School leaders in the region at the centre of the Trojan Horse scandal are less in favour of having to promote British values than their counterparts across the country, a new survey has revealed.

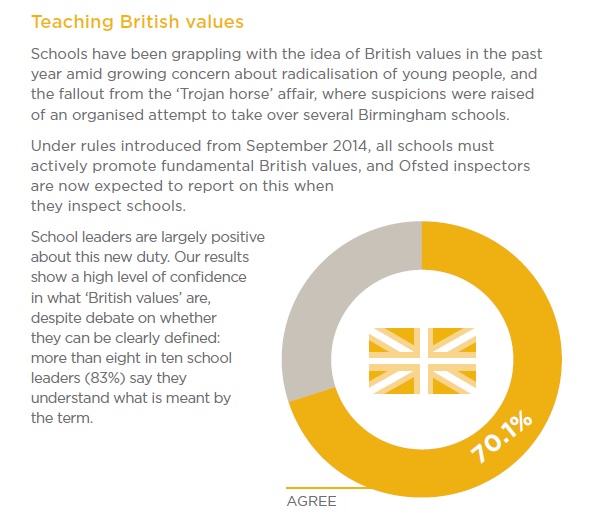

The State of Education report, published today by school leadership providers The Key, found only 58.7 per cent of school leaders in the West Midlands agreed that promoting British values was an appropriate role for schools – compared to 70 per cent nationally.

It was the lowest scoring region, with school leaders in neighbouring East Midlands the most likely (80.6 per cent) to agree.

Amy Cook, senior researcher at The Key, said: “British values are a real talking point for school leaders at the moment. We haven’t seen any resistance [from

schools] to this duty.

“Instead school leaders have sought guidance on how they can weave British values into the curriculum, for instance, and for pointers on inviting religious speakers into schools.

“So it makes sense to me that the majority of school leaders agree that promoting these values is a job for schools.”

A total of 80 per cent of the 1,180 heads, deputies and business managers surveyed said they understood what British values means.

Ms Cook said this was good news, adding: “Despite the debates in the media; perhaps this shows that, for most schools, this duty just reflects what was already happening on the ground.”

Multiple investigations were launched into Birmingham schools last year after allegations a group of hardline Islamists were plotting to take them over.

No evidence of a sustained plot was found, with little evidence of extremism of radicalism in schools.

But it led to the Government introducing new rules for schools to actively promote “fundamental British values”, with Ofsted also reporting on it.

The State of Education report read: “Schools leaders are largely positive about this new duty. Our results show a high level of confidence in what “British values” are.”

The report found that two thirds (66.2 per cent) of school leaders believed British values will help prepare pupils for life in modern Britain. One third (33.8 per cent) disagreed.

Imran Awan, senior lecturer in criminology and deputy director of the centre for applied criminology at Birmingham University, headed a study into the effects of the Trojan Horse scandal last year.

It found 90 per cent of the city’s Muslims felt community cohesion had been damaged as a result of the way the affair was handled.

Mr Awan told Schools Week: “A number of communities feel under official suspicion and feel alienated and marginalised [because of Trojan Horse].

“As a result, it appears that a number of leaders in the West Midlands are still feeling the consequences and impact of Trojan Horse more generally.”

Jacqueline Baxter, lecturer in social policy at The Open University, wrote for The Conversation: “Debates around incorporation of the policing of British values into the inspection schedule, Ofsted’s heavy-handed approach in policing them and the conflation of the whole idea of British values with the fight against extremism, are not going to disappear overnight.

“Nor are the accusations that what began as a failure of governance in 21 Birmingham schools has since been used to downgrade and close many others.

“In considering any future policies on accountability and oversight, the next government will have to think very carefully about what is to be done with the spectre of British values or wake up with a severe post-election hangover from the last administration’s policies.”

Your thoughts