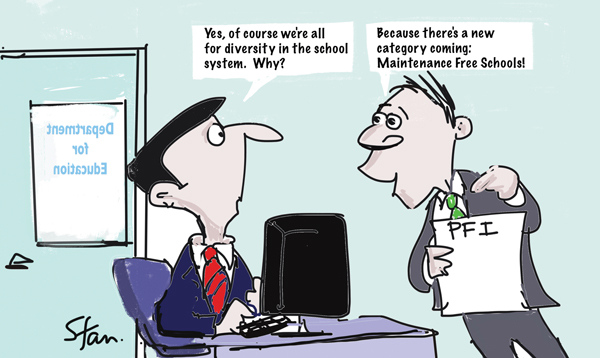

Cash-strapped schools are being pushed into financial ruin by soaring debts owed to the private firms that funded their buildings, Schools Week can exclusively reveal.

Takeovers of underperforming schools have also stalled due to the hefty costs associated with the contracts.

Annual repayments in some schools with private finance initiative (PFI) contracts have soared by £125,000, forcing staffing cuts to balance their books. In others, costs are escalating at a rate of around £30,000 each year – the salary of an average teacher.

Schools in Stoke-on-Trent are locked into 25-year contracts to pay off a consortium of private companies who funded new buildings and refurbishments in 2000 as part of a £153 million deal with Stoke council.

One of the schools, Birches Head Academy (pictured above), is paying more than £380,000 a year on PFI costs – up by more than £125,000 in just four years.

Roisin Maguire, the academy’s consultant headteacher, said: “When schools are having to make people redundant to pay huge PFI contracts, then something is wrong.”

She described the contract as “unsustainable” as the costs were based on the school being funded for a full quota of pupils. At present only 60 per cent of places are filled at the school.

St Joseph’s College, where Ms Maguire is headteacher, is considering sponsoring Birches Head to get it back on track but she said the governors “don’t want to take on a financial liability”.

Elsewhere in the city, Ormiston Academies Trust (OAT) is the preferred sponsor to take over two schools said to be struggling financially, Sandon College and Packmoor Primary.

But the takeover has been delayed as the trust investigates the PFI costs lumped with the schools. The yearly rise in PFI costs at Sandon – which is in special measures – is believed to be the equivalent of funding one maths teacher.

A large chunk of the cost increase faced by the school is to make up for an estimated shortfall in funds after it was reported the council could run out of money to pay for the contract – six years before the deal was due to ends.

Professor Toby Salt, OAT chief executive, has written to schools minister Lord Nash this week to raise his concerns.

But the problem isn’t confined to Stoke.

Using public records, Schools Week uncovered 128 academies paying almost £70 million in the 2013-14 financial year on PFI costs, which is an average of more than £500,000 per school.

The figures suggest the cost of contracts at some schools rocketed by nearly £200,000 in just 12 months – the equivalent of three senior leaders’ wages.

Total amounts paid to private firms under the deals will be even higher as costs for local authority schools are not centrally available and were not included in the analysis.

In Stoke’s case, the PFI scheme was set up by the local authority and private firm Balfour Beatty. It is now run by a dedicated PFI company called Transform Schools.

The Financial Times reported that Balfour sold its stake in four school PFI projects – including Stoke – to infrastructure investment company Innisfree in 2013. The paper said that Balfour made a gain of nearly £24.4 million on its equity in the projects.

Ms Maguire said the PFI repayments were forcing Stoke schools to cut costs: “Something is going to have to give. It’s coming to a head.”

Two school leaders we spoke to described the PFI contracts as “toxic”. Another couldn’t publicly speak about his school’s contract because he said it had a gagging clause.

One academy chain head, with PFI contracts averaging £400,000 across its schools, said: “It’s a bit like every time you want to drive somewhere you have to take a taxi with the meter running – that’s the reality.”

According to annual accounts, the Cabot Learning Federation paid £888,000 in PFI facilities management costs alone last year for two schools.

One of its schools, Bristol Brunel Academy – built under the Building Schools for the Future programme in 2007 – paid £561,000 for maintenance in 2013/14.

Steve Taylor, chief executive of Cabot, told Schools Week the state-of-the-art school provided real advantages for pupils.

But if the current above-inflation contract increases continued, it would be “considerably less affordable”.

Antony Power, a partner and head of education at law firm Michelmores, said academies faced being driven into deficits unless they took greater control of their PFI costs.

“Unless things change, the problems are likely to get worse as time goes on. At the moment inflation is low; when it rises, the PFI costs will rise more steeply, probably faster than school budgets.”

Stoke council said it was in talks with Birches Head to review its costs. A spokesperson also said it had met with Ormiston officials to warn that converting did not relieve schools from the contract. If they did, it would place “huge financial burdens on the remaining schools in the PFI contract and the council”.

How PFI works

Private finance initiatives involve the private sector financing, building and operating public infrastructure, such as schools.

The private firms are repaid through leases spanning 25 or 30 years which, in the case of schools, are signed by local authorities.

It was used to build and repair secondary schools under the Building Schools for the Future (BSF) programme, which nearly 100 local authorities had signed up to by 2009.

The scheme was the brainchild of the Conservatives, but later became popular under the Labour government towards the end of the 1990s as its “buy now, pay later” structure provided new infrastructure without needing money up front.

But problems emerged over the price of repaying the contracts – which, in some cases, have spiralled to seven times the original investment.

An investigation by the Independent on Sunday newspaper this year found the UK owes more than £222 billion from PFI deals – more than £3,400 per person. It rose by £5 billion last year alone.

Schools Week found many schools are now facing financial problems as they cut costs to meet squeezed budgets.

Local authorities mostly pay for the PFI buildings contract but schools are locked into facilities management repayments, which can include cleaning, caretaking and catering, over the contract span and which come directly from their own budgets.

For instance, in two Bristol schools taken over by the Cabot Learning Federation, the local authority continues to pay the costs of the building, part of Bristol’s Building Schools for the Future programme.

However, the trust has taken on the facilities management contract for the academies. It has agreed to repay a percentage of the overall facilities bill based on the funding that would have been available to the local authority if it had stayed a maintained school.

Former education secretary Michael Gove scrapped the BSF scheme in 2010 because of “massive overspends”.

The government’s new building programme will deliver 46 schools under a new scheme called PF2. Chancellor George Osborne has said this will be more transparent and better value for money.

I don’t know if the PFI contracts in Worcs are typical of those in other LAs “blessed” with shiny new Privately maintained schools, but the many pupils in Worcs pay a subsidy from their education funds to sustain the private schools of the few. There is a PFI factor in the funding formula so I’m guessing that this bizarre notion of the many paying for the few is considered “reasonable”, “best practice” even, despite that it goes against all the principles of the drive for fairer funding.

The Government of the time agreed to pay most of the capital development costs and this was typically spread across the life of the project with interest calculated at the start and amortised into fixed annual payments. One of the big 5 consultancy firms probably received a 7-figure sum just to set it up. The government weren’t willing to pay all of the capital costs so the LAs were “invited” to use some of “their” money (actually the children’s ringfenced education funds) to pay an annual capital subsidy (but at least it’s a fixed cost).

However, the story doesn’t end there. Schools don’t own the buildings so they pay a management fee to the PFI owner. At a time of fixed cash per pupil – now running for more than 5 years – these fees are indexed linked, possibly inflation plus (because finance has to make a profit, right?). The private companies carry no risk whatsoever. PFI is that rare thing in life – a sure thing. But even that only partly explains the affordability gap PFI schools are facing.

In Worcs, in 2005 when our scheme was “dreamt up” (although it feels more like a nightmare now), boom and bust had been eradicated, “Education, education, education” was the theme of the day, the sun never set on New Labour’s bright ideas to spend more and more money to save us all. In the arrogance and hubris of the times several of the largest PFI schools were built 29% to 40% bigger than the schools they replaced. Not only have we paid the capital costs for a big building, the management fees we pay are based on a full school.

We all know that school funding is pupil based so every pupil of spare capacity adds to the per pupil costs of the rest. We never came close to filling that spare capacity in Worcs. The County admissions policy actually restricts growth in some cases and some schools have actually seen numbers reduced. This isn’t a “new, exclusive” story. This is a tragic scandal that has been going on under our noses for years, covered up by a lack of transparency in the name of commercial sensitivity. Teaching & Learning in PFI schools has been under strain and probably compromised from the outset. It’s coming to light now, less than a third of the way through some contracts, as the final nails are put into the coffins of the schools.

One final twist, Worcs is one of the least fairly funded LAs in the country. Last year we received £6.2M top-up based on our funding of 8 or so key formula factors. A minimum funding level was determined for these key factors and if those factors applied to our pupil data generated a number greater than our schools block funding, then we got a top-up. PFI is in our schools block, but it isn’t one of the key factors. Our top-up would have been £2.5M bigger if PFI wasn’t dragging us down. Fortunately, the top-up has been agreed for this year too, so that’s only another £2.5M we lose to PFI. A couple of million here, a couple of million there; pretty soon you’re talking serious money.

Labour sold off many of our schools and moved the pupils into new, rented accommodation. They did with hospitals too. The landlords have no interest in education or health. Their only interest is making profit from their facilities. It’s not even their fault that the management fees are based on full capacity. They were asked to build larger faciltities; they kept their side of the bargain (but why wouldn’t they with a guaranteed return?). At least as owner occupiers we could making savings from spare capacity. We could rent out space in the short term or at least share our facilities with our community. Whilst some community access is built into all PFI contracts, there is no incentive for the landlords to maximise it. When PFI doesn’t work, we are powerless to do anything about it except cutback education.

Money is cheap at the moment. We lavished billions on an unworthy banking system. It’s past time we re-nationalised Labour’s private schools and hospitals. We should learn the hard lesson that in precious areas like health and education we should never again mortgage ourselves to disinterested parties. George’s PF2 initiative should be fully publically funded – print a bit more money Geroge for some really worthwhile investments and tell the profiteers to take a hike.

Good article, and nice to see it recognized that PFI does include long term upkeep as well. But they were bad value, no doubt about that.

Despite the big numbers, these would be pretty easily manageable if they were paid by central government, and not loaded onto to LAs and individual schools. In terms of a crisis, it’s as much one of cost allocation as overall cash.

Added to the fact that they are invariably badly designed and built, it adds insult to injury. See this article where BSF is blasted as a wasted opportunity. http://www.bdonline.co.uk/bsf-blasted-as-a-‘wasted-opportunity’/3128633.article Building Slums for the Future more like. A TA I met said, yes, they consulted us, then they just went ahead and did what they wanted. The list is just too long of leaking roofs, too small carparks with too small parking spaces, music rooms not even on the ground floor, let alone having a loading bay for all those outside community gigs. . . .

Oh that Cassandra feeling!

https://www.tes.com/article.aspx?storycode=2108427

I was relieved to leave the secondary schools sector when I did, at the height of BSF. Working in school IT, it was a depressing and bleak time for my peers across the country and it was by far the biggest topic of conversation for month after month as, LA by LA and school by school, IT teams were being taken over by large private firms in partnership with the winning BSF bidders. Invariably and inevitably, schools were getting significantly poorer service at drastically higher costs. We were well aware of the IT staff involved being monitored and in some cases fired for speaking out about their new employers.

You might wonder why the schools chose to hand over their IT support to the private companies rather than sticking with the good-quality support they already had. In many cases they had no choice – they were faced with crumbling buildings, a once in a generation offer of capital investment and an unfortunate all-or-nothing bundling of capital and service elements. Many staff who were TUPEd off or forced out had sympathy for the unenviable decisions their schools’ leadership teams had to make.

At a neighbouring school a politician visited the Head with a very clear threat – the Head would be pushed out of his job if he refused to accept the BSF deal and retained his IT staff: other schools in the LA needed that money and losing a large school (1700ish) would put the whole project at risk. To his credit he had the tenacity to call them on their BS and the school stayed free of it. My school also resisted as it had a good deal of financial independence and could see the perils of being under the control of a for-profit corporation.

Nationally the picture was much worse, and the same atrocious IT services companies which schools had just started to break free from were winning contracts left and right, so schools were back to paying private shareholders £1000 plus materials every time a 22 year old “consultant” from the managed service provider came to resolve a minor technical problem.

If one issue made me vow to never vote for New Labour, it was this one. Gordon Brown was fully responsible for this outrageous attack on the public finances, regardless of who originally dreamed it up, and it was sustained for so long due to a vile mix of vanity, arrogance and pride. A sustainable, steady and long-sighted rebuilding plan would have seen more schools built by 2020 to a higher standard and at a drastically lower cost.

This should have been foreseeable and those signing the BSF contracts and TUPE should be allowed to respond.