An exodus of looked-after children from the capital could be driving down the achievement rates in other parts of the country, a new Schools Week analysis has found.

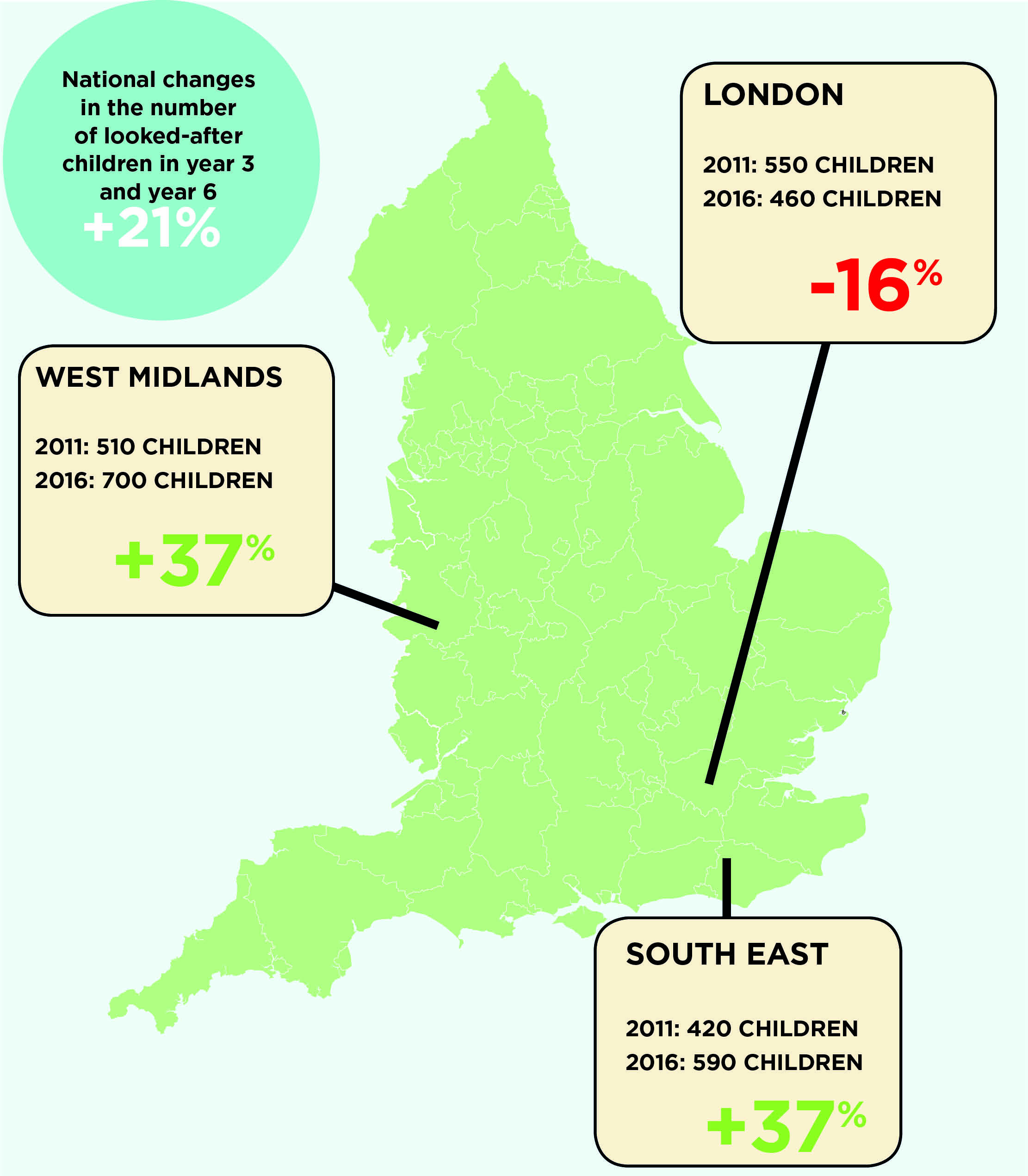

The number of primary-aged children in care nationally has risen 21 per cent since 2011, but during the same period numbers in London dropped by 16 per cent.

Overall, the number of secondary-aged looked-after children has dipped by 3 per cent – largely due to falling numbers of teenagers – but there was a much bigger 13 per cent fall in the capital.

The figures only relate, in all examples, to children in exam year groups – year 3, year 6 and year 11 – as these are the figures released in the government’s official statistics.

Areas that appear to be increasing most rapidly in primary include the West Midlands, which has risen by 37 per cent from 510 in 2011 to 700 children in 2016. The southeast (excluding London) has also increased by the same percentage from 430 in 2011 to 590 in 2016.

Wolverhampton was particularly hard hit with a 275 per cent increase in primary-aged children during this time and a 75 per cent hike at secondary.

London was the only region with a decrease in primary-aged looked-after children over the period.

Experts say the drop in London’s numbers are the result of fosterers priced out of the capital, councils not being able to fund children’s homes in the region, and moves to protect children from gang culture.

They also believe that children in care, who statistically have considerably lower attainment scores than their peers, could be lowering the published outcomes of primary schools in the areas where numbers have dramatically increased.

However, they say that the number of looked-after children moving from London is “too small” to impact on secondary schools with bigger cohorts.

The attainment gap between children in care and their peers has narrowed since 2010, but still remains substantial. In 2010, 12.4 per cent achieved the benchmark of five or more A* to C grades, including English and maths, compared with 52.9 per cent of other pupils – a 40 per cent gap.

That gap decreased a little by 2016, when 13.6 per cent of looked-after children achieved the standard compared with 53 per cent nationally, but the two figures remain stubbornly far apart.

Few potential foster parents can afford a house with a spare room

Malcolm Trobe, deputy general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, warned that an increase of just two looked-after children in a primary cohort of 30 youngsters “can have a big impact on overall results if they are low-achieving” given the pupils will contribute 6 per cent of results.

In secondary schools, however, two pupils in a cohort of 200 “would not influence results” overalls.

Schools Week analysed new government figures on the educational outcomes of children in care for at least 12 months and found that since 2011, the number of children in care in year 3 (age 7) has increased by 15 per cent and the number in care by year 6 (age 11) has increased by 26 per cent, with much of the change due to increased pupil numbers overall.

But in London, the figures went down by 20 per cent for year 3 and down by 14 per cent for year 6.

Meanwhile, the number of looked-after children in year 11 (age 16) dropped by 3 per cent overall – again related to a change in the overall cohort size.

But London had a much bigger drop of 13 per cent.

Emmanuel Akpan-Inwang, director of The Lighthouse Project, a group that is establishing a new model of children’s home in London, said there were “several reasons” why the number of looked-after children in London has fallen, including high living costs.

He told Schools Week: “Few potential foster parents can afford a house with a spare room.

“Another factor is the challenge of establishing children’s homes in London, which is much more expensive than in other parts of the country. Local authorities with downward pressure on their budgets are more likely to place young people outside the capital.”

Chloë Cockett, policy manager at the care leavers’ charity, Become, said that children in the capital might also be moved out “to keep them safe if they are victims of child sexual exploitation or have been involved in gangs”.

London has been lauded as a high-achieving area in recent years, particularly for poorer children.

However, if vulnerable and statistically lower-attaining groups are decreasing in its boroughs while increasing elsewhere, it could be that the shift in demographics in London is boosting results.

Trobe said that while a number of factors contributed to London’s success, it was “too difficult” to isolate a single factor such as children leaving the capital.

Akpan-Inwang added that the number of children involved in the care system was “too small for there to be any identifiable impact on school improvement”.

How do the changes and timescale relate to the introduction of the “spare bedroom tax”? Has there been a differential increase in adoption comparing different local authorities?