Students arriving in schools without fluent English can thrive, but it depends where they live and how their schools use their pupil premium pot. Look at the statistics and you’ll see how the achievement “gap” varies hugely at different ages and in different areas. London pupils do best of all . . . as an EAL specialist, says, the capital city “been dealing with it for a lot longer”

One in six school children is classed as learning English as an additional language (EAL), double the proportion of 1997.

It means that more than 1.1 million children now enter school with a need for extra language support, on top of any other needs that they may have.

But teaching practices for these children seem to be a postcode lottery.

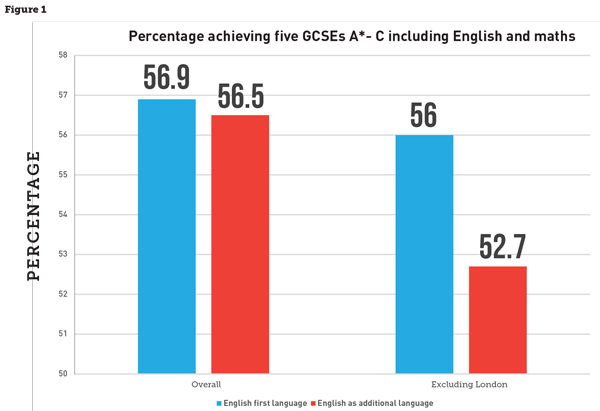

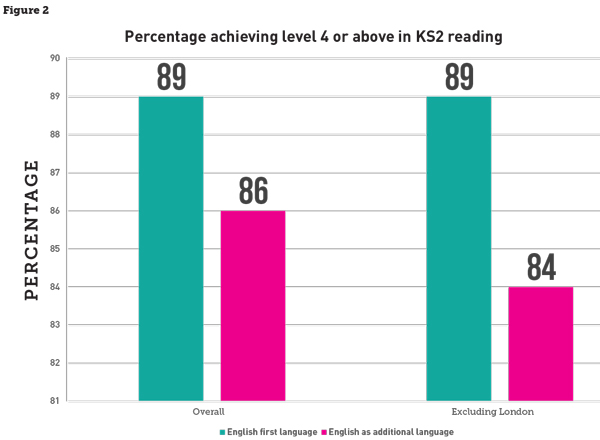

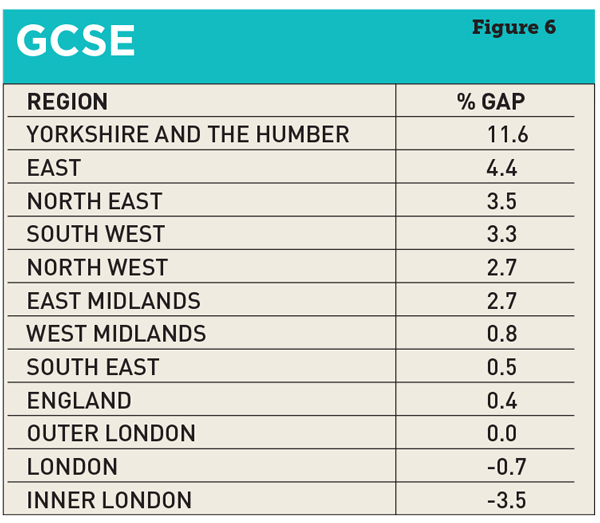

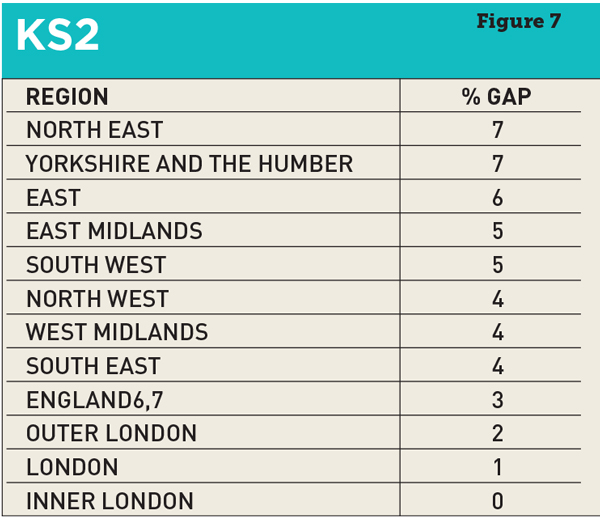

Looking at the national “gap” between EAL learners and their peers, there is just a 0.4 percentage point difference in achievement at key stage 4 [Fig 1], and three percentage points at key stage 2 [Fig 2].

But this includes figures for London, which has benefited from years of extra support in the early 2000s and is arguably ahead of most areas at meeting the needs of pupils from other countries. The city is a multicultural hub, whereas a small primary in a Yorkshire village may struggle when suddenly faced with the need to teach EAL pupils.

Taking London out of the equation, the achievement gap between EAL learners and first-language English speakers widens by 3.3 percentage points for GCSEs [Fig 1] and five percentage points in key stage 2 SATs [Fig 2].

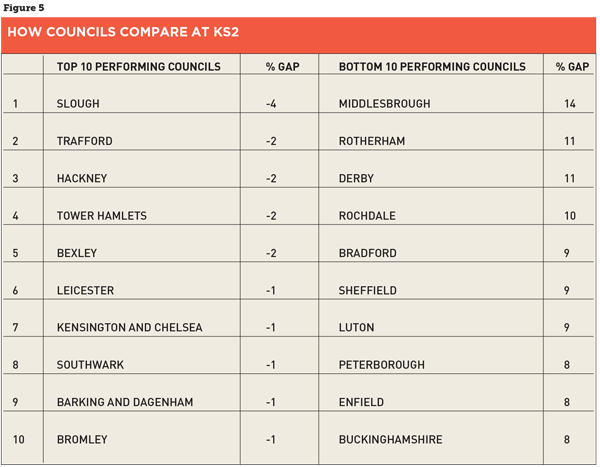

Between the best and worst performing councils for EAL learners, there is a staggering 45 percentage points’ difference for GCSE outcomes, although there is no evidence that an EAL pupil impacts the learning of his or her classmates.

Graham Smith, managing director of EAL Academy, which trains teachers in dealing with multi-lingual learners, says there are “major” problems outside London.

“London has just been dealing with it for a lot longer. And the London Challenge made a huge difference; it took the local authorities with really good people and made them available across London. That was a step-change.

“In some places, just five years ago, it was unthinkable for schools to have to think about EAL. But there has been a demographic change and many areas do not have the provision, especially coastal towns. The cuts in local authorities have led to a loss of local expertise.”

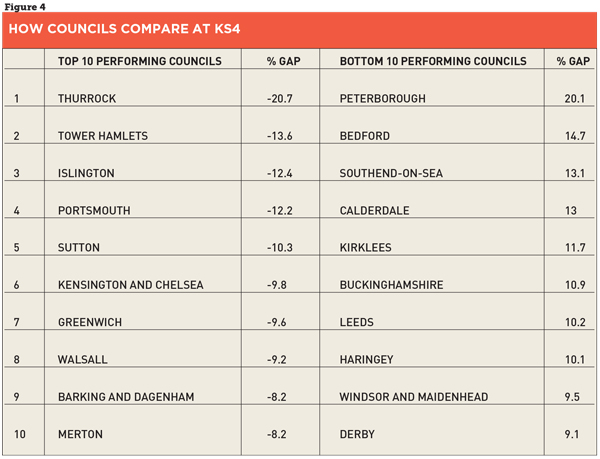

At key stage 4, EAL learners in Peterborough are behind their peers by 20 percentage points – the worst in the country [Fig 4]. Of the ten councils where EAL learners are ahead of English as a first language speakers, seven are in London.

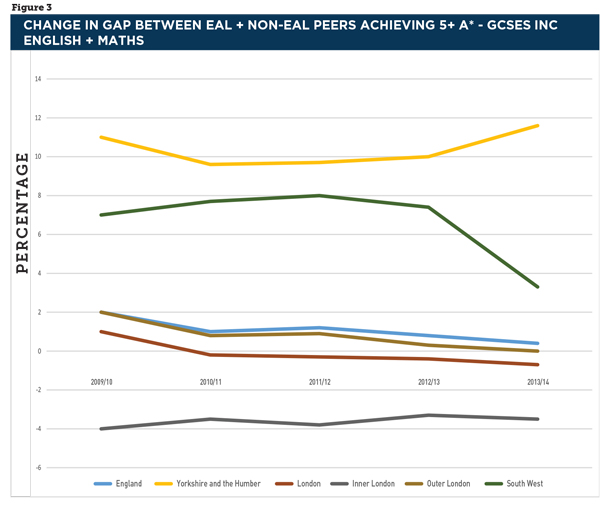

Nationally, the achievement gap is falling – slowly and minutely, with London leading the overall pattern. But there are some anomalies [Fig 3].

For two years, schools in Yorkshire and the Humber managed to narrow the gap slightly, but last summer it widened again. Meanwhile, in the South West, after four years of meandering around the same difference in outcomes, the gap suddenly narrowed, falling a further three percentage points.

Mr Smith believes initial teacher training (ITT) could help to build up expertise in schools. Although he worries that fewer would-be teacher are now being recruited.

“Government just doesn’t have any idea what is going on. The expertise has been lost. An excellent history or geography teacher can be an excellent EAL teacher, but that isn’t happening. EAL may just be one small part during ITT; there needs to be more focus. Too many EAL pupils are being supported by teaching assistants and that is not the best way for them to learn.”

Funding plays a key part; money for EAL learners is only available for the first three years of a child entering the English school system.

But as Diane Leedham of NALDIC, an organisation that promotes the effective teaching and learning of English as an additional language, explains: “It takes up to five to seven years to have complete fluency in a language. The advanced learners look like they are speaking really well but they do still need adaptive teaching and there is no funding for that.”

The pupil premium is available for disadvantaged children. But the only dedicated grant to help EAL learners was scrapped by the coalition government in 2011.

The Ethnic Minority Achievement Grant (EMAG) was merged into schools’ overall budget, the Dedicated Schools Grant; it is therefore no longer ring-fenced and schools and councils must fund support for EAL learners from a shallower pool.

A Department for Education spokesperson said: “Many schools teach pupils whose first language is not English successfully and we have protected school funding since 2010 to ensure they have the resources they need to meet the individual needs of all their pupils.

“We have also given them the freedom to use that funding as they see fit. Through the school funding formula, councils can and do provide more support for pupils with English as an additional language. It is for councils to decide themselves how much money they allocate.”

Schools can also use their pupil premium, although being an EAL learner does not mean you are entitled to that funding.

Yet, according to a report by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), 22 local authorities did not include an EAL factor when delegating money to schools.

Frank Monaghan, NALDIC deputy chair and a senior lecturer at the Open University, said: “Local authorities used to be held accountable for how they used the EMAG.

“What they receive now is less than a premiership football club pays in wages a week. In the grand scheme of things it is a very small amount of money, but we just have no idea where it is going.”

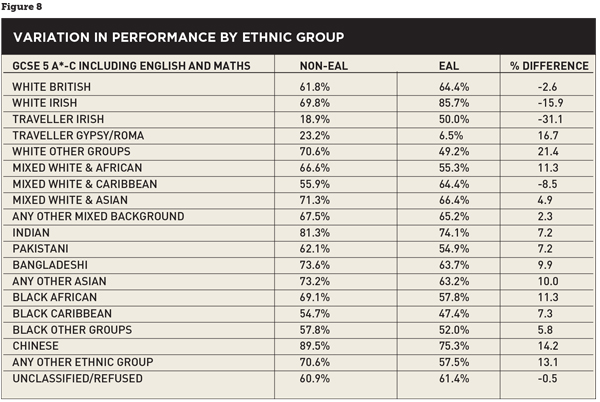

Although understanding the number of children from each background is complex, as Ms Leedham explains: “Some parents do not want to identify themselves as Roma, for example, and that complicates matters.

“But then if you dig down into ethnicity and EAL there are some very big differences in performance.”

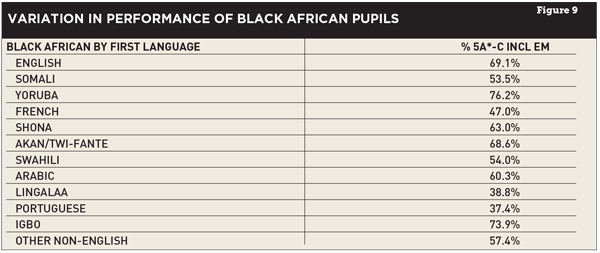

Take black African children for example, a group that covers a huge number of languages and cultures [Fig 9]. They are 11.3 percentage points behind their non-EAL peers [Fig 8]. Yet, if you look at those children by their “first language”, including English, their performance at GCSE ranges from 37.4 per cent for those with Portuguese as their mother tongue up to 76.2 per cent for Yoruba-speaking children (predominately those from Nigeria).

Teaching children with EAL is complex, and an issue that is likely to become more important. But as Mr Smith argues: “To teach EAL, you will be an excellent teacher to begin with and that can only benefit the other pupils in the classroom, and help other staff in the school.”

Your thoughts