The national funding formula sits in the wings while the government attempts to sort Brexit. But is it worth waiting for?

When he was asked about schools closing early on Fridays as a result of squeezed funding, Philip Hammond suggested skewed funding was “giving rise to the unhappiness and disquiet”.

The chancellor, speaking on The Andrew Marr Show on Sunday, said the government’s new national funding formula (NFF) would sort this out, ensuring money was “spread more fairly”. But it would “take time”.

So where are we up to with the NFF?

A Schools Week investigation shows that the results are mixed.

First, funding experts have dismissed the chancellor’s claims that the NFF is the solution to the cash crisis in schools.

Second, the government’s fixation with Brexit may delay the roll-out of the full NFF – which will mean cash-strapped schools facing a longer wait for their full allocation of money.

And third, after spending years working towards delivering a fair funding system that is more transparent and equitable – and fighting huge political opposition – it appears the government’s academy reforms have opened a loophole that shoot down those principles.

Where are we at?

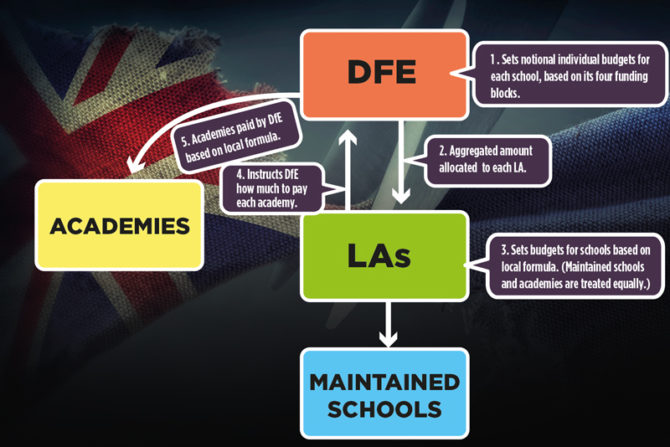

Schools are operating on a “soft” NFF, which means the government works out “notional” individual budgets, based on its national funding formula blocks.

These are: a basic per-pupil funding allocation, additional needs funding, school-led funding (includes PFI contracts, rates and other exceptional circumstances) and an area cost adjustment.

Schools aren’t guaranteed to get their full gains

This is then totted up to give the total school block budget for each local authority (covering maintained schools and academies). Councils then set their own local formula – in agreement with school forums made up of headteachers – to distribute the cash.

Under the hard formula, the funding would go directly from government to schools, cutting out councils.

But Julia Harnden, a funding specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders, said: “There are unintended consequences of the soft formula. While there is flexibility for local authorities, schools aren’t guaranteed to get their full gains.”

Ministers introduced transition arrangements for a “soft” funding formula until 2019-20, basically because the hard formula needs legislation – and that’s tricky with Brexit running the show.

Those arrangements have been extended for another year, meaning the hard formula won’t be introduced until at least September 2021.

Spending review uncertainty means schools could miss out for longer

The government launched a NFF consultation in 2016. The original plans to redistribute cash meant that 9,045 schools would lose funding so that 10,653 could get more.

This was soon abandoned. In 2017, Justine Greening, then education secretary, found £1.3 billion to ensure all schools would be guaranteed, on average, a 0.5 per cent per-pupil cash increase until 2020.

It won’t solve the shortage in funding

But the schools set to benefit (those that had been under-funded) also had their gains capped at 3 per cent a year (for 2018-19 and 2019-20).

From 2020 onwards, however, it will all hinge on the spending review.

“There’s still uncertainty,” Harnden said. “We don’t have any reassurance that any growth will be continued. Those reassurances are really necessary.”

The Department for Education pointed us to comments made by Damian Hinds, the education secretary, this weekend that he will “back headteachers to have the resources they need to deliver a world-class education”.

Brexit could torpedo full fair funding roll-out

But will that be enough?

Hammond has hinted at upping public sector spending if a Brexit deal is agreed. But that seems a big if. And there are worries that Brexit will kick the full roll-out into the long grass.

Jonathan Simons, the director of education and social policy at Public First, said: “Given not just the lack of parliamentary time, but the lack of a majority for almost anything vaguely controversial the government wants to do, it seems unlikely that the necessary legislative time will be found until Brexit is resolved one way or the other – which would be years not months.”

A long-term soft formula is problematic for a few reasons.

Just 41 of the country’s 152 councils are using funding settlements that “mirror the NFF factor values almost exactly”, while another 73 have moved their funding plans “closer” to what is proposed. That leaves schools in 38 council areas potentially not funded fairly.

Councils don’t have to, for instance, include the NFF’s minimum per-pupil levels in their own local funding formulas. They can also transfer 0.5 per cent of the funding to other areas, such as high needs. While this can only be done in agreement with the schools forum, it’s still a thorn in the pledge for funding fairness.

Schools Week has also been told that the role of local authorities in the hard funding formula is still to be ironed out. That local input is important on particular issues, for instance schools with private finance initiatives (repayment of contracts varies wildly across the country, so a one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t work too well).

MAT system wipes out benefits of national funding formula

There’s also growing unease in some quarters over how academy freedoms conflict with the hard-fought principles underpinning the national funding formula: transparency and fairness.

An increasing number of academy trusts are choosing to pool the general annual grant (GAG) allocated to their schools. This allows them to set the budgets for their academies, based on any formula they determine.

Large trusts that pool their GAGs include Inspiration Trust and E-ACT.

While the funding method has huge positives – it allows trusts to smooth out deficits in some of their schools by using surpluses from others – it’s controversial.

For instance, how funding is divvied up is decided by academy bosses behind closed doors.

Natalie Perera, the head of research at the Education Policy Institute (EPI), says: “The DfE has radically reformed funding arrangements between local authorities and schools to improve transparency and consistency.

“But now that most secondaries are in MATs, where there are no rules about how funding is top-sliced or allocated to individual academies, there is a real risk that we lose that transparency.

“Transparency and equity are core principles [of the NFF]. That means a similar pupil in a similar school will attract similar levels of funding. This jeopardises that.”

The DfE said that trusts must “give consideration of the funding needs for each individual academy, to provide the correct support for the children at each academy”.

Academies can also complain to their trust about their funding levels. If they don’t feel this has been resolved, the secretary of state will make a final decision – and can overrule the trust.

So will the NFF solve the cash crisis?

As Schools Week has previously reported, there is wiggle room in the system. An analysis by the EPI found that four-fifths of local authorities could wipe out their maintained schools’ deficits by clawing back the “excess” surplus posted by their cash-rich schools.

The total value of schools banking what the government deems as an “excess” surplus last year was nearly £600 million – enough to wipe out the £233 million deficits throughout the country nearly three times over.

But schools have good reason to hold on to extra cash: capital funding is less forthcoming and times are uncertain.

Local authority and school expenditure statistics for 2017-18 show that 30 schools posted uncommitted revenue balances of more than £1 million. One school, George Green’s in east London, posted £2 million.

Five of the top ten cash-rich schools are in Tower Hamlets, east London, with another two in Slough, and one each in Newham, east London, Southwark, south London, and Reading.

All of these areas were due to lose money under the original funding formula, suggesting the government has identified the right areas as over-funded.

At the other end of the spectrum, 69 council schools posted deficits of more than £500,000 last year.

However, none of the councils with schools with the highest deficits were due for the largest increases under year one of the NFF.

So is the national funding formula the answer?

The consensus seems to be that it will help, but isn’t a silver bullet.

Harnden said: “It won’t solve the shortage in funding. We’ve got to be clear on that.”

Perera added that the formula would redistribute money in a transparent way, but whether it was enough money was “an entirely different question”.

The DfE said the national funding formula was an “historic reform that is directing money where it is most needed, based on schools’ and pupils’ needs and characteristics – not accidents of geography or history”.

Since 2017, it added, it had given every council more money for every pupil. “Ensuring stability” for all schools was a “consistent message when consulting the sector”.

The current arrangements “strike the right balance”, it added. Further decisions would be part of the upcoming spending review.

Your thoughts