Some schools are at “breaking point” amid a widening gap between the schools with the most and fewest numbers of pupils with education, health and care plans, research warns.

The National Foundation for Educational Research’s (NFER) interim report explored the characteristics of schools with high proportions of pupils with SEND and spoke to nine councils about their experiences.

NFER said: “It is essential that government reforms the SEND system to promote greater consistency and equity.

“This includes ensuring that schools committed to inclusive practice are supported rather than penalised and that the system does not place disproportionate pressure on this serving higher numbers of pupils with SEND.”

Here’s what they found…

1. Uneven distribution in mainstream schools

Last academic year, primary schools in the top quartile for EHCP rates had, on average, six times as many pupils with plans as those in the lowest quartile (7 per cent compared to 1 per cent.)

This equates to an average of 17 pupils per school in the highest group, compared to three pupils in the lowest. In secondary schools, the rate was five times higher for the top group.

Since 2018-19, the gap in EHCP rates between schools with relatively few pupils with EHCPs and those with many widened by 1 percentage point for primaries and 0.8 in secondaries.

Similarly, for any SEND, the range between the 25th and 75th percentile increased by 0.8 and 0.4 respectively.

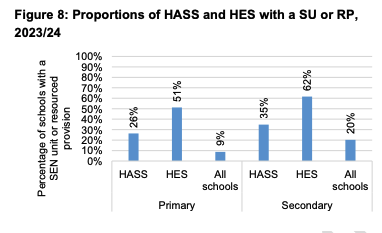

2. ‘High-EHCP’ schools more likely to have specialists units

Researchers identified two groups of schools. The first is schools with above-average proportions of pupils with EHCPs, compared to their local area and nationally. These were called “high EHCP schools” (HES).

The second is schools with high proportions of pupils with either EHCPs or SEN support – those without plans – called “high-any-SEND schools” (HASS).

Researchers compared SEND numbers to local area averages to account for contextual issues, such as pupils in certain areas being more likely to be issued an EHCP.

HES were found to be more likely to have a SEN unit or resourced provision.

But even when pupils in those units were removed from the data, two-fifths of the primary schools and half of secondaries were still identified as “high-SEND”.

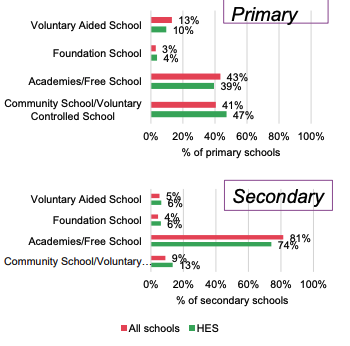

3. More likely to be a community school

Schools with more EHCP pupils were more likely to be a community or voluntary-controlled school, with academies slightly less likely to be in this group, the analysis found.

These schools are also less likely to be faith schools at primary, with only 26 per cent having religious affiliation compared to 37 per cent of all primaries.

Secondary HES are more likely to be in grammar school areas and small schools.

4. Lower levels of attainment, but similar Ofsted ratings

Compared to all schools, HES tend to have lower school-level attainment outcomes at key stage 2 and 4.

At primary, 30 per cent are in the lowest quintile for attainment, compared to 21 per cent of all schools. At secondary it is 26 per cent, compared to 20 per cent of all schools.

But there is very little difference between the two in terms of Ofsted judgments, NFER said.

HES are slightly less likely to receive an ‘outstanding’ judgement, but “broadly patterns are comparable”, NFER said.

However, HASS are less likely than HES and other schools to be rated ‘outstanding’, particularly at secondary level. These schools are also more likely to have either a ‘requires improvement’ or ‘inadequate’ judgement.

NFER said “schools who are struggling with quality of provision may also be more likely to over-identify SEND.

“However, it may also reflect that schools unable to secure EHCPs for pupils with the most complex needs face greater challenges overall, which in turn impacts their attainment and inspection outcomes.”

5. Primary HES more likely to be deprived

When looking at free school meal rates, 31 per cent of primary HES are in the most deprived quintile, compared to only nine per cent in the least deprived. But among secondary schools the pattern is less clear, NFER said.

HASS are more likely to be deprived than HES and all schools.

NFER said EHCP rates may be more likely to be understated in more deprived schools because families are less likely to have the financial means, social capital and capacity to ensure their child receives a plan.

6. Some schools at ‘breaking point’

NFER also interviewed 10 senior officers at nine councils about inclusion.

They said some schools were now “at breaking point” because of the uneven distribution. In some areas, a handful of mainstream secondaries were described as “saturated with EHCPs”, while others had far fewer.

One said a school was “almost becoming a special school… with a huge secondary school attached to it.”

Interviewees said parental choice and school ethos and reputation were the two “most significant drivers shaping how pupils with SEND are distributed across the system”.

Schools with strong inclusive leadership were seen to be “more attractive” and some schools “were content to let others take the lead when it came to supporting pupils with SEND”.

Other factors including school-level practices, accountability pressures and wider financial and structural dynamics were also reported to play a role, NFER said.

Inconsistencies in SEND identification was also important, something the Education Policy Institute also found several years ago.

In one area, the proportion of pupils receiving SEN support ranges from over 50 per cent in some primaries to as low as five per cent in others.

One interviewee said: “That is not because the cohorts are that different. It’s because if you had the same child in the school with 50 per cent, and placed them in the other school, they wouldn’t be on the SEN support register. They would just have their needs met through quality first teaching.”

Alongside wider challenges like funding and workforce constraints, uneven distribution “was reported to be generating tensions with LAs and across stakeholders”.

The challenges facing the wider education sector are becoming impossible to ignore, with outdated practices, under funding, and rising inequity affecting not just SEND pupils but the system as a whole. To understand why this matters so much, please take a moment to read our full letter: https://docmadeeasy.com/u/180169805.