Teacher training is changing. After the release last week of figures giving numbers for those starting initial teacher training (ITT) this year, Schools Week takes a look at the different training routes, and the changes occurring in the training landscape.

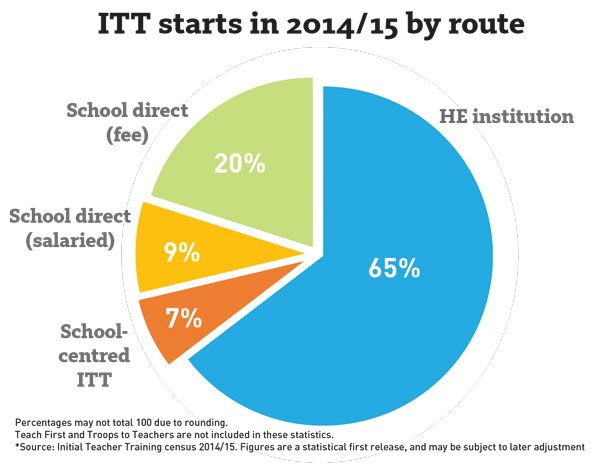

In September of this year, about 32,500 people started on one of the main initial teacher training routes: a course with a higher education institution; a school-centred initial teacher training; or one of the two School Direct routes.

All routes lead to qualified teacher status (QTS), but take different amounts of time, and offer a different mix of training experience.

There have been a number of changes in initial teacher training in recent years. The biggest of these has been a shift from provider-led training, such as that led by universities, to school-led training – something that the government has actively promoted.

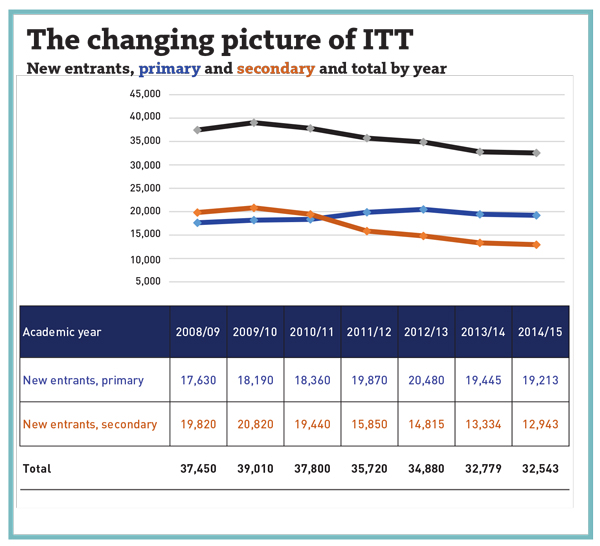

Since 2011/12 there have also been more people training as primary teachers than as secondary teachers – a reversal of the previous picture (see graph, right).

Problematically, though, government ITT recruitment targets have been missed for each of the past three years, prompting concerns about a growing teacher supply crisis.

Overall, the government recruited 93 per cent of its target figure this year – down on 94 per cent last year, and 98 per cent the year before.

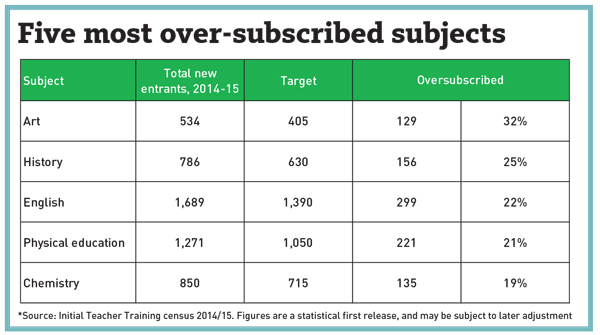

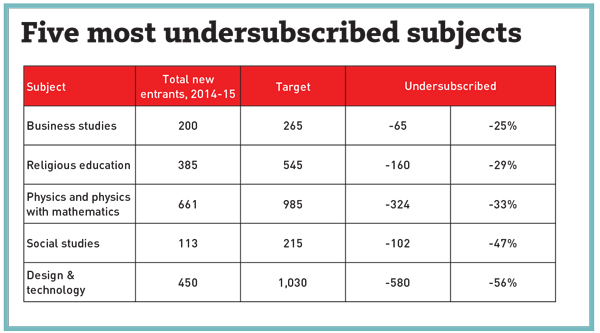

These headline figures mask a sharp variation in how closely recruitment targets have been met for individual subjects at secondary level.

This year, targets were surpassed in five subject areas, but in others, such as physics and design and technology, recruitment was well below the government’s hoped for level (see tables, right).

Different ITT routes have also seen varying levels of take-up.

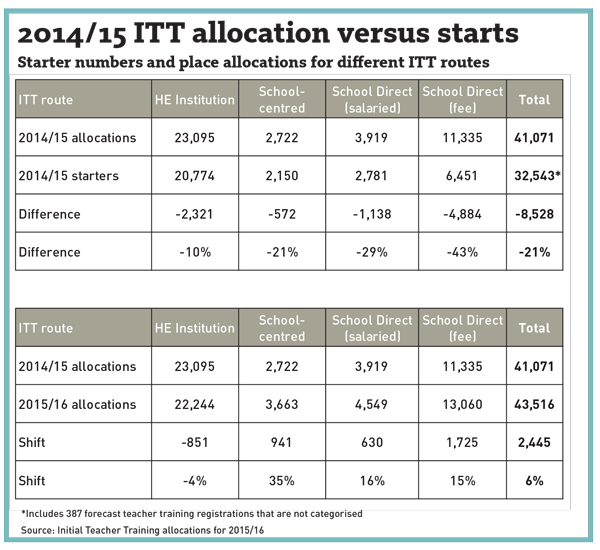

Each route is allocated a certain number of places by the government, with allocation levels always some way above the target figure, to account for some people not completing courses, or not finding work as a teacher after completing an ITT course.

Looking at these allocation figures, while the government has been keen to boost the number of people carrying out school-led training, School Direct has a much greater gap between the number of places allocated to it and the number of people who actually took them up..

TEACHER TRAINING ROUTES EXPLAINED

HE institution

The most popular route for gaining qualified teacher status remains a course completed at a higher education institution, with 20,774 people starting this provider-led route this September.

A Post-Graduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) course allows those with an undergraduate degree to gain qualified teacher status (QTS). Courses typically last one year when completed full-time.

For those who do not already have a degree, undergraduate study that leads to qualified teacher status is also available.

Unlike other ITT routes, the number of places allocated to training led by higher education institutions is lower next year than this year.

School-centred ITT

Schools that have been approved to deliver initial teacher training directly themselves are called school-centred initial teacher training (SCITT) providers.

SCITT courses generally last a year and see new starters receiving training from teachers at the school in which they are based.

According to the Department for Education, in many cases the training also leads to the award of a PGCE from a university.

This year, 2,150 people have started a course provided by one of these providers, against an allocation of 2,722 places – equal to 79 per cent of places being filled.

The allocation is set to increase to 3,663 next year, split roughly two-thirds to one third between secondary and primary.

Other (not in DfE ITT statistical release)

A number of other teacher training routes exist, but are not covered by the government’s latest training statistics.

Teach First is government-funded though independently run, and puts high-achieving graduates and career-changers into schools in low-income communities, following a condensed period of teacher training. Two thousand places have been allocated for the next academic year.

In September, private schools body, the Headmasters’ and Headmistresses’ Conference, announced that it would be launching HMC Teaching Training. The scheme will start next summer, offering a salaried, two-year training programme. Trainees will work in an HMC school while studying towards a PGCE from the University of Buckingham.

Troops to Teachers is the government’s school-based training route, leading to qualified teacher status, for people leaving the armed forces. Fewer than 100 service leavers started the two-year scheme in its first two cohorts this year, though the government has started an £8.7m tender to extend the process to 2018.

School Direct (fee)

School Direct is the main school-led training route, and has grown significantly since its launch in 2012, with 9,232 people starting the route this September.

Unlike school-centred initial teacher training, it is delivered by a partnership of a school or schools, and an accredited teacher training provider – a university or a school approved to carry out SCITT.

School Direct exists in two variants – a salaried route, and a route in which tuition fees are payable – with the fee-paying route the more common route (see below).

In both cases, trainees are recruited by one of the School Direct schools, and given on-the-job training generally lasting a year.

While its introduction has been the biggest change to teacher training options in recent years, across the salaried and fee-paying streams almost two in five (39 per cent) of placed allocated to School Direct have gone unfilled this year. For the fee-paying stream, this was 43 per cent.

School Direct (salaried)

Unlike the fee-paying School Direct route, the salaried School Direct option is generally aimed at those with three years’ experience of working somewhere else before starting training.

A total of 2,781 people started this route this autumn, meaning that 29 per cent of allocated places were not filled.

Trainees on this route are paid a salary by the school.

Teacher training – the key terms

QTS – Qualified teachers status. Teachers in free schools and, since 2012, new academies are not required to have or be working towards QTS – a topic of political controversy. Maintained schools can use non-QTS teacher in areas where – as teaching regulations put it – “special qualifications or experience or both” are required.

NQT – Newly qualified teacher. After a trainee secures qualified teacher status they must complete an induction period lasting three school terms, during which time they are a considered an NQT. Trainees’ performance during this period is assessed, and if judged to be of the required standard, they become a fully-fledged teacher, able to apply for work in any school in the country.

There is no set time limit in which an NQT must start or complete their induction period after gaining QTS.

PGCE – Post-Graduate Certificate in Education. The ‘traditional’ route to gaining QTS, a PGCE is a masters-level qualification issued by a university.

Trainees undertake placements in at least two school settings and study for periods at university.

At the end of the year students are assessed to ensure they meet QTS as well as PGCE requirements.

The politics of qualified status

Conservatives have remained firm in the view that QTS is a plus but should not be a requirement. “Heads are best-placed to make a decision about the qualifications, experience and knowledge that they need the teachers in their school to have.”

Nicky Morgan, 28 November 2014

Labour would require teachers to be at least working towards qualification. “Our starting point must be a commitment to ensuring that all teachers in our schools are qualified. So under a Labour Government, all teachers in state schools would have qualified teacher status or be working towards it.”

Tristram Hunt, 15 January 2014

The Liberal Democrats agree with Labour that teachers should be at least working towards qualification.

“I want every parent to know that their child will benefit from this kind of high quality teaching. That’s why I believe we should have qualified teachers in all our schools. That means free schools and academies too.”

Nick Clegg, 24 October 2013

Your thoughts