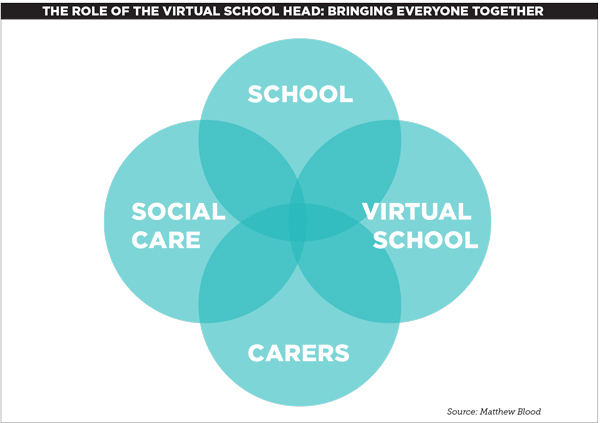

Everyone needs a pushy parent, so why should looked-after children (LAC) be any different? That was the question Matthew Blood, the virtual school head for three West London boroughs, posed at Optimus Education’s conference in Birmingham last month.

Blood presented a mixed picture on how well LAC are performing in schools. He, like other virtual school heads (VSHs) across the country, is responsible for improving the educational attainment of such children. The role is reasonably new but is now starting to bed down within local authorities. Their challenge is to champion the education of LAC in the authority’s care as if those children all attended the same school.

But how can VSHs work effectively within a complex multi-agency environment to improve outcomes? And how do they make best use of Pupil Premium Plus – the £1,900 they are allocated to help support each pupil in care at school?

With just 12 per cent of LAC achieving five A*-C grades including English and maths at 16, the scale of the task is huge. It is also well known – but worth repeating – that two-thirds of LAC have a special educational need and only half have emotional and behavioural health that is considered normal.

While there is evidence of improving educational progress for children and for the positive impact of the virtual schools, Blood admitted the gap between LAC’s attainment and that of all children remains wide.

A major problem in the role of the VSH is “a lack of evidence base about what works” for young people in care, meaning money is sometimes thrown at the group without any real way of knowing if it makes a difference. He said schools “do not have sufficient understanding… and they say that the children present too many challenges.”

Blood said schools have to ask themselves: “What do you think it’s like being a LAC at your school? They are a unique group, and it’s important schools understand the impact of trauma and attachment difficulties.

“How is that going to impact on their learning? Schools can rebuild those relationships and enable them to be ready for learning.”

The factors that make a difference to LAC include their school having high aspirations, a holistic approach to planning and support, regular contact between home and school, and a readiness to listen to both the pupil and their carers.

Blood also said VSHs need to quality assure statutory Personal Education Plans (PEPs, see opposite page) – the school-based meeting to plan for the education of a child – to ensure a focus on outcomes.

Luke Rodgers (pictured top), who grew up in care, described the challenges further. As founder and director of Foster Focus, he delivers training to foster care professionals and gives care leavers opportunities to share their stories.

The 24 year old, who won Unltd’s Young Social Entrepreneur of the Year award in 2014, spoke out about his experiences as a LAC in school. He said PEPs were “nearly always a turning off of the child”. And added: “Why do we need to sit round a table and make the young person feel dreadful?”

While at schools he received lists of negative comments – which he then “positively reframed”. He added: “I did not think anyone expected me to achieve.”

He also drew attention to a lack of support for LAC once they leave school at 16 and go to college.

Alun Rees, a consultant to the University of Oxford’s department of education and author of the Virtual School handbook, due to be published this week, argues schools can find “gold standard” strategies for improving progress and attainment if they look in the right places.

He noted that Ofsted are increasingly using outcomes data to see what is effective for LAC and argued that without a clear narrative for how their Pupil Premium Plus is helping a child, a school would struggle to convince Ofsted it was working well. Robustly monitoring the premium’s use is therefore vital.

Rees recommended a tracking system for Pupil Premium Plus spending that is easy to use and integrate into normal practice and which draws together child and cohort data for easy comparison.

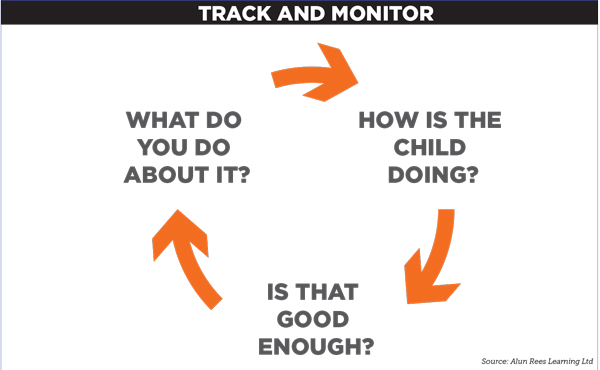

Tracking and monitoring should also ask how the child is doing.

“Is that good enough compared to their potential?” continued Rees. “If not, what will the school or virtual school do about it?

“There must be regular comparison of how the child is currently doing with how they are expected to achieve, and, when choosing which intervention to use, schools and virtual schools must think about how strong the evidence is that it will work.

“It is also important to remember that how an intervention is delivered, by whom, and how well prepared they are, can matter a lot.”

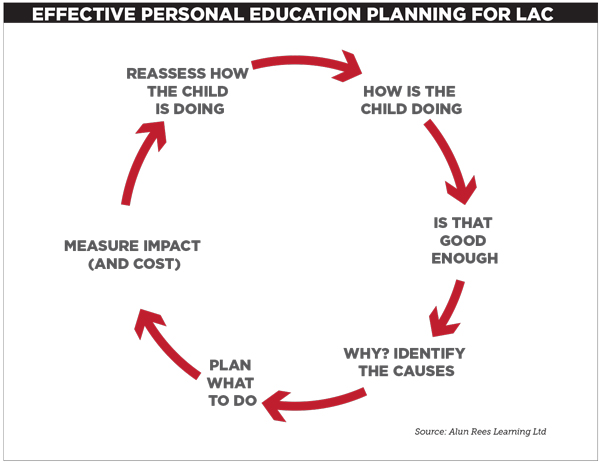

He said that it is also important for people to understand why interventions don’t work. If, for example, a child’s literacy is “stuck”, he said, “is it due to cognitive issues, gaps in earlier learning, or something else?”

When it comes to selecting interventions that will have a positive effect, Rees said leaders should look at those which have been included in randomly controlled trials, systematic reviews and had strong statistical correlations.

Teaching school alliances have a core research and development strand and could be approached to validate interventions, he added.

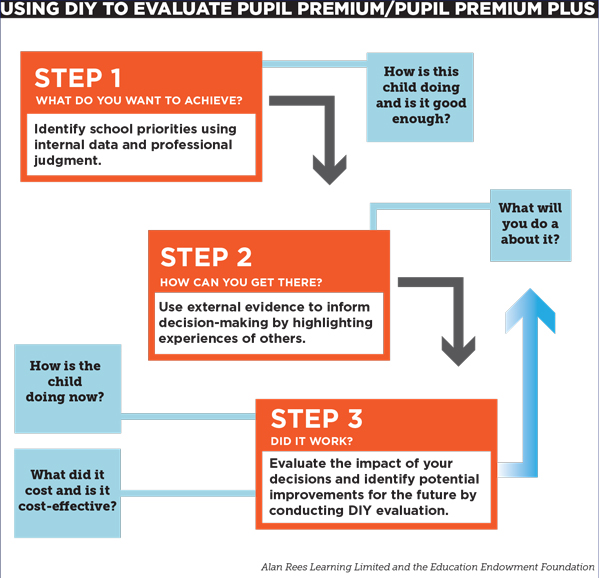

He recommended using the Education Endowment Foundation’s DIY Evaluation Guide as a way of evaluating Pupil Premium (and Pupil Premium Plus) spending. Presenting school improvement as a cycle, he said the process could also be reflected at the level of an individual child so that the school and the team supporting the child can map how both school and student are doing (see box right).

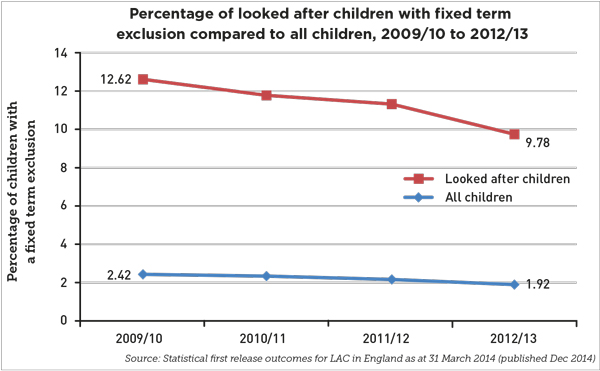

Children in care are twice as likely as all children to be permanently excluded and five times more likely (10 per cent of LAC) to have a fixed term exclusion (see above right). Rees said excluding LAC from school disrupted their learning and led to diminished progress as well as damaged relationships. He also said they were a key line of enquiry that an inspector might pick up.

The solution, said Rees, is to focus on balancing support with rigour (see above). He believes the key is to deliver increasing support through encouragement and nurturing – to work with pupils in a restorative way to deliver effective and lasting change. His message is clear: punitive and authoritarian approaches do not deliver sustainable change.

The Virtual Schools Handbook is due to be published this week at www.reescentre.education.ox.ac.uk/about-us/visiting-practitioners/virtual-school-head-handbook/

Optimus Education helps school leaders to manage staff development and drive whole school improvement.

What does the evidence tell us works to improve educational outcomes for looked-after children (LAC) in schools?

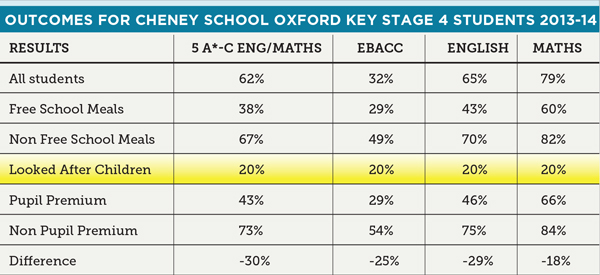

Amjad Ali is an assistant headteacher at the 1,400 pupil Cheney School in Oxford, with the role of supporting any student who has additional needs. Only 20 per cent of looked-after children at his school got five A*-C GCSEs in 2013-14 (see above): “We do well – but not well enough,” he said.

Thirty-five per cent of pupils at his “very diverse” school with “lots of unaccompanied asylum seekers” were entitled to free school meals in 2014, against a national average of 28.5 per cent.

While there are “no quick wins”, he argued that attainment is “the best therapy and nothing is better for a disadvantaged student”. He also

believes a whole school approach is absolutely vital.

Mr Ali emphasised the importance of effectively including all pupils in high-quality everyday teaching. The school also has an LAC lead, who gives pastoral and academic support to all looked-after children, and an academic mentor in each year group to provide focused support and to aim to raise attainment.

Whole school strategies include a consistent approach to teaching and learning, and a focus on continuous professional development for teachers. Mr Ali said other targeted strategies include one-to-one support, “catch-up” provision, and rigorous monitoring of the impact of targeted interventions.

But he stressed that based on his school’s experience, “complete one-to-one work” with LAC had not worked – and neither had “rewards without targets, not following behaviour policies and not involving all agencies”.

Lucy Wawrzyniak is team manager for the Virtual School for LAC in Oxfordshire and is reviewing the evidence on what improves outcomes.

Findings include a number of studies highlighting one-to-one tuition as a positive intervention. She also said reading at home with foster parents has a positive impact on outcomes, and that the aspiration of the caregiver has the most positive impact of all on a child’s outcomes. Reducing exclusions also increased educational outcomes.

She said that no child is able to respond to intervention unless their basic needs are met at home.

Ms Wawrzyniak is now collating a toolkit of research to help design interventions and share examples of those tried so far. She is using the Education Endowment Foundation DIY Intervention toolkit as a base as well as findings from the Rees Centre for Research into Fostering and Education and access to broader educational studies.

She also flagged up the Oxfordshire Caremark – an audit tool awarded to schools if they meet requirements across seven strands: barriers faced by LAC young people’s voice, success, progress, learning and teaching, multi-agency planning and governance.

To contribute to the toolkit send examples of interventions to lucy.wawrzyniak@oxfordshire.gov.uk

Your thoughts