Superheads may lift results when they take over failing schools, but what happens when they leave? Laura McInerney reports

“Superheads” recruited to quickly turn around failing schools boost results in the short term but leave schools with plummeting scores and financial black holes when they leave a few years later, a new study shows.

Researchers at the Centre for High Performance observed 160 academies over five years, with unprecedented access to school information systems, enabling them to record pupil, teacher, management and financial performance.

Twenty-one of the schools were identified as having superheads – leaders appointed specifically for quick fixes to exam results and who immediately changed the school’s focus.

They were paid a minimum of £70,000 in primaries and £100,000 in secondaries.

But Schools Week can exclusively reveal the costs went much further.

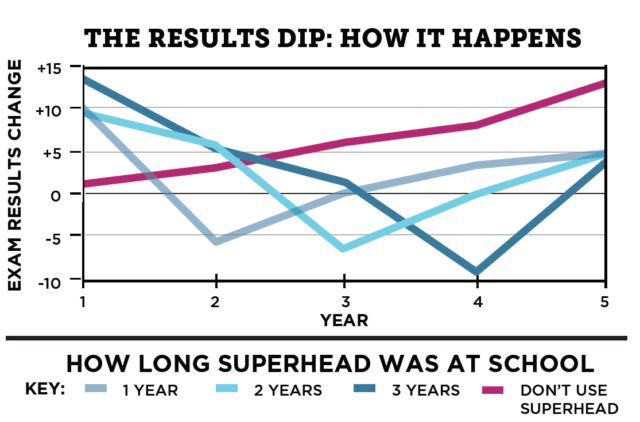

Although results increased during their tenure, scores fell by an average of 6 per cent when they left. And the impact was worse if the head was in place for longer periods, with results dipping 9 per cent if he or she left after three or more years at the school.

The bill for consultants to save the school after results crashed cost £11.8 million across the 21 schools, with three paying more than £1 million each.

“Adding this cost to a superhead salary,” Ben Laker, one of the researchers said, “and it becomes a very expensive mistake.”

By contrast, leaders in the sample who were not superheads saw results climb steadily over the five years.

Co-researcher Alex Hill wants the school sector to realise the long-term damage a focus on quick-win exam results causes.

Hill said: “Because we have access to the management information, we can go to the data and see what has been done. We can see how a whole school works.

“As academies have experimented, some practices have emerged, and there are reasons why they have emerged, but there is little sharing of this knowledge. And some practices emerging are quite questionable.”

Every superhead the pair studied focused on raising maths and English results by narrowing the range of available subjects – for example, integrating drama and dance within English and PE.

Twenty of the 21 super heads also moved “outstanding” teachers to year 11. “It shows up in the management information data,” Hill said. Timetables were restricted to ensure students nearing a C grade received teaching from the best teachers. Doing so meant other year groups did not receive the best teaching, affecting the sustainability of improvement.

The researchers also found that 18 of the 21 removed low-ability pupils from exams if they couldn’t persuade parents to educate them from home, a finding widely reported after the pair addressed a conference in Dubai. Academy advocates vigorously denied this happened.

The lack of data on home-schooled children in England makes it difficult to keep track, but recent evidence from statistics experts at Education DataLab suggests some academies have higher-than-expected pupil turnover.

A positive of superheads is that exam results do increase during their tenure. The average improvement is 9 per cent for each year they lead a school. But, as the graphic on the left shows, once the superhead has left, those figures crash – with an average 6 per cent dip immediately after their departure, and continuous declines for up to three further years.

Hill finds the pattern deeply regrettable: “When a school emerges from a period with a superhead, you’ve lost three years, sometimes longer, and you’ve spent a load of money you didn’t need to. You are now behind where you could have been both in terms of the impact on students but also on your community.”

Using school accounts, the researchers found that the cost of superhead salaries, plus consultants brought in to “clean up their mess” after departure, resulted in bills of between £350,000 and £1.8 million for each school.

The costs increased the longer heads were in place.

Ethical rules, signed at the start of the project, stop the researchers revealing the names of any academies involved. Teacher and pupils are all anonymous.

Schools doing well therefore cannot be showcased. At least one academy, Hill said, was building a sustainable model, but its results only increased incrementally. In the early years its success looked less impressive than if it had a superhead, but had turned out to be better over the full five years.

“Ofsted needs to realise the pressure and timescales it is putting people under. It is encouraging short-term behaviours that are damaging and not the long-term behaviours that are helpful”

Hill and Laker – with co-researchers Terry Hill and Richard Cuthbertson – will next use their data to look at different styles of leadership and their impact, as well as explaining what organisations with long-term success rates do differently.

In the meantime, however, the pair are adamant the use of superheads should stop.

What did the 21 superheads do to boost results?

21/21: excluded poor behaving students

21/21: focused on maths and English

20/21: moved outstanding teachers to year 11

19/21: persuaded parents to home school low-performing students

18/21: didn’t enter low-ability pupils into exams

What was the impact?

Short-term positive improvement: 9 per cent increase

Dip after departure: exam results fell 6 per cent and only started to increase three years later

Larger dip if in place for longer: if superhead was there for three years, the initial dip was 9 per cent

Better results without superheads: sustainable leaders had slower growth but avoided crashes

Main pic: Laura McInerney, Editor of Schools Week

The first school I cut my teeth in was on a tough council estate. It is 19 years since its first OFSTED put it into Special Measures. 1 Fresh Start 3 great new dynamic Heads (two of which were “managed” out) 1 acdemisation and 1 new building later it is ranked inadequate, having been rated good by OFSTED having been rated good in a couple of its previous incarnations.

No one seems to have taken the time and trouble to evaluate the impact of 6 Heads and three name changes over the last 20 years. Instead school evaluation and the effectiveness of accountability measures misevaluated over 3year OFSTED cycles or 5 political cycles.

Given that it is in OFSTED’s interest to keep fiddling with its criteria, and politicians to sound tough in order to prevent such evaluation it is hardly surprising that short term careerists hold so much sway.

Shocking and disgraceful. Public money wasted on such a scale. Points up admirably all that is wrong with the current “vision” for schools.

When you incentivise teaching in the same way that you incentivise banking you should not be surprised to see the same behaviour in schools that you see in banks.

I remember a self-styled superhead saying to me “You know Steve, it is admirable that you want the students to really understand maths, but we have found it best if we just bully them through their exams.”

There’s also another group of ‘superheads’ – those publicly held up by ministers as exemplars for others to follow. This roll call includes Sir Greg Martin (Durand), Sir Peter Birkett (Barnfield), both knighted for services to education; Sajid Raza, (Kings Science Academy), Greg Wallace (Best Start Foundation), Patricia Sowter (CHAT), Liam Nolan (Perry Beeches).

But the organisations they led have caused financial controversy. Raza, is on trial for fraud. Barnfield was sent Financial Notice to Improve (now lifted). CHAT, Perry Beeches and Durand have also received FNIs – Durand is also being investigated by the Charities Commission. Wallace resigned during investigations that he’d awarded a computer contract to someone close to him.

This raises a question about the judgement of those who publicly praised them and whether their government seal of approval was awarded just because they supported government education policies.

“A positive of superheads is that exam results do increase during their tenure” is it? I would challenge this in two ways (i) it is this simplistic quantitative approach to “success” that has underpinned much of the kinds of change reported and (ii) the exclusion, tampering with teaching, ‘persuading’ children to leave are the reasons for this ‘increase’ – you seem to have been fooled as much as those who have rewarded these charlatans (and worse as Janet outlines above). As the research shows this calls into question (i) the focus on systems that has obsessed politicians for the last years (and still is with the grammars question) and (ii) the use of the measurement systems we current use. Will the politicians listen? They have failed to do so far.