Headteachers are taking to Twitter as part of a campaign to expose as false the government’s claim that school funding is protected.

While the government has pledged to maintain per-pupil income, heads currently preparing next year’s budgets are having to factor in rising costs such as increased pension and national insurance contributions.

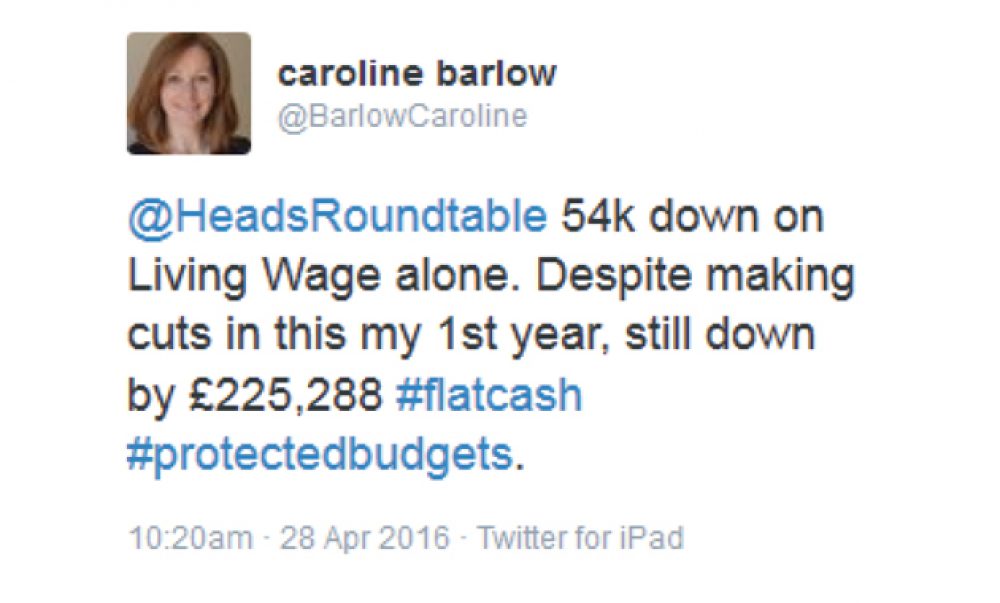

Now they are using the hashtag #FlatCash to reveal the reality of their funding.

Liam Collins from East Sussex (pictured), one of the heads who started the campaign, said 13 schools that responded in the past few weeks have been forced to slash a combined total of more than £1.5 million from their budgets.

“Some schools will be able to weather that for a year, using a surplus, before having to take action.

“When 80 per cent of your costs are staffing, there is only one area that a school can look at to control its costs. Turning lights off will not bring the levels of saving required.”

Collins, head of Uplands community college, started the ball rolling by posting that he will have £183,703 less to spend on pupils next year.

Caroline Barlow (pictured), head of nearby Heathfield community college, then tweeted that she has had to slash £225,288 from her budget – and urged colleagues to share

their losses.

Ministers maintain they have protected funding by ensuring the cash per-pupil it hands to schools remains static.

But Barlow said the recent rise in the national living wage means she has lost £54,000 from next year’s budget – which would pay two teachers.

Collins said many schools have also reported losses from their deprivation funding after the English Indices of Deprivation – which charts

the poorest areas in the country – was updated in September.

Added to the increased pension and national insurance contributions, Collins said heads now faced “difficult conversations” with staff and parents over cuts.

He said he wants the public to understand the “honest” reality that school budgets are being cut.

John Tomsett, head of Huntington School in York, tweeted that if his school’s budget had kept up with inflation since 2010, it would have an extra £800,000 next year.

Schools Week revealed last year how Tomsett had already slashed £350,000 from his school’s spend.

Vic Goddard, head at Passmores Academy in Essex, also posted that his school had £280,000 less for next year.

Barlow said heads were facing “pretty stark choices”. “There isn’t a single one that does not have an impact on children.”

But she added: “Ultimately, I think

the profession will show itself to be determinedly focused on providing the best possible solutions for young people and our staff. I can already see people starting to

work together to share ideas and find creative solutions.”

A DfE spokesperson said: “We have protected the overall core schools budget in real terms, so that as pupil numbers increase, so will the amount of money in our schools.

“We are making funding fairer by consulting on proposals for a new national funding formula so that areas with the highest need attract the most funding and we are continuing the pupil premium – worth £2.5 billion this year – giving schools significant extra funding to raise the attainment of disadvantaged pupils.”

This is an incredibly complex and emotive subject with both sides it seems to me using selective reporting to make their case.

It is a simple fact that since 2011, education funding has been flat cash per pupil. That basic funding is massively unfair with deprivation and inner-city-challenge obsessions of politicians of all shades pushing funding disproportionately into highly populated areas where they think they can buy most votes.

The much vaunted Pupil Premium is just the latest example of this. It has not stayed flat. It has grown fairly steadily until it now stands at £2.5B, largely going to the already relatively well funded urban areas. However, the Pupil Premium is monitored so Ofsted has a good idea about the effect of this extra funding.

What is much less widely reported is that the deprivation funding in the main formula (the DSG) is also about £2.5B. Ofsted doesn’t have the slightest idea where a single penny of this money goes because it is not required to look. There’s a very good chance that as schools receive ring-fenced (monitored) PP that it releases other deprivation funds for other purposes. I’ve often wondered if we could have “closed the deprivation gap” by a similar amount by simply monitoring the existing £2.5B and used the new money for something else. Early Years funding is even more distorted that schools funding with areas like Camden getting 3x as much money per pupil as rural counties like Worcestershire or Solihull. £2.5B could have introduced fair funding into early years almost overnight and would have been utterly transformative.

In a ridiculously simplistic, hypothetical scenario where all the variables stay the same year to year, we are not talking about actual cuts in funding but an increasing affordability gap as costs increase and income stays flat. If funds are actually falling then other factors are in play, falling pupil numbers, changes to deprivation factors, changes to prior attainment. Each of these is an interesting topic in their own right. Schools can talk about cuts in real terms and that’s a reasonable case but a hard one to answer in austere times when other areas of national spend are seeing actual cuts. But if schools talk about cuts in actual terms as they appear to do in this article without discussing the variables causing the losses, the government will just duck behind its flat cash defence and we’ll get nowhere.

Pupil numbers are a massive variable in school funding. If school reputation takes a knock for whatever reason, then it can have a dramatic impact on pupil numbers and school funding often fuelling a self-supporting crisis. That’s just life in Education. But what if a bright spark opens a new free school in an area that doesn’t need extra capacity? We used to have a coherent local plan where the LA was responsible for pupil capacity and managing capital development to meet the need. The government has created an unholy mess giving RSCs authority to open new schools but without the responsibility for the consequences leaving a broken LA model with responsibility without authority. Just one area where the government needs to be held accountable and a U-turn is desperately needed.

If funds are actually falling in a school and pupil numbers are solid, then it might be down to a changing deprivation profile as the article suggests. The main formula has a deprivation factor that all LAs are supposed to use (IDACI). The data behind the factor changes every 5 years, 2015-16 being a new period. The change was significant as deprivation profiles of postcode areas are subject to dramatic change over time. LAs can set their own factor values so a County that makes heavy use of IDACI will see many winners and losers even if it maintains its funding values. You’ll notice that we don’t hear from the winners so we aren’t presented a balanced view. We have to look at the big picture and get into the detail if we are to find a path to more stable funding.

Prior attainment is another variable and another where the government does not have clean hands. The results of Primary SATs determine whether or not a pupil is a “low achiever” a they enter Secondary school. Two years ago the government changed the criteria so that a pupil needed to achieve in English AND Maths rather than English OR Maths. In Worcestershire that doubled the LPA pot for Secondary Schools

because our LPA factor was nearly 3x the national average. The next year all schools voted to adopt minimum national averages for all factors. Worcs schools have had a roller coaster ride re LPA but we are we have already effectively embraced a national formula so we have absorbed our turbulence early. But the LPA story is far from over because the government is still fiddling with SATs and EY measures. In a flat funded system, even with stable pupil numbers, policy change creates winners and losers. Again, if want to see some stability then we have to debate the issues. If both sides just keep going for the big headline statements, then we won’t get anywhere because the devil (and the solution) is in the detail.