The Department for Education (DfE) has today released this year’s performance tables for primary schools, based on this summer’s SATs results.

The government said schools were “rising to the challenges” after it brought in a raft of changes in key stage 2 (KS2) tests – such as introducing higher floor standards, banning calculators for maths tests and introducing a spelling, punctuation and grammar test.

The DfE said this year 676 schools failed to meet its floor standards compared to 768 in 2014, when the floor standard was increased.

A school is below the floor standard if fewer than 65 per cent of pupils achieve at least a level 4 in reading, writing and maths, and it has below the national average percentage for pupils making expected progress in each subject.

Nationally, 80 per cent of pupils achieved the a level 4 in all three subjects. This is a slight increase from last year, when 79 per cent did so.

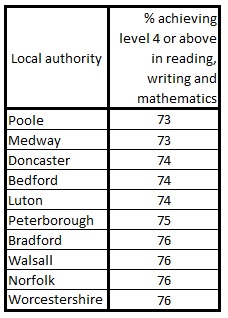

The DfE highlighted the 10 local authorities with the lowest performance.

Half of the 10 are in the south of England (pictured below). This contrasts with Ofsted’s revelation last week showing that the majority of under-performing secondary schools were in the north and Midlands.

Poole, the joint lowest-performing authority in today’s primary results, was congratulated by Schools Week earlier int the year for being the authority with the second most increased GCSE results in the country – showing how primary and secondary schools in the same area can vary widely in their performance.

Poole, the joint lowest-performing authority in today’s primary results, was congratulated by Schools Week earlier int the year for being the authority with the second most increased GCSE results in the country – showing how primary and secondary schools in the same area can vary widely in their performance.

Schools minister Nick Gibb will have met with 13 local authorities where KS2 results are “disappointingly low” by the end of the year, the DfE statement said.

After the provisional results were published in the summer Mr Gibb wrote to the worst local authorities to “demand an explanation” and ask what was being done to raise standards.

Mr Gibb said: “It is essential that every child leaves primary school having mastered the basics in reading, writing and maths – thanks to our education reforms thousands more pupils each year are reaching those standards.

“The increased performance at primary level across the country demonstrates how this government is delivering on its commitment to provide educational excellence everywhere and ensure every child benefits from the best possible start in life, no matter where they come from.”

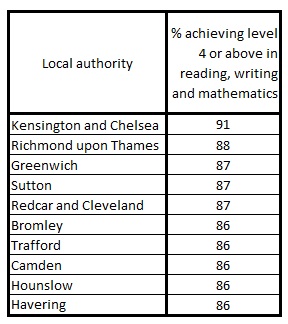

The top performing local authorities (pictured left) were also highlighted by the department. The majority are London boroughs, but two northern local authorities also made the table.

The top performing local authorities (pictured left) were also highlighted by the department. The majority are London boroughs, but two northern local authorities also made the table.

The DfE said Rutland, in the East Midlands, and Devon are also in the top 10 areas for the number of primaries where all pupils score 100 per cent in the reading, writing and maths.

See Schools Week’s ‘Golden 28’ league table which celebrates the 28 schools in which disadvantaged pupils achieved the best outcomes.

Gibb is judging the LAs at the bottom of the league table on results alone. In Bradford, for example, 104 primary schools are Good or better, 56 Require Improvement and just one is Inadequate. Similarly in Peterborough, 52 primary schools are Good or better, 5 Require Improvement and just one is Inadequate.

If LAs like these are judged solely on results, then can we expect all the areas’ primary schools to be forced to become academies despite the majority being Good or better? This would be unacceptable.

If LAs are ranked according to their averages, there will always be some at the bottom end. Gibb describes these results as ‘disappointingly low’ and the LAs, therefore, can expect a personal visit during which he will demand explanations.

But his intervention could be precipitous. Three of the bottom ten – Bedford, Luton and Worcestershire – have not yet had their schools improvement services inspected by Ofsted. This should be done before Gibb blunders in.

Of the remaining seven, the schools improvement services of two (Peterborough and Norfolk) were judged ‘effective’. The remaining five schools improvement services were criticised but there were chinks on light in four of them. In Poole (July 2015), for example, school leaders said school improvement was slowly becoming more effective. In Doncaster (March 2015), the LA was addressing previously noted areas of improvement with ‘vigour and urgency’. In Walsall (April 2016), inspectors found improvements since the last (Inadequate) inspection although there was still a ‘great deal to be done’. In Bradford, there was ’cause for optimism’.

Any heavy-handed intervention by Nick Gibb could trample these seedlings of recovery.