The government’s phonics screening check needs an “urgent rethink” after new figures show “something dodgy” with scores, a policy expert has warned.

Figures published last week show 81 per cent of year 1 pupils met the “expected standard” in phonics checks this year, up from 77 per cent in 2015.

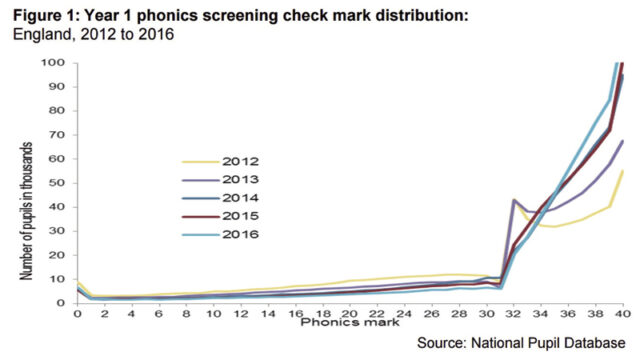

But the reliability of results has been questioned after mark distribution data showed a steep rise around the pass mark of 32 (see graph).

Data for key stage 1 teacher assessments, also published last week, shows fewer pupils reached the expected standard in writing last year, with 74 per cent of pupils at the expected level for reading.

Anne Heavey, education policy adviser at the Association of Teachers and Lecturers, said: “Sadly the phonics and key stage 1 results this year demonstrate one thing and one thing alone – something dodgy is going on with these assessments and they require an urgent rethink.”

This year’s phonics data showed the spike in pupils attaining the pass mark of 32 is actually less severe than the first two years of the test – when teachers were told the pass mark before the test.

The government now reveals the pass mark after the test, resulting in the spike smoothing out around the 32 mark.

Dorothy Bishop, a professor of developmental neuropsychology from the University of Oxford’s department of experimental psychology, told Schools Week the data reveals a “deep problem” that teachers “clearly don’t like classifying children on a ‘pass/fail’ basis”.

She said this could be down to concerns that such a tag could damage pupils psychologically, or that teachers’ own work may be evaluated on the results.

Along with the rise in year 1 scores, figures show the year 2 phonics pass rate also rose from 90 per cent in 2015, to 91 per cent this year.

The government has celebrated the rise, and academies have highlighted the value results offer for helping target intervention. But critics question the data’s reliability.

Russell Hobby, the general secretary of the National Association of Head Teachers, told Schools Week: “Any test that is used for accountability gradually loses its value as a diagnostic.

“The results of the phonics screening check are increasingly used in this way and therefore its ability to tell us anything meaningful about progress in early literacy is eroding.”

The data released last week also shows a continued underperformance in phonics of pupils eligible for free school meals or with special educational needs, and those from certain ethnic backgrounds, such as gypsy or Roma children, or those of Irish traveller heritage.

Bishop said that “any test result is imperfect” and that scores close to a pass-fail boundary are unreliable. But there is “some value” in identifying children who are “struggling with a key component of reading so that they can be given extra help”.

Heavey added: “It is time for ministers to accept that their new assessment system requires significant improvement, and must not be run again this year without major modifications.”

A Department for Education spokesperson said the government would take action if there was any evidence of maladministration.

No graph – but any teacher will get the picture. When an artificial number becomes an objective it alters priorities.

There is another perspective for viewing the results of the Year One Phonics Screening Check in a much more positive and professional light than a picture of hard-edged ‘accountability’.

It is that the results can inform teachers of the relative effectiveness of their phonics teaching which gives them a steer in whether they need to look more closely at how they are teaching phonics.

Any teacher should surely want to know if all his or her phonics provision, which includes the children’s phonics practice, is as effective as other teachers in like circumstances who perhaps might be doing something significantly ‘different’ with their phonics provision.

Even if the borderline marks are looking somewhat suspicious, nevertheless, the national mark of 81% is indicating that there are still 19% of children who may not be getting the right kind of phonics provision or even enough practice. There are over a thousand schools where nearly all the children are reaching or exceeding the 32 out of 40 benchmark and this number of schools is growing year on year.

Another issue that no-one seems to touch upon is that is it absolutely right than any government promoting, even funding, practices, programmes and decodable reading books tries to understand what difference this makes in our schools for teaching beginning reading. In other words, it is not only the teachers who are accountable but the people in authority who promote specific content and methods.

The greatest ‘diagnostic’ benefit to be gained from the advent of the Year One Phonics Screening Check is the look it provides us all in a responsible professional capacity. Foundational literacy is SO important, that it is a shame the check is not put forward in more positive terms.

The check is only a ‘snapshot’ of children’s technical decoding ability but it is simple and straightforward and invaluable for moving the country forwards in its CPD. In fact, the International Foundation for Effective Reading Instruction is promoting the use of the free check on a global basis wherever English is taught for reading and writing because the whole word would arguably benefit from a greater understanding of phonics teaching and teaching effectiveness.

The Screening Check was designed and constructed “to confirm that all children have learned phonic decoding to an age-appropriate standard. Children who have not reached this level should receive extra support from their school to

ensure they can improve their decoding skills, and will then have the opportunity to retake the phonics screening check.”

The Check “does what it says on the tin.” If there is any question about the reliability of the results for an individual child, there are now four “parallel forms” of the Check from previous administrations that can be used to remove any doubt that child needs “extra support.”

The “dodgy” considerations do not reside in the Check. They concern the instruction the children who don’t pass the Check are receiving. This “long tail” of the distribution includes 19% of students in Yr 1 and 9% in Yr 2. The wide variation reported among LEA’s and the fact that numerous schools enrolling “deprived” children are teaching “all” children successfully indicates that it’s “in the instruction,” not in the kids, the teachers, or the water.”

Unwarranted objections to the Check mis-direct attention away from investigation of the protocols and products being used in instruction. All schools and teachers “know what they are doing” and are very willing to tell anyone who asks. The methodology for sorting out the effective and ineffective products and protocols is easy and inexpensive. The potential results of such investigation threaten those at the top of the EdChain (those who are opposing the Check) rather than the teachers and students at the bottom of the Chain who find the Check “no problem.” How long it will take before this is recognized and the matter sorted out is anyone’s best guess.

It’s right that teachers assess pupils’ reading ability. As you say, literacy is fundamentally important. This should be going on all the time. But it should be done when appropriate and not wait for a government-mandated decoding check.

The teaching of reading is ultimately the responsibility of teachers. It is not up to politicians to promote or fund their pet programmes. It’s up to professionals to decide what is appropriate for their children. A DfE commissioned report in 2014 (not widely reported) found teachers were combining phonics with other methods. http://www.localschoolsnetwork.org.uk/2014/09/gibb-claims-rise-in-number-passing-screening-test-is-down-to-relentless-emphasis-on-phonics-but-dfe-commissioned-research-contradicts-this