The pandemic-spurred boom in teacher recruitment has continued this year with the arrival of another wave of potential recruits. But, as schools are forced to limit on-site attendance amid a third lockdown, can they handle this influx of new trainees?

A Covid recruitment boost saw the number of people starting initial teacher training (ITT) courses rise by nearly a quarter in 2020-21. It meant, for the first time in eight years, that the government met its recruitment target for secondary school teachers.

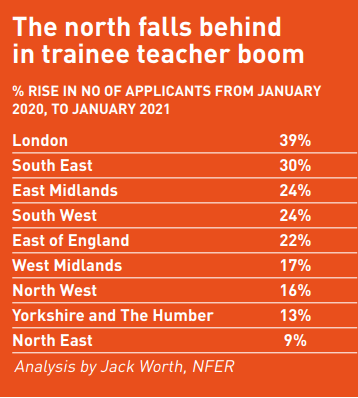

And the boom has continued into this year. Analysis by Jack Worth, a National Foundation for Educational Research economist, shows applications in January were up 26 per cent compared with the same time last year.

Government cuts to training bursaries – some by as much as 73 per cent with others scrapped altogether – has partially “dampened” the spike, Worth added, but still the numbers are significantly up.

Depending on teacher retention rates, the sector would most likely be in a “very healthy position” for the coming years, Worth said. The boom, however, is uneven.

Worth’s analysis shows London and the South-east picking up the most new teachers (39 per cent and 30 per cent respectively), while rises in northern regions are much more limited (see table).

And any spike in applications will challenge schools to provide placements for more students as part of their training courses.

ITT providers concerned about placements

Four-fifths of 247 ITT providers surveyed in June said they were more concerned about securing sufficient school placements for this year, compared with previous years. The University of Sunderland, which had 1,033 students on ITT courses this year and 815 last year, ran placement capacity audits at schools to manage the rise.

Professor Lynne McKenna, academic dean of the university’s Faculty of Education and Society, said this “enabled us to be confident of not only providing placement opportunities for students, it also was about using that intelligence to support filling the teacher supply needs of the region and beyond.

“Regular and consistent communications to school partnerships is key here, and by reassuring them about the benefits that hosting a trainee teacher can bring to their school, I am confident offers of placement opportunities will continue.”

Professor Sam Twistleton, director of the Sheffield Institute of Education, said schools have adapted “really well” to integrate trainees – despite the Covid problems. Sheffield has enrolled 1,554 trainee teachers this year, 19 per cent more than last year.

But Twistleton, who is also chair of the DfE’s ITT content group, added that she would be “interested” to see how the department could “incentivise” schools to take on placements at a higher volume.

How is technology helping?

The National Foundation for Educational Research estimated in July that Covid had slashed capacity for placements at primary schools by 20 per cent, and 7 per cent at secondaries. But schools have embraced technology to find innovative ways to host trainees – with some even taking on more than usual.

At the Great Schools Trust (GST), in the North-west, 80 students from two universities watch live lessons being delivered, with a debrief from either teachers or course leaders at the end of the day.

A survey of 141 school-based providers in October found that 92 per cent of trainees were already in a school. Only 8 per cent of placements were delayed until later in the autumn term, with one provider waiting until after Christmas.

Emma Hollis, executive director at the National Association of School-based Teacher Trainers, said the GST’s initiative could “absolutely” help those who have not successfully secured a placement. Technology could also, for example, give students studying in “leafy suburbia” the opportunity to experience classes in city centres.

The Department for Education has granted flexibility this year. Students no longer have to physically be in a school for 120 days. Usual rules to complete placements in two different schools have also been relaxed.

But department guidance “strongly” encourages schools to continue to host ITT trainees during lockdown, both on-site and helping with remote learning.

Trainees teaching live lessons

At Caistor Yarborough Academy in Lincolnshire, they are allowing students to stay on for a second placement if they have struggled to secure another. “As a school it allows consistency for us and the trainees, so we can continue to work with them and develop them,” said assistant head Simon Chadwick.

ITT students are also teaching live sessions online and helping to set work for students at home.

ITT students are also teaching live sessions online and helping to set work for students at home.

Chadwick said that, while he thinks students training during these times will be “very competent” in planning and delivering subject content, they may not be used to adapting to live situations and working with behaviour management.

Dr Andy Hind, head of secondary ITE at the University of Warwick, said Covid had “kicked us out of some of the routines and assumptions that we make about training. “It has made us look in a much more open and less closed-minded way at what can be done and what can benefit training.”

James Noble-Rogers, executive director of the Universities Council for the Education of Teachers, said that innovations “will be carried forward into the post-Covid world”. But he warned that the “underlying reasons why we face periodic teacher supply problems will remain.

“We must take care to protect the teacher supply base provided through existing teacher education partnerships.”

The DfE has launched a review to tackle the “overly complex” ITT market.

What the DfE said

Officials are considering what further interventions may be needed to support assessment of this year’s trainees and will provide information in due course.

Any changes from the ITT market review would be implemented after the pandemic abates, and focused on changes in the sector over the long term.

The “continued surge” in applications was “great” to see, but the priority remains “working with the sector to respond to the challenges they are facing due to Covid and enabling trainee teachers to continue their courses and enter the workforce.”

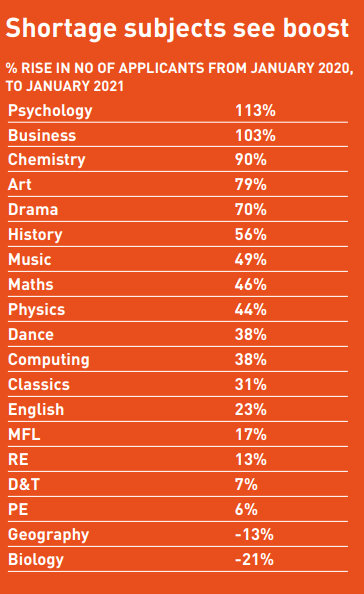

Please would you tell us what the target was for Mathematics and Physics teacher recruits and then actually how many were recruited. Telling us that there was a 46% and 44% increase in recruits from a pathetically poor level last year is hiding the fact that yet again we have failed to recruit enough Mathematics and Physics teachers – I believe the Government missed it’s target by 25% and 30% respectively but you would not know this from reading your article.