There is limited evidence on teacher autonomy, so the National Foundation for Educational Research has delved into data to find out what’s going on.

The report, said to be the first large-scale quantitative study of teacher autonomy in England, found teachers’ perceived autonomy over their jobs is strongly associated with greater job satisfaction and their intention to remain in the professions.

Schools Week has the key findings.

1. Teachers have among lowest autonomy …

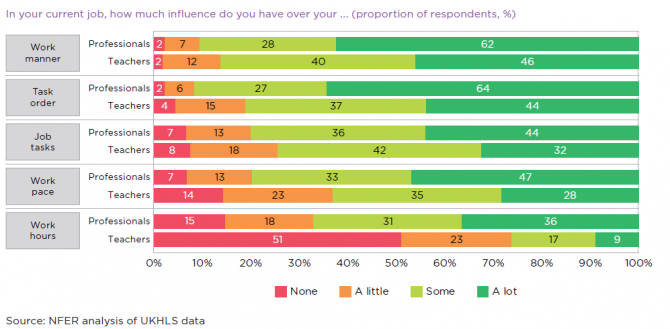

The report found half of teachers report having no autonomy over work hours, compared to only 15 per cent of similar professionals.

While the report said this is to be expected given the set term times and school hours, teachers had a lower level of autonomy over every aspect of work, including: job tasks, task order, work manner, and pace of work.

Only state-sector health professionals, which includes doctors and nurses, have lower autonomy.

But there is considerable variation between individuals within teaching, suggesting “there is scope for the profession as a whole to increase autonomy”.

2. … and fewer have ‘a lot’ of influence

The size of the autonomy gap between teachers and other professionals is a long-standing one, suggesting teacher autonomy hasn’t been affected much by policy changes since 2010.

However, the most notable change is a five percentage point fall in the number of teachers reporting they have “a lot” of influence over how they do their work, between 2010-11 to 2016-17.

It’s not statistically significant, but NFER suggests this “could represent an emerging downward trend that will continue in the future”.

3. Autonomy DOESN’T increase with age

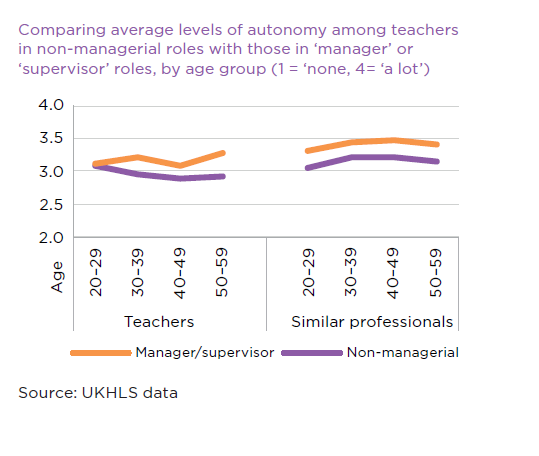

The findings go against the theory that autonomy grows as people become more competent, respected and trusted throughout their career. In fact, there’s actually a slightly decreasing relationship in age and autonomy for teachers.

This is in contrast to other professions (where autonomy increases between their 20s and 30s). Teachers in a manager or supervisor role have higher levels of autonomy.

4. Teachers have less influence in academy trusts

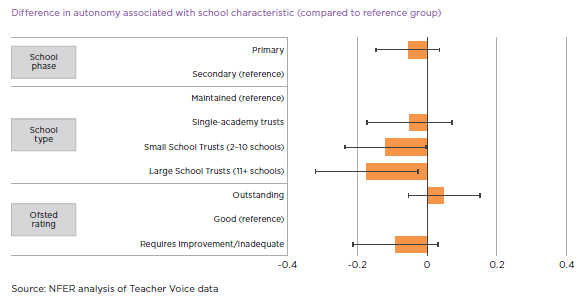

Autonomy was “significantly lower” for teachers in small and large school trusts (see image below).

NFER said this was linked to trusts “standardising or aligning practices across schools as they develop”, although this differs considerably by trust.

Teachers in ‘inadequate’ or ‘requires improvement’ schools also have less autonomy than those in ‘good’ schools, although the difference isn’t statistically significant.

5. Teachers with more freedom are happier in their jobs

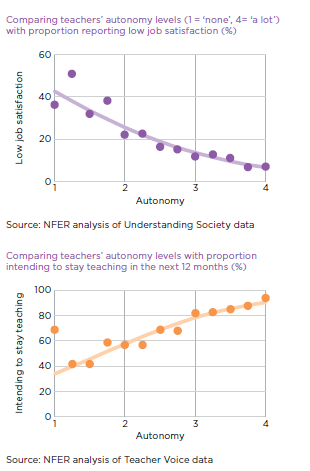

NFER found a positive relationship between autonomy and job satisfaction for teachers.

Around four in ten of teachers with the lowest autonomy reported low job satisfaction, compared to less than one in ten among those with the highest autonomy.

Teacher autonomy is associated with lower job‑related stress, too.

It’s also linked to retention: around half of those with the lowest autonomy are intending to stay in teaching in the short-term, compared to more than 85 per cent of those with the highest autonomy.

Specifically, teachers’ autonomy over their professional development goals is most associated with higher job satisfaction.

A one point increase in influence over teachers’ professional development goals is associated with a nine percentage point increase in their intention to stay in teaching, the report found.

6. What can schools do about it?

NFER suggests school leaders consider “incorporating a teacher autonomy lens to regular reviews of teaching and learning policies”.

Reviewing the school’s approach to professional development should be a “priority”, with the aim of getting teachers more involved in their goal-setting. The report also adds teachers should be more engaged in the way schools make decisions more widely.

Meanwhile, the Department for Education has been urged to produce guidance on teachers’ professional development standards to emphasise involving teachers more and embed those principles in the early career framework.

Your thoughts