Each summer, more than a million youngsters across England sit their GCSEs and A-levels. It’s the culmination of years of schooling, and often shapes future education or career paths.

But what actually happens between an exam paper being handed in and a student receiving their final grade?

Schools Week explains all …

Pens at the ready: 16 million individual exams sat across 6 weeks

The most important thing to remember about exam grading is there’s *a lot*.

Last summer, 998,118 students sat GCSEs and 313,021 took A-levels. That means roughly 1,430 different exam papers were sat last year across 149 subjects – producing more than 16 million individual exam papers (known as scripts).

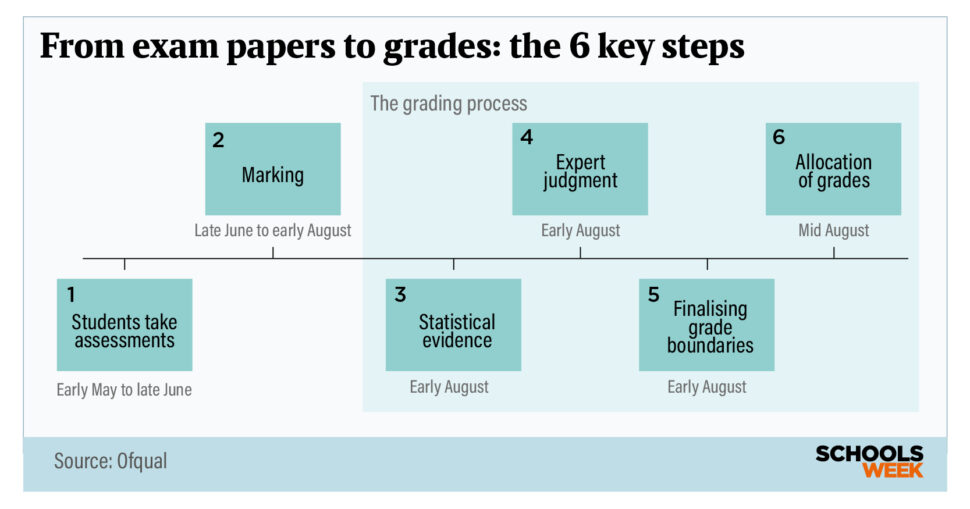

This all happens during ‘exam season’, which usually runs for around six weeks from early May to late June.

All in all, nearly 6,000 centres in England had exam questions delivered last year.

Staff must follow strict rules (known as ICE, instructions for conducting exams) which include signing for delivery of the papers as soon as they arrive and putting them in “secure storage immediately”.

Only authorised staff are allowed to handle materials, with no more than six people allowed a key to the storage facility.

But it doesn’t always go to plan. Last year, there were 70 security breaches reported – the most popular reason was for the wrong exam paper being opened.

On your marks: 70,000 examiners get to work

Once complete, the papers for each exam are normally posted straight away by schools to exam boards and held in huge warehouses.

Papers then have their spines removed and all answers are digitised on machines that can scan 4 million sheets an hour.

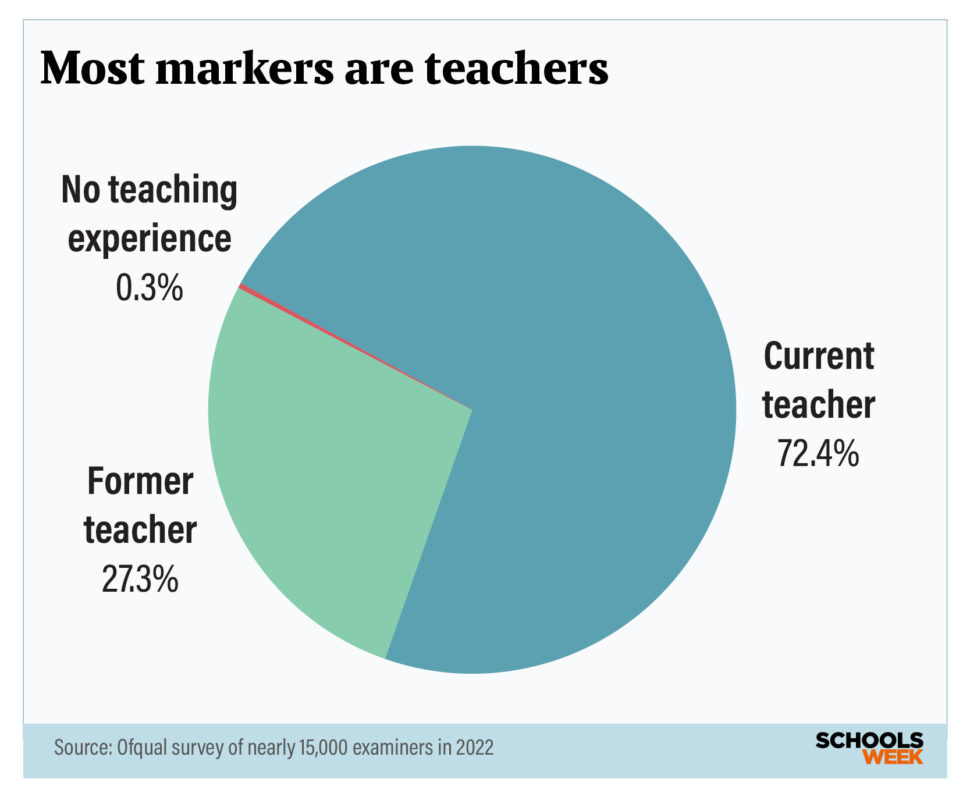

This allows exam boards to upload the answers to their marking platform so they can be accessed by the roughly 72,000 markers, nearly all of whom are current or retired teachers, between late June and early August.

A 2022 Ofqual survey of markers found they have on average 10 years’ examining experience and 20 years’ teaching experience. Their average age is 49.

Despite popular myths of coffee-stained scripts and red pen scribbles, nine in 10 examiners mark papers online, while just six per cent predominantly mark hard copies, Ofqual found.

Most choose to do it so they can better prepare pupils for exams, for extra money or to support professional development, the study added.

Rather than mark full papers, examiners typically handle individual questions.

An Ofqual study in 2014 found this can help reduce marking bias (what is known as the ‘halo effect’, where markers build preconceived ideas about a student’s ability based on their answers to previous unrelated questions).

Before marking, each examiner must also pass training and show they understand the mark scheme. But they are also tested in real time.

At random intervals, a ‘seed question’ – a question that has been pre-marked by a senior examiner – is thrown into the mix. If they deviate too far from the correct score, their ability to mark is frozen until they retrain.

In some exams, double marking is used – where two different examiners independently assess the same piece of work.

But how reliable is marking? Ofqual has studied how often a marker gives the same grade as a principal examiner (known as the ‘definitive’ or ‘true’ grade).

It found most grades were usually within one grade either way, which Ofqual says shows marking is generally consistent.

However, this depends a lot on the subject. Marking is less consistent in exams with essay-style questions.

For example, in maths – where answers are usually right or wrong – the ‘correct ‘definitive’ grade was given 96 times out of 100, according to a 2018 Ofqual study.

But in English language and literature – which involve more subjective, essay-style answers – the ‘definitive’ grade was given only about half the time.

But this leads to few grades being changed. Last year, just 2,655 of the 6.8 million grades awarded were appealed (0.04 per cent), with just 705 grades changed as a result (0.01 per cent).

Capulets, Montagues and misprints

There can also be errors made in exam papers. Last year, 97 per cent of questions were error free. But the number of mistakes across GCSE and A-level papers rose from 87 in 2023, to 100.

Sixty-five of these were errors in the content of question papers. But just 21 were identified prior to the exam, while seven were identified during exams and 37 spotted after exams.

Actions taken include issuing an ‘erratum’ – an instruction for an examiner to issue instructions to correct a mistake before pupils sit the exam – amending the mark scheme or replacing the paper.

Mistakes can be costly, too. One of the most publicised was exam board OCR mixing up Capulets and Montagues in a 2017 English literature question about Romeo and Juliet.

Nearly 3,000 students had to be awarded a mark based on their performance in other questions. Meanwhile OCR was fined £175,000 for the mistake.

Making the grade: the drawing of the boundaries

Once marking is completed, the baton is passed to grading teams for a process known as “awarding”. This is run by exam boards, but regulated by Ofqual.

Panels of four or five senior examiners, who are subject experts, convene between late June and early August to decide the minimum mark required to achieve each grade – known as grade boundaries.

This process aims to maintain standards over time – so that the same standard of work each year would get the same grade. (Note: this is a bone of contention in the sector, but this is not the same as ensuring the same proportion of students get a set grade, more of that later).

Grade boundaries are used because exam papers each year must produce questions that aren’t too predictable, test a range of knowledge, understanding and analytical skills and sometimes meet new rules – so they can vary in difficulty from year to year.

To achieve this, the panels look at statistical evidence and employ their expert examiner judgment. This includes looking at the prior attainment of the students taking the exam (for GCSEs this is typically key stage 2 results, and for A-levels this is GCSE results). Other data considered includes different characteristics of pupils sitting the exam and also how they performed on each question.

This analysis gives the panel a “starting point” which is then tested by examining the scripts close to grade boundaries – for instance two marks either way – against previous years. This process aims to ensure a certain grade this year is comparable to the standard from last year.

The panel discusses the findings, and it is the senior examiner’s job to reach a conclusion whether the proposed grade boundary credibly matches the standard of work.

If there’s disagreement, more analysis – such as looking at centre-level data – may follow. The outcomes are reported to Ofqual, with additional information sent if the process has been more complicated.

Fact check: is the results race fixed?

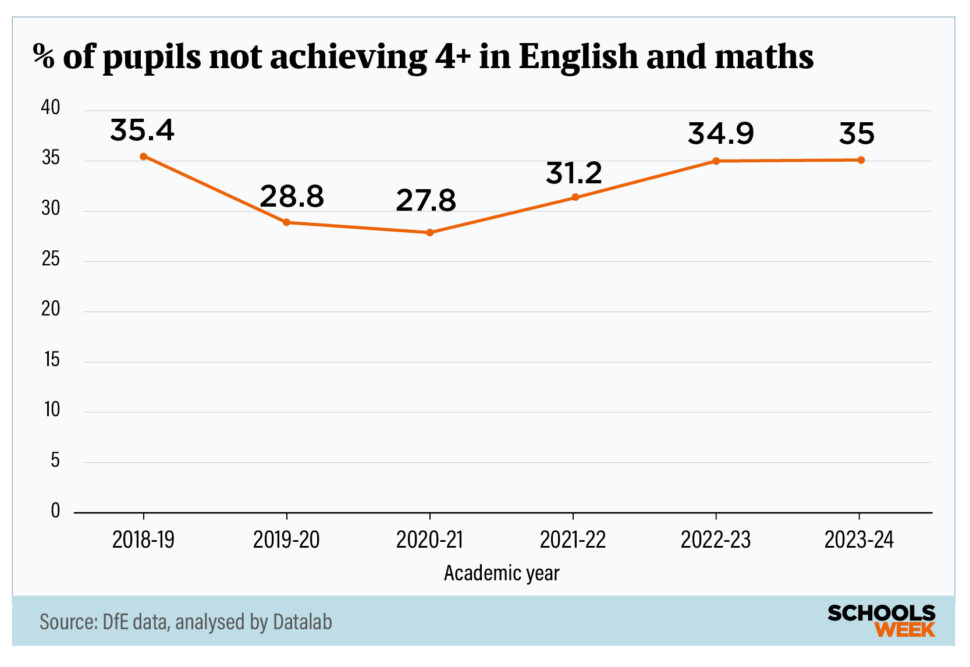

Many critics of the system argue there is a quota on grades. They say the system bakes in a ‘forgotten third’ – in reference to the number of pupils who fail to reach a grade 4 in English and maths (35 per cent last year).

But Ofqual says the grading process is not about maintaining a quota, or rationing grades – it’s about looking at the quality of work and ensuring consistency in standards.

Essentially, Ofqual says maintaining standards means it is no harder or easier to achieve a particular grade in each subject from one year to the next, and between one exam board and another.

“This is not about quotas of students,” said Sir Ian Bauckham, Ofqual’s chief regulator. “Each grade represents a certain standard of performance, regardless how many students reach that standard.”

The regulator also points out that GCSEs are designed to test the full ability range, with grade 1 technically a pass.

Ofqual adds the fact the number of top grades is relatively stable from year to year reflects the fact that student performance is typically relatively stable, too (not including the Covid years when exams were cancelled and teacher grades issued).

Overall, subjects with the most entries see the most stability in results, for instance English and maths. GCSEs also see less change in results across years because they are sat by whole cohorts of pupils.

There tends to be more fluctuation at A-level because there are a smaller number of pupils and the characteristics of those sitting them may change more each year.

Enter the National Reference Test

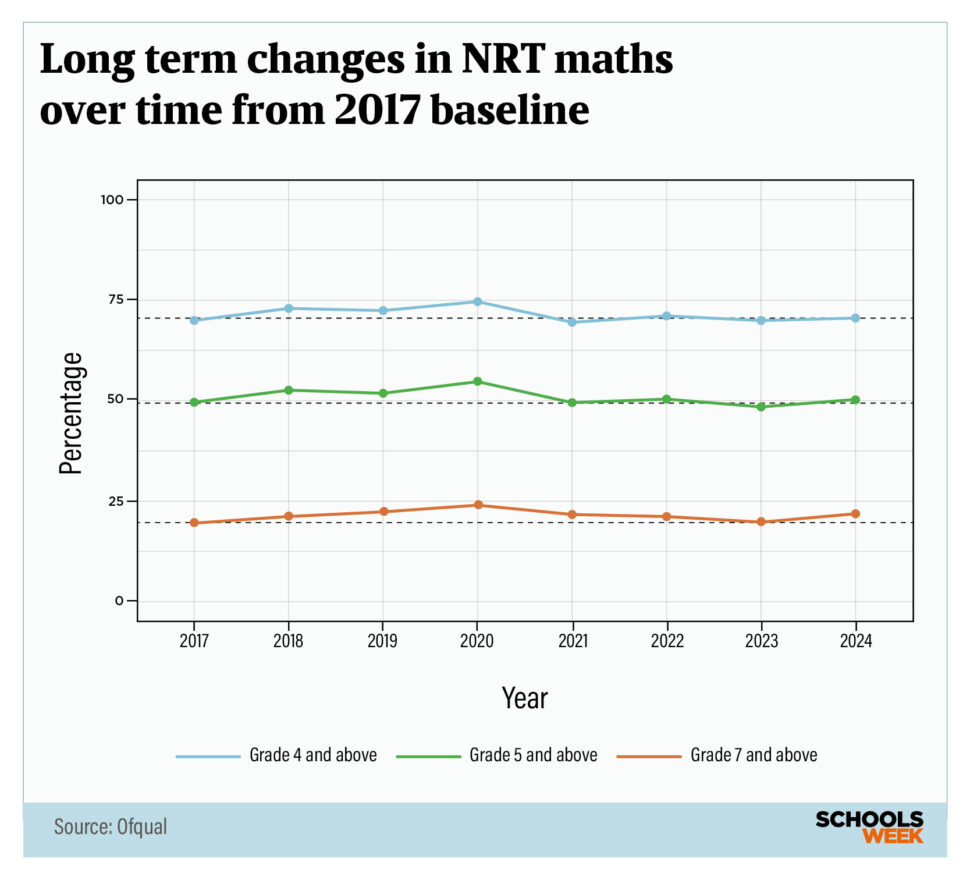

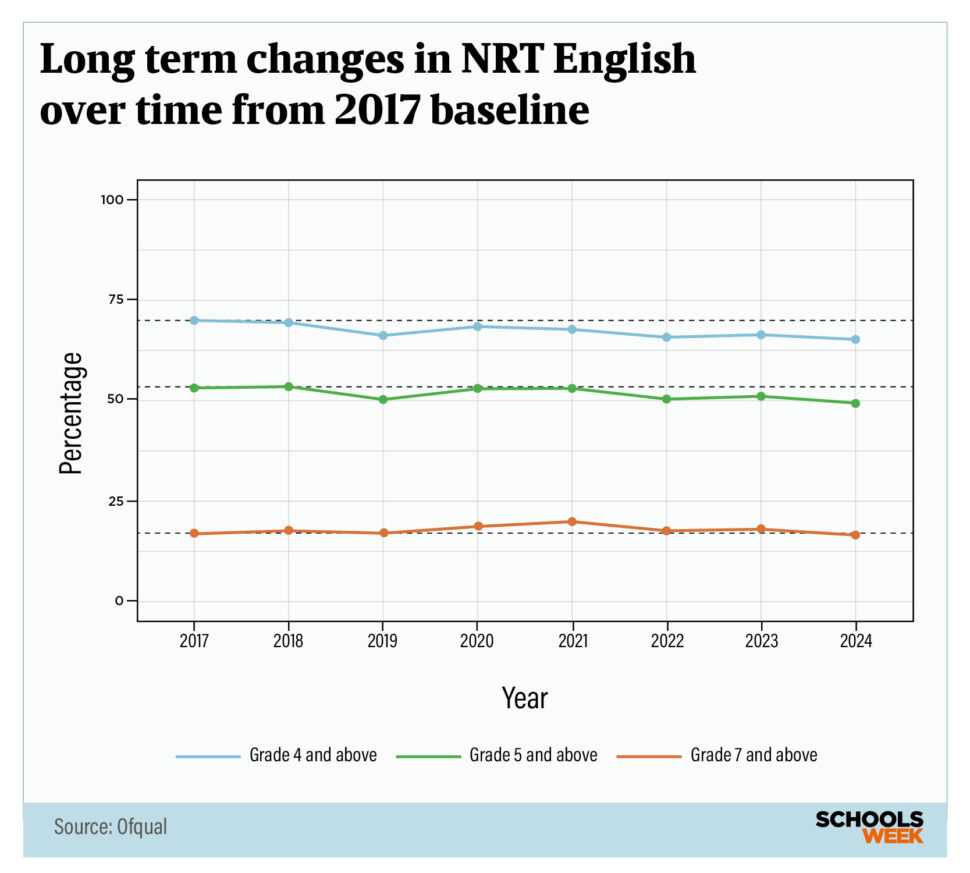

Ofqual also has a good way of checking if pupils are doing better or worse. Since 2017, Ofqual has run the National Reference Test each spring, where around 6,000 year 11 pupils from 300 schools take an English and maths test.

Chosen schools are required by law to do it, and students chosen are representative across demographics, centre type and geography. As questions are consistent, it eliminates the issue of tests being harder or easier across years.

Ofqual says it is the only form of external assessment that ran all the way through the pandemic, under the same conditions and in the same format, meaning it provides the “very best possible evidence of student attainment you can get”.

NRT results feed into the statistical evidence considered as part of the awarding process.

If the NRT shows an increase in a cohort’s attainment, or a decrease, this could result in adjusting grade boundaries. This is a decision that would be made by Ofqual. But, so far, this has never been used.

Ofqual said this was because, despite small changes in attainment noted between years, they want to see “clear trends” before acting.

“It’s not about tinkering, this wouldn’t support confidence in grading. We need to see clear trends before using it in the grading process,” an Ofqual spokesperson added.

The regulator was planning to use the NRT to up maths results in 2020, after a rise in attainment for three years running at grades 7 and above, but Covid struck and exams were cancelled.

Last year, the NRT started to show more students achieving a grade 7 or above in maths, and a possible reduction in students achieving a grade 4 in English.

This year’s results will help understand if there is a clear trend, which could lead to changes.

The results ceremony: jumping for joy (or despair)

Once grades are awarded, exam boards send them to schools’ management information systems the day before results days.

This year, GCSE results day is on Thursday August 21, and A-levels are on Thursday August 14.

Results can’t be shared with pupils until 8am, so pupils – most of whom head into school to pick up their results – can get support from staff if needs be.

But the time-honoured tradition may be about to change. Nearly 100,000 year 11 pupils in Greater Manchester and the West Midlands will get their GCSE results through a government app this year as part of a trial ministers hope can save schools and colleges £30 million in admin costs.

This would predominantly save money by allowing pupils to enrol on further education courses without needing to bring physical copies of their qualifications. But pupils can still attend schools to pick up their results if they wish.

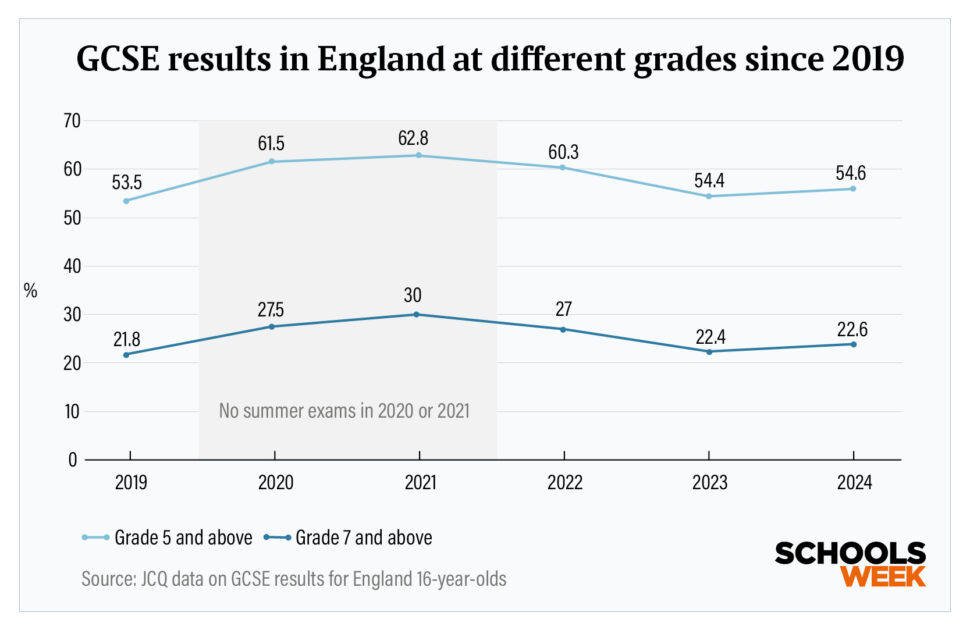

It’s been a rocky ride for results. Results soared in 2020 and 2021 after exams were cancelled because of Covid and teacher grades were awarded.

Ofqual then gradually reduced grades across the next two years to get standards back to the pre-pandemic norm in 2023.

What next for exams? Reviews, AI and going digital

Despite regular calls for exams to be scrapped, the two years of using teacher grades during the pandemic instead do not appear to have strengthened critics’ case.

Bauckham previously told Schools Week the Covid disruption showed “the value of having fit-for-purpose external assessment to preserve the reputation of those qualifications”.

Labour is, however, in the middle of a curriculum and assessment review, due to be published in the autumn term. But it has promised “evolution, not revolution”.

And the review’s interim report stated “we are clear that traditional examined assessment should remain the primary means of assessment across GCSEs”.

However the review is looking at whether they can “reduce the overall volume of assessment” at key stage 4.

Data for last year shows more than 40 per cent of 16-year-olds took 9 or more GCSEs.

Elsewhere, exam boards are all developing on-screen exams – but plans have been delayed and Ofqual is investigating the feasibility of this amid concerns schools do not have adequate technology.

However, there is also a climate change element to moving exams online. An Ofqual study found the carbon footprint of a single student sitting a GCSE English language in 2022 was the equivalent to driving 1.8 km in a petrol car, or more than five wash cycles at 60 degrees Celsius.

The regulator is also investigating the potential for AI to undermine coursework, and whether it can be utilised to improve marking and grading.

Your thoughts