Prime minister Boris Johnson is set to reveal his “comprehensive” plan for how schools will reopen. What do we know? What are schools doing? And how has it worked in other countries? Schools Week investigates.

This Sunday Boris Johnson is expected to announce details of his plan to allow children to return to schools, while headteachers wait for guidance on how they will keep their staff and pupils safe.

It is understood the announcement will form part of a wider address on the government’s strategy for ending the lockdown. It’s expected detailed guidance will then be revealed in the commons on Monday.

However, Gavin Williamson, the education secretary, reiterated this week that any return would be phased, based on scientific and medical advice, and with “maximum notice” for schools.

The Guardian reported last week that government advisers were examining the impact of allowing year 6 pupils to return on June 1, with other primary children and year 10 and 12 pupils back soon after.

June 1 would give schools the three weeks’ notice proposed by the government in its dealings with headteacher unions, although some heads said this was not enough time to prepare.

Do schools think it’s feasible to reopen?

Unions have been talking to the government throughout the week.

The National Education Union (NEU) has set out its own tests, warning that if schools opened too early there was a “very real risk” of another spike.

Before pupils go back to classrooms, the teachers’ union wants a national plan for social distancing and PPE, access to regular testing for children and staff, protocols for whole-school testing if there is a case, and protection for vulnerable staff and parents. It also says pupils should not go back unless the number of Covid-19 cases falls.

School leaders, as they have done throughout the pandemic, have come up with their own ideas.

The Harris Federation has installed sink troughs in the playground for children to wash their hands. It is also looking at splitting school days in half.

Huntington School in York, which has been planning for two weeks for a possible reopening, has bought 16 mobile washing stations for anyone coming in and out of school. Each cost £640.

But there’s also concern about the safety of teachers.

Stuart Lock, the chief executive at Advantage Schools, said there would need to be “flexibility” for him to be able to say “stay at home if you are vulnerable or have families that are vulnerable”.

A snap poll by the NEU this week of more than 2,000 mainstream school staff found that nearly a quarter were having to stay at home to shield themselves or a household member.

Lock added: “I recognise that some of our disadvantaged pupils could be missing out on education, but we have to balance the risk – my biggest fear is making a decision that will cause someone whose wellbeing I have responsibility for to die.”

He also said there was a “reality” that pupils and staff would have known someone who had died, so all staff had been trained online on how to deal with bereavement.

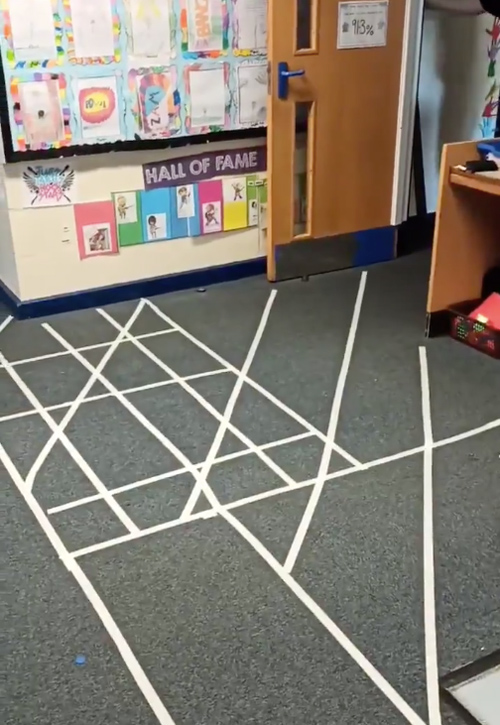

The practical consideration of having enough space to keep people apart is also a worry.

Dr Sharon Wright, a senior associate at the-learning-crowd, a design company that has been involved in school building projects since 2004, estimated a standard classroom could have no more than ten pupils.

There may also be bigger problems for newer schools built under the Priority School Building Programme introduced by Michael Gove, the former education secretary. They were cheaper than those in the Building Schools for the Future programme it replaced, but they were also smaller.

Department for Education guidelines in 2014 show the standard secondary classroom for 30 children was 55 sq m – one square metre smaller than in 2004.

But Wright said the main space savings were in communal areas, such as corridors and dining spaces.

“Every school that I’ve seen discussing this has been saying we are going to have to introduce a one-way circulation system within the building.”

What’s happened in other countries?

Professor Yvonne Doyle, the medical director at Public Health England, said on Wednesday the government was watching other approaches, particularly in how countries were gaining the “critical” confidence of parents and teachers.

In mid-April Denmark was the first European country to reopen its schools. Some parents were initially reluctant to send their children back, but attendance numbers have reportedly risen.

Primary children returned first and eat, play and learn in separate groups of about a dozen pupils.

Dorte Lange, the vice-president of the Danish Union of Teachers, told the BBC that reopenings had been “quite successful”, adding there was a collective approach between teachers’ unions, local authorities and government.

She said the medical advice had focused on keeping pupils apart, with a strong emphasis on hygiene. This meant that a lack of personal protective equipment (PPE) – something unions have concern about in England – had not been an issue.

But last week Danish authorities, which have also allowed small businesses to reopen, reported an increase in the reproduction (R) rate of Covid-19, from 0.6 to 0.9 per cent.

The R rate represents how many other people are infected on average by someone with the virus. Governments want to keep this below 1, as it shows infection is decreasing.

However, Denmark’s State Serum Institute, which is overseeing the management of the pandemic in the country, said there were “no signs” that the epidemic was “accelerating”.

In France, president Emmanuel Macron went against advice from his scientific committee by pledging to reopen nursery and primary schools progressively from Monday, but all contact sports will be banned and objects touched by more than one pupil must be disinfected.

There will be a maximum of 15 pupils in staggered classes and breaks will be in shifts.

Younger students in Norway also returned in April with about 40 per cent of schools in Japan reported to have reopened.

In Wuhan, the Chinese city where the virus was first reported, children have been pictured learning behind transparent screens on their individual desks.

Some classes in Germany have also reopened, but lessons such as sport and music are not on offer.

Italy and Spain have said schools will not reopen until September. That also seems to be the message from Scotland.

Is it safe?

Williamson has commissioned a sub-group of the government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) to “look at the particular issue of opening schools” in the UK.

The evidence on children’s role in carrying Covid-19 and the impact it has on them appears inconclusive.

A review of evidence by the Chartered College of Teaching (CCT) said although the virus appeared to “generally affect children’s health less than adults and they may be less likely to contract it, less is known about children’s role in community spread”.

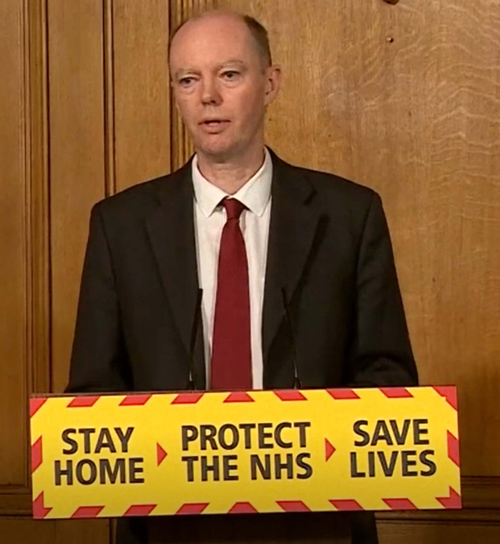

Chris Whitty, the chief medical officer, has said that while a “great majority of children” either do not contract the virus, or have mild symptoms, there was still not enough data on how they contributed to its spread.

There was “no doubt” that their attendance at school had an effect on R value.

The CCT paper said the “potential risks to students and teachers need to be taken into account when planning school reopenings, including age-related differences in children’s ability to understand and comply with social distancing measures”.

Special schools will face their own challenges

Graham Quinn, the chair of Special Schools’ Voice, said a significant proportion of young people who attended special schools would be unlikely to understand or follow social distancing.

“We still believe that many parents and carers will think their children will be safer at home,” Quinn, the executive principal of the New Bridge Group in Oldham, added.

Government figures show just 6 per cent of pupils were attending special schools as of last Thursday.

The Department for Education has admitted it would be impossible to provide the care that some pupils needed without hands-on contact. Guidance recommends an increased level of self-protection, such as minimising close contact and more frequent handwashing.

Ministers maintain educational staff do not require PPE, but some are now sourcing their own. Severndale Specialist Academy in Shrewbsury, one of the largest special schools in the country, has sourced its own PPE.

Special school heads also questioned how social distancing was possible on specialist transport needed to get some pupils to school.

Your thoughts