From September, schools will need to inform the government of each child’s country of birth, nationality and their level of proficiency in English if it is not their first language.

Almost one in five (1.25 million) children in England are classed as having English as an additional language, but current data about their performance is mixed, and does not provide an accurate picture.

The government believes gathering more detailed information will help to target resources.

Sophie Scott looks at the measures, and weighs their pros and cons.

A system designed for Welsh schools to assess their pupils’ skills in English will be used by schools in England from September to decide the proficiency levels of pupils who speak a different language at home.

More controversially, schools will also need to record the country of birth and nationality for every pupil — regardless of their language.

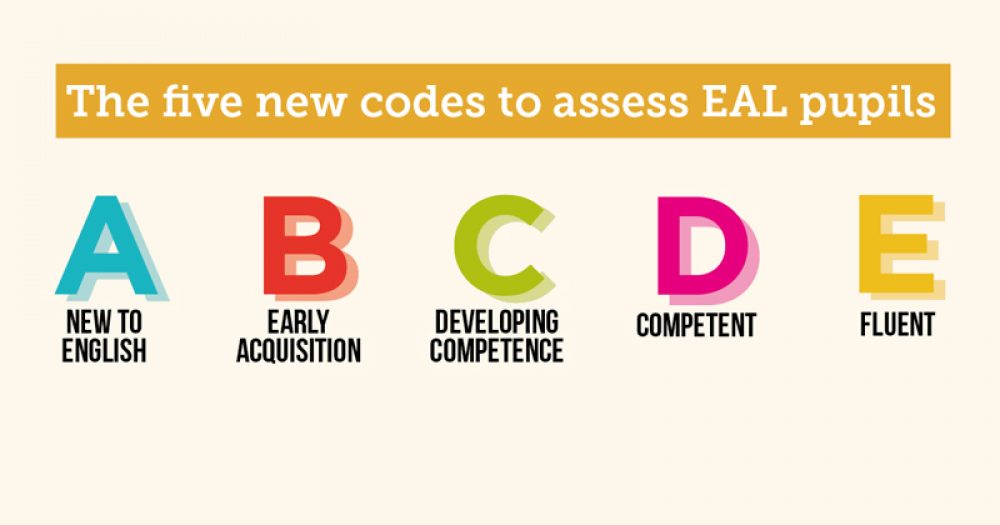

At present, schools in England only record if a pupil speaks English as an additional language (EAL) or not. From September, they will need to assess each EAL pupil’s “proficiency level” using a new five-point scale (see box right), which ranges from A at the bottom and E at the top. This will be passed to the government for analysis.

Each pupil will receive just one grade for their EAL level, combining their reading, written and spoken language proficiency.

We shouldn’t hand over children’s entire histories for fuzzy purposes

As Adam Medlycott, a researcher at The Key, explains: “Schools will need to assess the position of pupils with EAL against a five-point scale, making a ‘best fit’ judgment.

“They will not be required to use a specific form of internal assessment but should use the scale to make a judgment that corresponds to their own assessment system.”

Currently, analysis of EAL pupil performance is binary. A child taking SATs at primary school with only basic comprehension can be in the same category as a child who speaks English fluently, simply because they both speak another language at home.

Sameena Choudry, founder of Equitable Education, which offers consultancy on reducing achievement gaps between ethnic groups, says: “EAL pupils are not homogenous. You could be comparing a fully bilingual child, daughter of a German banker, with somebody who has just come from the Czech Republic with a Roma background, or a second or third generation child where another language is spoken in the house.”

In the documentation explaining the change to data collection, the Department for Education (DfE) says having more information will allow it to provide “important national statistics on the characteristics of this group, along with their attainment and destinations”.

But, while there is a consensus among EAL professionals that the data is important, there are extensive concerns about how the records will be collected and used.

Graham Smith, managing director of the EAL Academy, is worried by the lack of training for teachers in measuring pupils’ language abilities and whether judgments will be consistent.

“The government is providing no support, so it’s then up to local authorities, academy chains, and schools to try to bring some consistency.”

Even in areas where more training is available, it is not always teachers who submit the information into the school data system.

Di Leedham , an EAL specialist, said many schools did not have up-to-date data systems meaning some languages weren’t available to select.

“One of the highest numbers of EAL languages is ‘not known’,” she said. “Not always because they are not known, just that the school doesn’t have an option for Bulgarian, say.”

Given EAL co-ordinators mostly focus on new arrivals, and not on pupils at the higher end of the proficiency scale, children with higher abilities may be recorded with less accuracy.

Choudry also believes the proficiency levels in the Welsh system are too basic and that pupils should be separately assessed in all areas — speaking, reading, listening and writing — and in different subjects.

A child could have better proficiency of English in maths lessons, but less so in geography. Or a child could understand oral questions, but have limited reading.

Furthermore, she said, the levels miss crucial differences between language expectations at primary versus secondary schools.

In Wales, school funding is based on need. Early stage learners receive higher weightings, and money is issued to cover the cost of EAL teachers, teaching assistants, or training.

See below for a description of the new codes

The DfE has not said the information gathered in England will be used for funding and, although it did say that recording pupils’ country of birth and nationality could be used to “target support”, no additional funding has yet been promised.

Instead, EAL funding — like most school funding — has been slashed in recent years and is no longer ring-fenced. It is now only provided for three years after a child is registered as EAL, but it can take up to seven years for a child to become fluent in English.

However, Smith queried the accuracy of EAL data if funding was attached to the levels, suggesting the DfE would find “rather more new arrivals than [it] previously thought, because people will play the system”.

The accuracy of data collection in Wales has also been questioned in a report by Jonathan Brentnall, an education consultant, who assessed the Welsh system.

Leedham said there had been a “grassroots” movement of sorts to make sure there was a consistent method of assessment of EAL, and that it was wrong to just “grab the [scales] from Wales, without consultation”.

She added: “There is no guidance, we do not know if they are going to be best fit, and there is going to be no moderation. It just doesn’t sit well.”

It is also not clear how the data will be used.

The government has said that it wants to find out how well pupils perform at school, but the department has also asked for a report into the “impact” of “mass migration” on schools. It stresses that the two projects are separate, but there are concerns in light of Brexit and a narrative across the country about the “impact” of immigration, particularly from eastern Europe, on public services.

Leedham said it was important to note there was “no evidence” of negative impact of EAL pupils on schools and other pupils.

“My gut says this data collection doesn’t bode well. Why would you want to measure the impact of the children on the system if your interest was on best outcomes for those children? It doesn’t make sense.”

Jen Persson, from DefendDigitalMe, a campaign group calling for more transparency with pupil data, said: “Where statistics are already available for the legitimate educational purposes of children, we shouldn’t hand over unquestioningly our named individual children’s entire family and educational history to central government for fuzzy purposes.”

Getting the data might also put schools in a difficult position. As Smith asked: “What are you going to do? Ask to see people’s passports?”

Leedham said: “The whole ‘go home’ discourse just makes this even more sensitive.” She said even “white, middle-class families” might be concerned about providing such information.

All commentators said that to be worthwhile, the recording of proficiency levels required a long-term assessment of a child across all subjects, made by someone with the correct training, in a consistent manner across all schools.

A DfE spokesperson said: “The department will collect data on pupils’ country of birth, nationality and level of English proficiency through the school census in line with the national population census.

“The information will be used to help the DfE better understand how children with, for example, English as an additional language, perform in terms of broader learning.”

These were good aims, Smith agreed, but he was unconvinced that it would make for better-informed policy-making.

“If you get poor quality data that you use to formulate policy you are going to get poor quality results.

“I am still struggling to understand what they are going to do with the data. If it is at all accurate, they will find out that proficiency band A, which is pupils very new to English, won’t be doing as well in tests as others. But I can tell them that now.”

The five new codes to assess EAL pupils

The pupil may:

The pupil may:

Use first language for learning and other purposes

Remain completely silent in the classroom

Be copying/repeating some words or phrases

Understand some everyday expressions in English but may have minimal or no literacy in English

Needs a considerable amount of EAL support.

The pupil may:

The pupil may:

Follow day-to-day social communication in English and participate in learning activities with support

Begin to use spoken English for social purposes

Understand simple instructions and can follow narrative/accounts with visual support

Have developed some skills in reading and writing

Have become familiar with some subject specific vocabulary

Still needs a significant amount of EAL support to access curriculum.

The pupil may:

Participate in learning activities with increasing independence

Be able to express self orally in English, but structural inaccuracies are still apparent

Be able to follow abstract concepts and more complex written English

Literacy will require ongoing support, particularly for understanding text and writing.

Requires ongoing EAL support to access curriculum fully.

Oral English developing well, enabling successful engagement in activities across the curriculum

Can read and understand a wide variety of texts

Written English may lack complexity and contain occasional evidence of errors in structure

Needs some support to access subtle nuances of meaning, to refine English usage, and to develop abstract vocabulary

Needs some/occasional EAL support to access complex curriculum material and tasks.

Can operate across the curriculum to a level of competence equivalent to a pupil who uses English as first language.

Operates without EAL support across the curriculum.

Much of what is said about previous practice is simply not true. As an ex EAL co-ordinator and teacher in 4 London schools,I can tell you we assessed EAL pupils carefully at each stage of development, integrating those assessments into the NC assessments. We also made an effort to see to the needs of Advanced Bilingual Learners through supported classroom practice and projects. These systems were constantly questioned and refined. Please remember also that since 2010 funding for EAL was pulled just as we were getting a huge influx from Europe. These codes are just new labels for the same stages we always had. The bureaucrats would do well to be more in touch with what teachers REALLY do!

Couldn’t have said it better myself Paul!

Really interesting article, learned a lot. This bit however:-

“Di Leedham , an EAL specialist, said many schools did not have up-to-date data systems meaning some languages weren’t available to select.”

isn’t correct.

The main MIS systems have a comprehensive list of languages to select from and if a language isn’t in there it can be added by the user.

Simple, if we expect positive outcomes then schools should have integrated

EAL training for whole staff. Allowing staff to be more aware of their EAL students and their early requirements of learning a new language, alongside learning the N.C.