People who run the New Schools Network (NSN) tend to move on to bigger, brighter, bluer things.

Its first director, Rachel Wolf, currently resides at No 10 as David Cameron’s education adviser. Number two – Natalie Evans – is a Conservative whip in the Lords. But director number three, Nick Timothy, has come the other way, moving into the role after a long stint as Theresa May’s adviser at the Home Office. Perhaps NSN is less a springboard to power than part of a revolving door.

The organisation is also controversial. Started in 2010 to promote new schools – read “free schools” – it was given a 50,000 grant by then-education secretary Michael Gove’s department without having to bid for it. A network spokesperson famously said that it would not be transparent about its dealings, stating the organisation had not “and never will” answer a freedom of information request. (That spokesperson was Dominic Cummings, who went on to become Gove’s adviser, yet more evidence of the revolving door.)

Opponents of free schools, and Conservative ministers, often complain about the cosiness of what they see as a cliquey political elite and, if you listen long enough, you can come to believe that everyone in it is a mal-intended grandiose aristocrat.

I haven’t done anything as remarkable as teach a class of kids

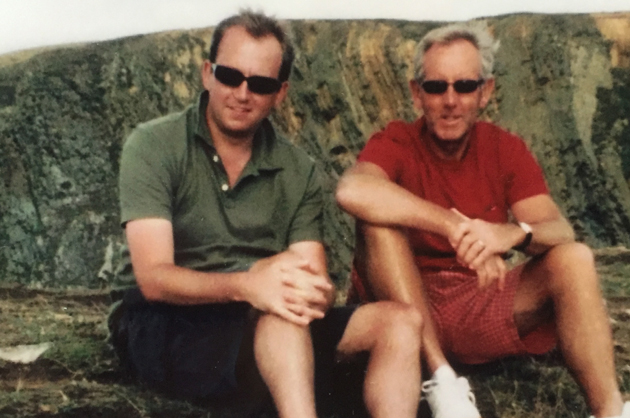

And then you hear Nick Timothy talk about his background. Growing up in Tile Cross, east Birmingham, he explains that his parents left school at 14. “Dad worked for a big steel and wire company, mum did secretarial-admin work for a local school and, when it became an academy, started to do more work on the pastoral side of things”.

He went to a Church of England primary, Shireston, and then to one of Birmingham’s King Edward grammar schools. “The Aston one.”

Using the language that people who work in politics use to talk about schools, he explains how his experience was “transformational”, how it “emphasised character” and he was “lucky with a lot of the teachers I had who were just extraordinarily brilliant teachers”.

It wasn’t teachers who inspired him to join the Conservative party at 17, but school did play a part.

Starting secondary school shortly before the 1992 general election, he became aware that Labour were unhappy about grammars. “I knew that if Labour won the election they’d have closed the school I’d just had the chance to go to.”

He believes grammars benefit “particular kinds of students” and is dismissive when I ask if there were other people from his primary school, who didn’t get in, who might also have benefited from the transformational school.

“If the purpose of the question is to ask whether I think a grammar school education detracts from the education of kids who don’t go to grammar schools, then no, I don’t.”

His adventure into party politics came while studying politics at the University of Sheffield, a place he chose because it wouldn’t be too expensive but was still in a city. Having enjoyed studying, he wanted to turn his hand to the real thing so wrote to the director of the Conservative party research department asking for a job.

His enthusiasm turns up a notch and he begins speaking in political colloquialism: “For some reason, they gave me a job, so I worked in CRD [Conservative Research Department] for . . . that was September 2001 to February 2004, and that was great. I did a range of different jobs, I was head of the political section, worked with Theresa [May] for a while, got to know David [Cameron], George [Osborne], and Boris [Johnson], because they were on IDS’ [Iain Duncan Smith’s] prime minister’s questions team and I helped with them.”

Leaving in 2004, “because I didn’t really think we were going to win the election”, he did a series of policy jobs in trade organisations before working for a year with Theresa May, then back to the research department and, finally, in 2010 entering the Home Office with May as her special adviser, which he did for five years.

It is a whirlwind career in the corridors of power, but how has it prepared him for heading an organisation that helps people to open schools?

“I’d be the first person to say that I haven’t worked in education, and I haven’t done anything as remarkable as teach a class of kids, to lead or run a school, but . . . my background shows that I have campaigning and policy and strategy skills, and those are appropriate for an organisation like NSN.”

He has visited many schools – about 50 – to “try to really get under the skin of what it takes to be a great teacher and a great school leader”.

Asked about what he has seen and the answers verge on trite: “My overwhelming reaction on this is actually to be incredibly impressed by the teachers and the pupils. They’re . . . I mean, teaching is a vocation, and people who decide to enter the profession are doing it not for the huge salaries that are on offer in certain parts of the private sector, but because they have a passion for helping young people, and that comes across in spades. It’s wonderful.”

When I ask if anything shocked or surprised him, he instead says what he thinks is “interesting” about schools (“everything moves forward”); when asked if austerity and tight capital budgets have derailed free schools, he talks about what is “encouraging” in the policy.

His years spent in campaigning clearly coming to the fore, he ducks and weaves skilfully, giving just enough information to make it sound like a question has been answered but bobbing back to the central message of the future.

So, what does he want to achieve in the future for New Schools Network?

The organisation will do more to help schools between approval and opening, he says, and garner the experience of the hundreds of free schools that are now open and share their knowledge.

“But more importantly,” he says, “I want us to return to our campaigning roots that we had when the organisation was first set up. So that means making the case for the free schools as a policy programme, but it also means trying to go out and help to identify the right kinds of people to come into the system and open great schools.”

To that end, NSN is opening a new office in Manchester and will focus on the West Midlands as a growth area too. The two areas are now being tracked by the Conservatives, who want to start winning back cities that have previously been Labour safe seats.

But Timothy scoffs when I suggest that his intentions might be coming from a party political place. When he challenges policy, he says, it is straightforwardly based on the policies and what works.

“If there’s a problem with the system then it needs to be fixed, and nine times out of ten, in fact, probably 99 times out of 100, there won’t even be the slightest hint of philosophical or party political element to it – it will be what’s right.”

More work in the West Midlands would, however, allow him to more easily get to see his beloved football team, Aston Villa.

He laughs when I ask how they are doing. They lost the day before, badly.

“I sometimes say to people that following football when it’s your local team, and you’re not just choosing the team for glory reasons, teaches you an important lesson in life, which is that sometimes, things just don’t get any better.”

And yet he’s loyal to them?

“Completely! If not to the current leader,” he laughs.

Theresa May might be pleased to hear that. Better start cranking that revolving door.

IT’S A PERSONAL THING

What book have you given as a gift or recommended most often?

I’m evangelical about Graham Greene. His interest in humanity and obviously his interest in religion define his writing, which is why I think he’s such an interesting person to read. Brighton Rock – the first I read – is my favourite.

If you could live in any historical period, what would you pick?

I might say the early 1900s when Villa won everything, but for most people almost any time in history is miserable compared with now.

A memorable party from when you were a child, or from youth

Probably a cousin’s wedding when I attracted more attention than I should have by getting quite drunk when I was 14. I uncharacteristically danced rather too much.

Describe the first two hours of your day

I’m constantly reading news and checking different news websites as I get ready, and then it’s a mad dash to be on time.

If you were invisible for the day, what would you do?

I would probably keep myself to myself because anything else would just be a bit weird.

CURRICULUM VITAE

Education

1986 – 1991: Shirestone Junior and Infants

1991-1998: King Edward VI Aston Grammar School for Boys

1998-2001: University of Sheffield

Career

2001-2004: Various roles, including head of political section, Conservative Research

2004-2005: Corporate affairs adviser, Corporation of London

2005-2006: Policy adviser, Association of British Insurers

2006-2007: Chief of staff, Theresa May MP

2007-2010: Deputy director, Conservative Research

2010-2015: Special adviser to the home secretary

2015 – present: Director, New Schools Network

What a prat.

Says the person with the name ‘Tarquin De Launcey’

Funny, I went to a King Edward VI Grammar school, and I’ve ALWAYS thought I’d have done better if I’d gone to a comprehensive! They were great for the really academic kids, but no use to anyone else, and their mindset was very narrow and blinkered.