Grammar schools and free schools may be exacerbating social segregation, new research released today shows.

Analysis of the deprivation levels at primary and secondary schools in England compared with deprivation in their local area, by education data company School Dash, has found that poorer pupils are hugely underrepresented at particular types of schools.

School Dash founder Timo Hannay (pictured above) has blogged about the findings in full, and Schools Week has pulled out the key findings below.

More affluent families live closer to good schools

Perhaps not the most surprising finding, and well known to anyone attempting to get their child a place at the “best” local school, based on Ofsted ratings.

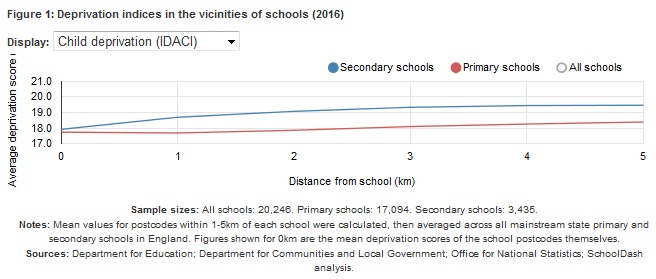

Hannay has used the Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI) to measure deprivation of an area. The higher the IDACI percentage, the more deprived the population.

At secondary school, families with 19.3-19.5 per cent IDACI are more likely to live between three and five kilometres from a school. Those that live within a kilometre of a secondary school are at 17.9 per cent on the IDACI scale.

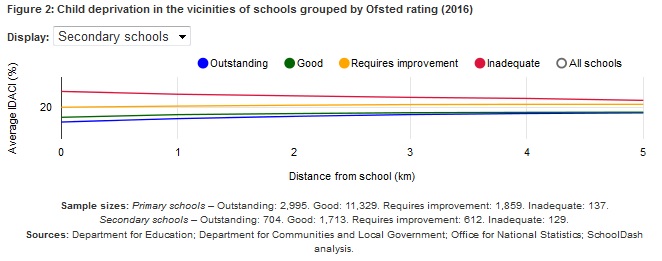

But, when taken in tandem with Ofsted ratings, the IDACI per cent falls even more (i.e. the area gets richer) so that those living within one kilometre of an outstanding secondary have an IDACI score of 15.5 per cent, and those living within one kilometre of an inadequate school have an IDACI score of 25.3 per cent.

In other words, poorer pupils live closer to failing schools.

This picture is similar at primary school, although less pronounced: within one kilometre of outstanding primaries there is an IDACI score of 14.6 per cent, and 22.4 per cent for inadequate primary schools.

Primary free schools are “biased” against poor pupils

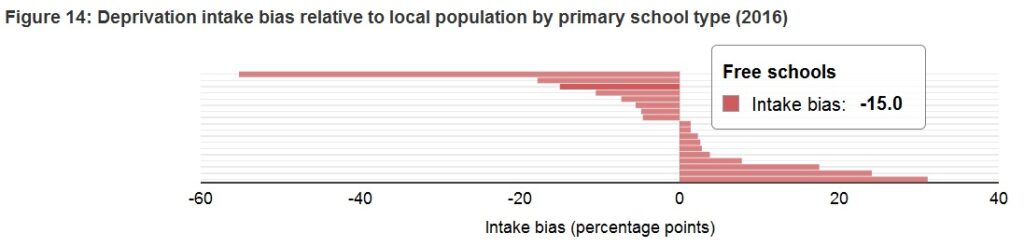

Using an indicator for how many pupils in a school are in receipt of free school meals compared with the total amount eligible in a school’s area, Hannay has broken down how “biased” schools are against the typical population and their intake.

There is large variation of bias across all the types of schools analysed. But primary free schools stand out as one of the most biased against the poorer children in their locality.

Essentially, they have a lower proportion of disadvantaged pupils than their local communities – or to be precise, a -15 percentage points bias, as shown in the graph below. (Not quite the message Michael Gove had when he launched the free schools programme five years ago).

This level of bias is only topped by outstanding primaries (-17.8 percentage points), and faith schools (non Christian) with -55.2 percentage points.

Speaking to the Guardian, free school advocate and founder Toby Young backed calls for a universal admissions policy to tackle this problem.

Inadequate, requires improvement, sponsor-led and non-faith schools have the greatest proportion of FSM pupils compared with the local area: i.e. these schools taken in more FSM pupils than the area’s average.

Interestingly, the picture is different for secondary free schools, where there is a positive bias towards poorer pupils (6.1 percentage points).

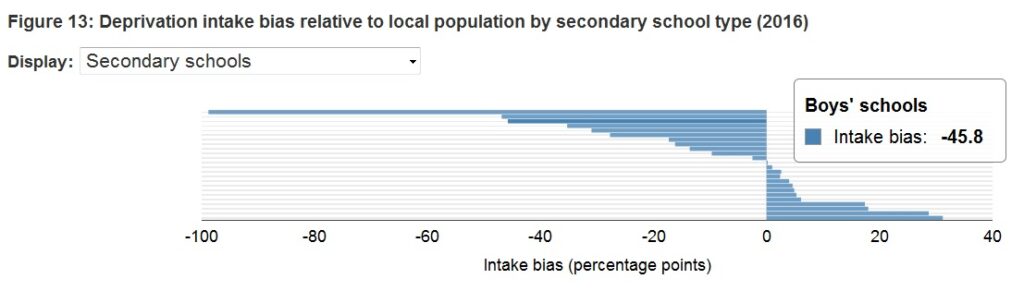

Grammar and single-sex schools are the most biased towards affluent pupils

The same analysis for secondary schools shows grammar schools, academically selective at age 11, are by far the most biased towards more affluent pupils (-98.8 percentage points) – suggesting they aren’t quite the “engines of social mobility” some grammar school advocates say they are.

With the grammar school debate heating up again, proponents, such as prime minister Theresa May, might perhaps want to consider the implication of a potential expansion of the programme on the most disadvantaged children.

Single sex schools are also very high up in bias towards richer pupils, with boys’ schools being the most (-45.8 percentage points, pictured below) and girls’ at -27.7 percentage points. Faith schools (non-Christian), as with primary schools, are also biased towards the more affluent.

As with primaries, the lowest performing schools Ofsted-wise are also the most likely to have more poor pupils than their local community’s make-up would reflect.

The OECD warned in 2011 that the free schools and academies programme would need careful monitoring to ensure it did not increase social segregation. In 2015, the OECD found that there was no correlation between increasing school ‘choice’ and improved results BUT found that school choice increased social segregation.

Yet this Government is committed to the policy of school ‘choice’ arguing that choice will increase school performance. It doesn’t.