The Conservative manifesto pledged to maintain per pupil funding across the lifetime of the next government. Given that other parts of the public sector are facing deep austerity measures, schools have been urged to think of themselves as fortunate for avoiding cuts. But upcoming changes to national insurance and pensions mean schools are facing rocketing pay bills without any extra money to cover it. Senior reporter John Dickens spoke with three school leaders from across the country to discuss the fine art of budget balancing. He reveals the cuts they have already had to make and the ones that are yet to come.

Headteachers will face crippling debt in their schools unless they take urgent action to slash spending, say three headteachers who allowed Schools Week access to their annual budgets to show just how devastating the cuts are.

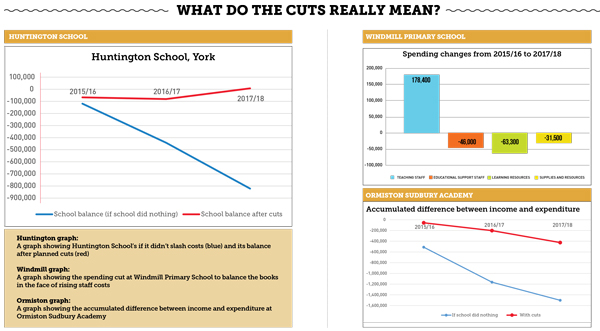

John Tomsett, head at Huntington School in York, has already trimmed £362,000 from his annual spend.

But, with increased pension and national insurance contributions due in the next 12 months, his school will be more than £800,000 in the red by 2018 if he doesn’t slash more.

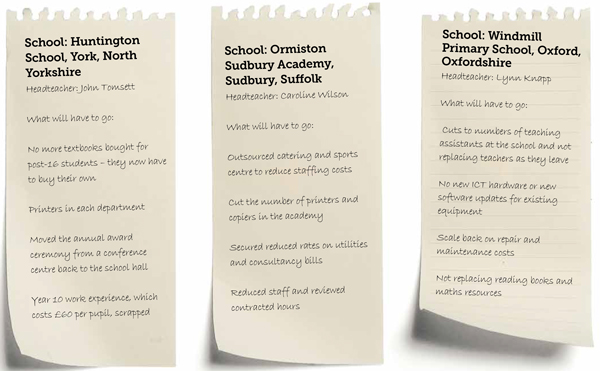

Instead he has taken the tough decision to cut work experience for year 10 pupils and move the annual awards ceremony from a conference centre back to the school hall.

But he warns: “I can make lots of little cuts, but nothing impacts like cutting into the costs of your staffing. That’s what it’s going to have to be next.”

Pension contributions are due to rise from 14.1 to 16.5 per cent in September. Schools will then face a hike in national insurance payments the following April, with the standard contribution rising from 10.4 to 13.8 per cent.

Staff wage increases and inflation also have to be taken into account – at a time of stagnant per-pupil funding.

Lynn Knapp, head of Windmill Primary, the biggest primary school in Oxford, estimates that the extra pension and national insurance costs for her 100-plus staff will amount to more than £80,000 a year.

“We’ve had to make stringent cuts to balance our budget up to 2018,” she says. “But it always comes back to staffing costs in the end, that’s our greatest cost.”

To meet the shortfall, her school has slashed spending on learning resources by almost half – from £139,600 this year to just £76,300 in 2017-18.

Education support staff have also taken a hit, with spend falling from £419,900 to £373,900.

In February, the Leeds School Forum estimated that schools would need to find annual savings of more than £1 billion to balance their budgets.

Unions have warned it could result in tens of thousands of job losses, and this week the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL) told George Osborne the funding pressures were putting the government’s education programme in jeopardy.

Caroline Wilson, head at Ormiston Sudbury Academy, in Suffolk, says that she will face annual deficits over the next three years of more than £1.5 million if she continues to spend at current levels.

“We’ve tried to be savvy in what we do,” she says. “We’ve had a restructure with support staff, but we’re looking at teachers next year. We’re also looking at the curriculum, but quality won’t be affected.”

The school is one of 30 in the Ormiston academy chain, which is also taking steps to cut costs. It has saved £159,000 a year across its 19 academies by renegotiating energy bills and another annual £13,500 by streamlining printing contracts.

Toby Salt, chief executive of Ormiston Academies Trust, said: “Lots of people have criticisms about being a sponsored academy, but being in a family of schools means that we can get better value . . . and we will exploit [those avenues] relentlessly.

“We have challenging schools in poorly funded authorities but we’re having a non-hysterical response to the challenges they face.”

Its Sudbury academy is taking a proactive approach to cost-cutting. “We’ve joined teaching alliances and are now training students with a view to growing our own teachers,” Ms Wilson says.

“We have spent a lot of money on advertising but have struggled to recruit, applicants haven’t had the quality we look for.”

The school will also outsource continuing professional development sessions next year to raise extra income. “We are sustainable and will be open regardless of what is thrown at us. But it’s getting harder and we’ve got some tough decisions to make,” Ms Wilson says.

The Department for Education says, like all public sector employers, schools have to contribute more towards pensions to ensure costs can be met in the future.

But it will look carefully at the impact changes have when making plans for education spending next year.

“We are making sure schools are funded fairly so all pupils have access to a good education,” says a spokesperson for the department.

“This is priority for the government and a key part of our core mission to deliver real social justice.

“The last government made considerable progress in reforming the school funding system and we are protecting the schools budget, which will rise as pupil numbers increase.”

Mr Tomsett adds: “It’s bad, but we can do it. We can sort it out . . . But I genuinely don’t know what the solution is.”

But how has this impacted schools now? Here’s what the headteachers have already had to cut to balance their books…

Your thoughts