When men become heads of their schools, they receive a pay rise of roughly £8,000. For women that figure is just shy of £6,000.

The government are working flat out to hire graduates with physics degrees – paying as much as £50,000 for them to train. Yet dig into the data and you will find no relationship between highly-qualified physics teachers and the average GCSE point score of pupils in science.

Statistics like these show the importance of data in education and how it should help navigate policy decisions.

Yet the numbers are all too often ignored. This is one reason why the Education Datalab, headed by Dr Rebecca Allen and launched on Wednesday night at an event presented by Newsnight’s Chris Cook (both pictured), used the National Pupil Database and the School Workforce Census, to gather seven nuggets of information, which it hopes will inform teachers, school leaders and policymakers.

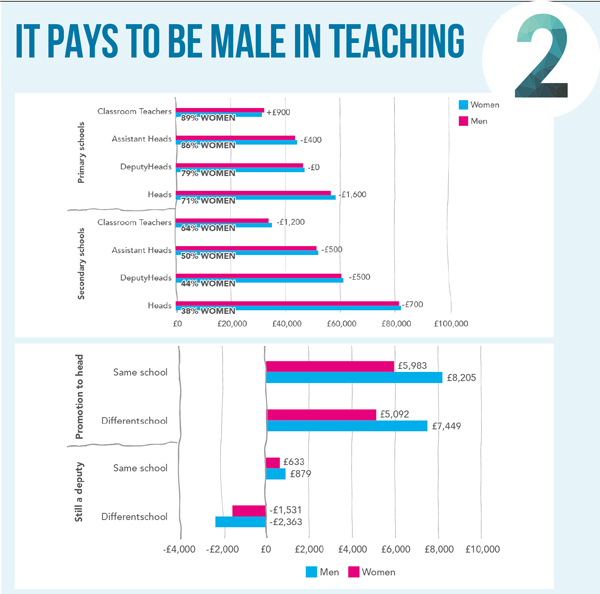

On the matter of women’s pay, the discrepancy is shocking. Women dominate the teaching workforce, at all levels. Yet Datalab’s research shows men are more likely to succeed in external appointments for headship.

When a male candidate is promoted to headteacher at the school where he works, he receives, on average, an £8,205 pay increase. Women in the same position would get £5,983. The man’s raise would be smaller if he were switching to a different school, but still greater than that of a female counterpart doing the same thing.

The only time a male candidate takes a larger pay cut than a woman, in senior positions, is if he remains as a deputy headteacher but moves to a different school. In this instance his pay would decrease by more than £2,300; hers would fall by £1,500.

Education Datalab suggests this could be due to men moving out from London more often – losing the extra allowance they receive for working in the capital. It also theorises that the higher wage for men could be attributed to them being more likely to take headships at more complex schools, or more risky headships.

But Dr Allen (pictured) also wonders whether there is an unconscious bias from interview panels – which are primarily governing bodies – towards male applicants.

She said: “Our findings need to be the start of a conversation about why women successfully achieve internal promotion to head from a deputy headship at the school and yet do not achieve promotion at different schools.”

Read more from Dr Allen and Education Datalab in tomorrow’s edition of Schools Week

7 Education Ideas presented by Education Datalab

Yes. But how will depend on where you are. Local authorities in the north are predicted to see “sharp” rises in progress, including consistently low-performing areas like Blackpool, Knowsley and the Isle of Wight.

Knowsley, the worst performing area for GCSE results this year under the current five A*-C including English and maths benchmark, could make an 11 percentage point rise in its results by just “filling the slots” in its curriculum.

Authorities in London will continue to perform well under the new accountability measures. However, unlike in the north, further progress in the capital and the rest of the south will require improvements in attainment as well as curriculum.

That it does, despite men being in the minority. The analysis attempts to challenge the “well-versed” reasons that are given for women slipping behind in pay – primarily the impact of childcare.

Men working in senior positions get, on average, £87 to £389 better annual pay rises than women in the same roles.

And men are more likely to be offered a senior position for an external post, whereas women are more likely to get promoted internally.

When men are offered headships within the same school, their pay is more than £2,000 higher than a woman offered the same job within the same school, similarly when they move to a different school

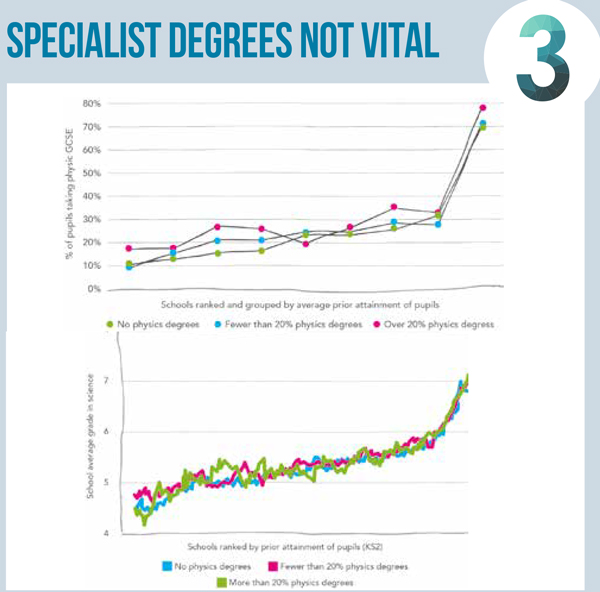

Ministers have pushed the message that not enough physics graduates are taking up teaching positions.

But does a graduate teaching this subject equal better outcomes for the pupils?

It appears not. The data shows little variation in attainment or take up of physics based on whether a teacher has a degree in the subject.

Education Datalab’s report asks: “Do specialist physics teachers encourage GCSE physics take-up, or do high triple-science entry levels attract specialist physics teachers to apply to teach at the school and does the school need to work harder to recruit them?”

By entering children in receipt of the pupil premium in for more qualifications, the Attainment 8 measure will show the narrowing of the “gap” between such students and their peers more quickly.

It says that many pupil premium children are often low-achieving which makes it harder for them to achieve a C rather than a D, and ignores any substantial progress they have made throughout their schooling.

Education Datalab’s analysis shows that the change in how progress is measured will see this gap close within decades, perhaps by 2032, rather than in 250 years under the current benchmark.

Education Datalab suggest that secondary schools often claim that primary schools inflate pupils’ grades at Key Stage Two.

However, it seems people should be more worried about the deflation of Key Stage One baseline scores. Schools may be doing this so they can show more progress by the time pupils have finished Key Stage Two.

Given the decisions headteachers will be making in the coming months over who to pick for the reception baseline tests, this is an important issue to take note of.

Children do not take an obvious course in their learning. They will often underperform or outperform expectations formed by teachers on the basis of their Key Stage One attainment.

The report found that only nine per cent of pupils take the “expected” pathways through key stages two, three and four. And the model to accurately predict a pupil’s attainment falls even further in secondary schools.

As a measure to assess progress in the classroom by Ofsted and by senior leaders, the analysis believes such tracking systems need to be used carefully as the way children learn is too “idiosyncratic”.

Is passing the 11+ a good indicator of academic success later in school life? In some cases, it appears not.

The analysis shows that those children who just pass the 11+, on average, perform worse than their primary school peers who just miss out on getting that place at the grammar school.

These “lowest passers” struggle against the rest of their grammar school peers, Education Datalab argues.

The evidence shows the “highest failers” outperform in attainment and GCSE English and maths, and take more qualifications, yet fewer GCSEs.

The “highest failers” are also twice as likely to be eligible for free school meals than the lowest passers.

Your thoughts