In 2002 when she admitted that she wasn’t up to the job, former education secretary Estelle Morris did what politicians rarely do. She spoke her mind.

More than 12 years later, and now a Labour peer, she was as candid as ever when she joined an education panel at the Fabian Society’s new year conference at the Institute of Education.

Her intervention in favour of broad agreement between Labour and the Conservatives over school autonomy may not have shocked her Fabian colleagues, but is nevertheless significant in the wake of the recommendation from another former education secretary, David Blunkett, that local authorities be allowed to become “community trusts” and run academies.

Labour and the Tories need to “stop competing” over schools’ policy and make a “rigorous appraisal” of what the two could agree on, Estelle Morris told the conference.

Ms Morris, who served as education secretary from 2001 to 2002, said Labour should focus on what it disagreed with the Tories on, not on the common ground

“Where I think we would disagree, and ought not to let the Tories get away with it, is the state of the education system – with the emphasis on ‘system’. The notion of the free-standing academy ought not to be allowed; not the academy bit, the free-standing bit.”

Speaking to Schools Week after the conference, Ms Morris said: “The main point I was trying to make was that schools can’t survive and flourish alone. They have to be part of a wide group. They need interdependence as well as independence. Standalone academies don’t deliver this.

“I am not opposed to David Blunkett’s solution [the community trust model] but there may be others as well. The key thing is to start building up the partnerships and infrastructure that have been taken away.”

In her speech, Ms Morris said education had “fallen down the agenda”.

“For the past 20 years education has been top of the political agenda, but you now struggle to hear about it. I don’t think it made a mention in any of the leaders’ speeches at the party conferences.

“There’s a feeling that after 20 to 30 years of reform, we all now sort of agree that independence, autonomy and trusting teachers, strong accountability for direct framework at the centre and freedom out in schools, is the way forward.

“I would like to see a much more rigorous appraisal about what we can agree is the same [between parties], what we have learned and what we should build on, but a clear differentiation about where the dividing lines still are between left and right-wing politics.

“We can agree now that we can stop competing against each other, that heads should be autonomous to run their own show, that they should be able to set the values, that they should have the freedom. I think we all agree that it’s the quality of teaching and learning that matters in the classroom and not anything else.

“Tories and part of Labour, New Labour, have been very late in coming to realise that. I think we can agree that accountability is right, but there is a big question about the nature of the accountability. There are lots of things that are a firm foundation for us to build on.”

Estelle Morris Facts

• Education secretary between 8th June 2001 and 24th October 2002

• That’s 503 days in office. The average is 874.

• She taught for 18 years in a secondary school in Coventry before becoming an MP in 1992

• Her resignation was a surprise and several officials cried as she left her DfE office

• She said the job was too important to have someone who was “second best” at it

THE SPEECHES

Ros McMullen, Leaf Academy Trust chief executive and executive principal of David Young Community Academy, Leeds

“The link between poverty and educational under-achievement is a causal link, and the fact some children from disadvantaged backgrounds do extremely well doesn’t disguise this. It’s well-researched, it’s well-documented, it is beyond dispute.

“Of course the traditional response from the left was always to attempt to create a level playing field and every decade saw new initiatives for education, which was able to spend more money on the education of the most disadvantaged. But little changed, because children who are brought up in families that value education have home and school working together, and children who are brought up in families that do not value education have home and school working in opposition.

“Traditionally the poor have been educated by professionals who have chosen to do so from a real sense of social justice and service and a commitment to make a difference or, and let’s be entirely honest about this, people who weren’t actually very good at it, weren’t very well qualified and ended up in the worst schools.

“What that led us to was a culture in the schools that largely served disadvantaged communities. A culture of cuddle and muddle that was typified by the phrase ‘we’re very good pastorally’, which is rubbish because there’s nothing good pastorally about letting kids fail.

“The resistance to the standards agenda has come very largely from that traditional approach that emerged from the left, and we have got to be honest about that. Thankfully over the past 20 years or so that approach . . . has changed.”

Richard Brooks, former Ofsted director of strategy

“I want to talk about an area of the education system that we don’t generally focus too much attention on Ð the 14 to 19 end, which lots of people in the Labour movement care about a lot but which never makes the national news.

“[Some of] these people have been in full-time public education for 14 years, and we have failed to equip them with the skills and qualifications they need. It is a scandal, and it’s not something we talk about enough.

“I’m not going to say here’s the magic solution, but the four building blocks are more young people skilled in literacy and numeracy at 16, schools delivering on their core mission, careers advice that tells people what they actually need to do to succeed and employer engagement. Employers want to help, particularly with young people, but it’s incredibly confusing and difficult for them to do so at the moment. As a result, schools don’t have employer links, colleges aren’t properly engaged.

“The fourth part is about getting the quality of FE provision better . . . it’s only 230 or 240 of these institutions, and lots of them are, frankly, rubbish. They are huge public bureaucracies, sucking up public money and churning out young people who don’t have the skills and qualifications they need. It’s outrageous.

“The people who run them are paid always in excess of £100,000 a year. We should be angry about this, but because they’re below the radar, they get away with it by saying ‘these people are hard to help’ and ‘we’re doing the best we can’. It’s nonsense. They are failing to serve the very average-looking young people who want to get on in the way they should be served.”

Dr Patrick Roach, deputy general secretary of the NASUWT

“It may come as a bit of a surprise to hear me as a leader of a teachers’ union arguing about entitlement for children and young people, entitlement to quality education, but for us that is the big issue at the 2015 general election.

“It is the issue my members speak most vocally about as having undergone the greatest assault since 2010. We have witnessed since that period an attack on the right to quality education, the rolling back of entitlements that were cumulatively and progressively secured, dare I say, under both Labour and Conservative governments over the course of the past 70 years.

“There are still dividing lines between Labour and Conservative in the context of entitlement; of the right to be taught by qualified teachers, the right to quality education, to a broad and balanced curriculum, of not getting an education offer that’s constrained as a result of a narrow set of performance measures – which define what good education looks like.

“We have seen the abolition of the education maintenance allowance and now more freedoms and flexibilities for schools to charge for what are now deemed to be non-core aspects of education provision.

“For many young people, they are now being forced to make choices about what kind of route to follow based upon either their ability or their parents’ ability to pay.”

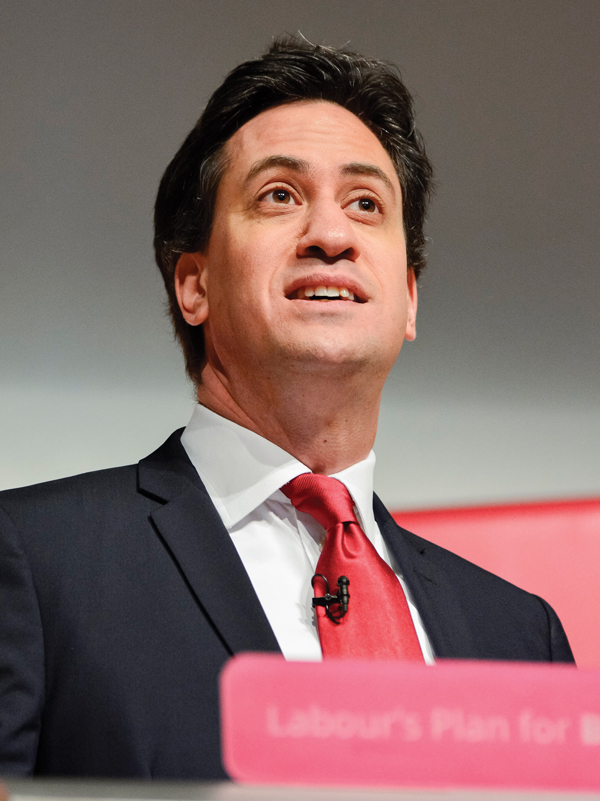

Miliband’s ‘inspiring’ education vision

Education featured prominently in Labour leader Ed Miliband’s speech to the Fabian Society conference.

Mr Miliband used much of his speech to attack the Tories, but also attempted to outline a vision for an education system under Labour.

He said: “To create the country we believe in, to build that future, young people will be at the heart of our plan.

“We judge the future of a country by the prospects for the young.

“I don’t think there has ever been a government that has so often made the young pay the price for hard times than this one.

“We will have a new direction. An education system that serves every child in our country: creative, inspiring, and doing what our country has never done: valuing vocational and academic qualifications equally.

“Every young person deserves a chance of a decent education after 18 and a career.”

Mr Miliband also criticised the government for falling numbers of apprenticeship starts for 16 to 19-year-olds and for raising university tuition fees.

Your thoughts