just imagine how awful that is for a youngster to feel like that.”

He believes talk about mental health should be normalised: “If we could just seek to address those much more quickly in a non-stigmatised way, then I think we can make a big difference to the way in which services respond to people.”

What should happen next to support mental health provision in schools?

The health select committee makes three recommendations in its latest report. The cross-party group of MPs wants the DfE to include a mandatory module on mental health in initial teacher training and include mental health modules in continued professional development for teachers and support staff.

Mr Lamb supports this, but says that he doesn’t expect teachers or staff to be “experts” but to have better understanding to help make the right judgments about whether intervention is necessary. He also points out that the Lib Dems want mental health and mental wellbeing to be part of the national curriculum.

The committee also wants the DfE to audit mental health provision within schools, specifically looking at how well its June guidance has been implemented. It recommends Ofsted also make

routine assessments of mental health provision in schools.

Finally, the committee suggests the DfE consults with young people to ensure mental health within the curriculum meets their needs.

Sir Al believes the government needs to look at what is already being done successfully.

“Look to those places to build upon. The mental health of our children and young people is everybody’s business, and we have to get the importance of these issues into society, generally.”

And how do we know any future changes are successful?

Mr Lamb says: “As much as possible we need to try to make sure that we evaluate, in a scientific way, the interventions; that we try to make sure that we understand how best to use public money to most effect.”

Sir Al is calling for teachers and young people to tell him about the barriers they

face between education and health, what causes those barriers, and what they think can be done to overcome those barriers.

If you have any ideas, email news@schoolsweek.co.uk, and Schools Week will pass these on to Sir Al.

Good practice

There are many good cases of school support for children with mental health problems.

Norman Lamb points to the Mancroft Advice Project (MAP) in Norwich, while Sir Al praises Penair School in Cornwall’s “Bywva Centre”, headed by the Duchy Health Charity. It aims to bring together professionals from health and education to “explore ways of enhancing the lives of young people, encouraging them to take increasing responsibility for their own wellbeing”.

Speaking about MAP, Mr Lamb said: “What I absolutely see is the need for much better in-school support.

“This is one of a network of young people’s advice and information networks, so it’s third sector and it’s a very non-stigmatised, easy-access support service for young people with the whole principle of early intervention.

“Part of the service it offers – and it has reached agreement with a number of schools to do this – is to go into schools for lunchtime sessions. Any young person can come along and just talk confidentially.

“It’s not a referral to a mental health service, it’s the chance to address anxieties/problems/angst.

“Quite often students don’t actually want to talk to a teacher, they don’t want to talk to a formal school-appointed person – they quite like the sort of slight anonymity of a conversation, and the confidentiality of the conversation, with someone coming in.

“Critically, it’s going to be coming in rather than a referral out, so the principle about catching things early in school is critical, although I’m open-minded about the right approach to achieving the best results.”

The DfE’s ‘fresh focus’

Advice on “good counselling” in schools is to be published this spring by the DfE.

The department is also offering grants to organisations that can “improve the identification of children’s mental health issues, their prevention and the better commissioning of support and collaboration between agencies and services”.

It has identified mental health as one of seven priority themes in its voluntary, community and social enterprise grant scheme.

A DfE spokesperson said: “We are placing a fresh focus on improving young people’s mental health and providing opportunities for young people to develop the character and resilience they need to succeed in modern Britain.

“Good schools recognise the importance of children and young people’s wellbeing on their attainment, and have a duty to promote mental and physical development.”

This month, the Children’s Social Care Innovation Programme awarded £8.4 million to projects that support young people with mental health problems who are in care, or at risk of coming into care.

The PSHE Association has also been commissioned to produce guidance on teaching about mental health issues. “In addition we are working closely with the Department of Health’s mental health and wellbeing taskforce, which is looking at how to improve the provision of children’s mental health services and will report back next month,” said the spokesperson.

“We want to ensure any update to the mental health and behaviour advice to schools aligns with this work.”

Guidance for teachers lists the risk factors

The guidance that the DfE published last June gives examples of questionnaires teachers can ask pupils to complete, mental health “factsheets” to help identify potential issues and “teacher training toolkits”.

The DfE says schools should use this 47-page document to tackle problems before they become more serious and to refer pupils to the right mental health experts. It also tells them to look at available local provision.

The document lists a number of “risk factors” for young people, including communication difficulties, genetic influences and academic failure, and suggests schools use attainment data and have an “effective pastoral system” to identify at risk children. It also gives examples of how to create stable environments for pupils, including peer mentoring systems, clear bullying and behaviour policies and discussing mental health issues as part of the wider curriculum.

But the guidance has been claimed to fall short of providing a “solution”. In evidence to the health committee, Anthony Smythe of BeatBullying said: “It touched on CPD, but it was disappointing that there was not more in there. We need a lot more investment. The government is very good at saying what needs to be done, but more needs to be done on the how — the sharing of good practice and the teacher training part of it.”

The charity and its sister organisation MindFull, which offered young people support for mental health issues, and

ran helplines, online forums and counselling sessions, went into liquidation late last year.

With the term “stigma” you are bullying.

Such an important issue to address. I am having to deal with an increasing number of mental health issues on a day-to-day basis, and finding timely and effective intervention and support is becoming increasingly difficult.

We offered our first MHFAEngland accredited training for school staff and governors in January and the reponse to it from the 11 Heads, Governors, SLT, SENCos and TAs who attended has been overwhelming. One delegate contacted us afterwards to ask for further support with a self-harm situation and also to let us know that the non-judgemental listening skills learned on the course had enabled her to support the student more effectively. Huge need – mental health first aid training benefits the whole school community, not only young people but also staff, parents and all who come into contact with the trained person/people #raisingawarenessreducingstigma

So pleased to see Schools Week tackling this – we cannot speak loudly enough about young people’s mental health. Young people that are suffering from problems associated with mental health illness need help now. Interim practical solutions need to be funded and put in place today – these young people cannot wait until the data is available in 2017. I would also challenge whether the the DH and DfE are yet truly joined up on this given what appears to be very low representation of educational professionals on the NHS CAMHS task force. The committee referred to should also be consulting with parents – some of these mental health problems could be identified earlier in primary school age children which would lead to much earlier intervention and support. I do however worry about the ‘selective’ questionnaires approach, surely a process where all young people could complete a questionnaire that was then reviewed by an appropriate professional to spot where there may be problems would be a better approach that way you don’t single young people out or expect unqualified people o interpret the information. Please keep up the profile Schools Week.

We provide a service in 95% off all primary schools and 75% in secondary schools in one local authority. Crucial for early intervention strategy

where can i find the other four parts of the series?