Internal support units inside mainstream schools risk serving as pupil “holding pens” that unintentionally reinforce cycles of exclusion, an education charity has warned.

According to a report by The Difference, a growing number of English schools are setting up internal alternative provision (IAP) for pupils struggling in the classroom, as they grapple with a “crisis of lost learning”.

An IAP aims to provide on-site support for pupils and reintegrate them into mainstream education. But the charity, which works to prevent exclusion in schools, said a lack of “clear guidance” means some are “unintentionally causing harm”.

According to the report, the expansion of IAPs is part of schools’ attempts to get a grip on record rates of exclusions, absences and an escalating number of children with special educational needs.

But there is little guidance on what good practice looks like, nor how many schools have such units.

The research points to the latest government figures, showing 93,700 (5.6%) more children were identified with special educational needs (SEN) last academic year, compared to the previous year.

This includes over 34,000 more children with social, emotional and mental health difficulties.

IAPs ‘now the norm’

“This shift is happening fast. Internal alternative provision is no longer the exception – it has become the norm.” said senior policy advisor at The Difference Cristín O’Brien, who co-authored the report.

Yet according to O’Brien, schools are often “navigating this important work in the dark”, adding: “Without the right support, there’s a risk they end up inadvertently creating an exclusionary space that can function a bit like a holding pen.”

John Pickett, head of Morpeth School in east London, set up its IAP The House in 2021 in a bid to take away some of the stigma surrounding offsite external provision. Yet there were not many examples around to draw on, he said.

Pickett set up the House, which usually has around six pupils and has been designed as a secure but also “celebratory” space, with teaching space, a kitchen dining room and outdoor areas.

Children attend for a range of reasons, Pickett explains, from those with health issues to those at risk of exclusion, including those who are “self-excluding” with severe attendance issues.

“We wanted to rid of the idea that this was a punishment, or somewhere you went where you were “naughty”.

Some of the challenges, according to Pickett, include the need for high-quality staff and being able to justify the financial cost in the current climate.

Sam Strickland is principal and CEO of The Duston School in Northamptonshire, which set up its own IAP in 2020. He said the units were becoming “not a luxury but a necessity” amid a growing number of children presenting as SEND and “behavioural drift”.

The increased demand coincides with a lack of available places in high-quality registered external alternative provision, says Strickland.

“With a backdrop of funding issues and a lack of Ofsted registered external alternative provision schools are caught between a rock and a hard place.”

Not a ‘dumping ground’

According to The Difference, the type of in-school support put in place for children at risk of exclusion in the past has ranged from short-stay “punitive spaces”, such as isolation rooms, to longer ‘remedial’ spaces such as behaviour support units.

In contrast, IAPs aim to provide high-quality teaching alongside attention to pupils’ social and emotional needs and are embedded in the mainstream school community.

According to The Difference’s best practice guidance, published today, IAPs should not be seen as a place to “fix” the child, and real success is more likely if provision is underpinned by “strong whole school inclusion”.

It has outlined four key tenets of effective IAP: that provision is “unified” with the mainstream school, it identifies and balances learning and wellbeing, and is “shaped by measurable pupil outcomes”.

Steve Howell, who runs Birmingham City Council’s Pupil Referral Unit and sits on the board of the National Organisation of Pupil Referral Units and Alternative Provision (PRUsAP) said the concern with IAPs is that they can become a form of “internal exclusion” where students are separated from mainstream peers as a way of avoiding permanent exclusion.

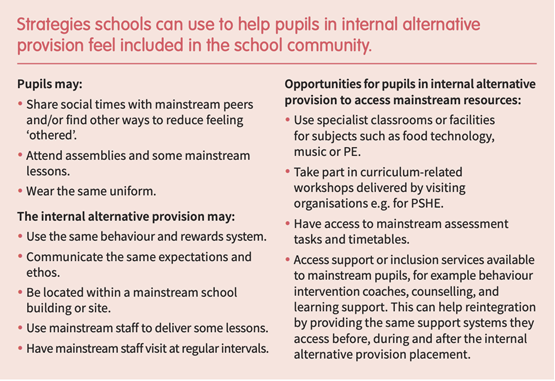

He backs the report’s call for schools to try and “unify” the main school with IAPs – with pupils sharing social times with mainstream peers, attending assemblies, and wearing the same uniform.

The study also recommends that IAPs need to be seen as “a place of support not sanction” which balances academic progress and wellbeing, rather than a “fluffy place” where no serious learning takes place.

Howell agreed IAPs had to provide much more than pastoral support. “I’ve seen some provision where children have a mentor and it becomes a space to sit and chat to an adult, but schools exist to educate,” he said.

Calls for more oversight

The report also urged schools to try and dispel the notion that IAP is a last chance saloon before exclusion, or a place for ‘naughty children’.

“The challenge for schools creating their own AP is to ensure that it does not become a dumping ground and that the culture of the AP is positive and aligned to the main school,” said Strickland.

While IAP is growing, there is currently no data on how many exist. Unlike other specialist units which require education health and care plans or high-needs funding, schools are not required to report their use.

Ofsted asks schools how many children it has in external AP, but not internal, according to Howell. He said there could be greater oversight and monitoring on how many children are attending IAPs, as well as a “detailed description” to define what the provision is.

Kiran Gill, CEO of The Difference (pictured right), said: “Schools are operating under crisis conditions, and many are responding with determination and innovation, developing internal alternative provisions to help keep children thriving in the mainstream.

“But too often, these efforts are unfolding without clear guidance, and despite best intentions, some risk replicating the very exclusions they aim to prevent, creating costly holding pens rather than inclusive support.”

Your thoughts