As local authorities grapple with rising SEND demand and mounting deficits – could locality clusters alleviate some of the pressure?

The funding model is being considered as part of government reforms to the special needs system, but what is it, and what are the benefits and risks? Schools Week investigates…

What is cluster funding?

Around 15 local authorities have adopted the “locality cluster” model of SEND funding, experts estimate. Other names for it include community funding or mainstream inclusion partnership.

Nottinghamshire has used a version since the 1980s while others, such as Kent, adopted the approach as recently as last month. And interest appears to be growing.

The model shifts high-needs funding from a ‘pupil-led’ approach – where access to cash mostly depends on a child securing an education, health and care plan – to a ‘school-led’ system.

Schools are grouped together and given a shared funding pot from their local authority’s high-needs budget, with leaders deciding how the cash is spent.

While practice varies, clusters are typically cross-phase groups of eight to 10 schools.

In Nottinghamshire, clusters control 18 per cent of the high-needs block, while in Hounslow, which launched clusters in 2023, they manage around 1 per cent.

Funding levels usually reflect metrics such as pupil numbers and deprivation levels, and SENCos, with parental consent, can apply for funding through their cluster.

Those SENCos then meet regularly – typically at least termly – to decide how to allocate money.

Faster, more flexible funding?

SEND policy consultant Dr Peter Gray, who has helped local authorities introduce the model, said it is “much more dynamic and flexible” and helps children access SEND support quicker than the EHCP route.

Although EHCP decisions should take no more than 20 weeks, last year 46 per cent took between 20-52 weeks, and seven per cent took over a year.

Pupils do not need an EHCP to access funding through clusters.

SENCos need only wait until the next meeting to make an application, rather than going through lengthy statutory processes.

Meanwhile, it can also help reduce EHCP cost pressures, Dr Gray added. If a child receives an EHCP at a young age, “it’s in the school’s interest to hang on to the resource once they’ve got it”.

But the cluster model helps gain access to shorter-term funding “to get you over a hurdle”, he said.

Jo-Anne Sanders, service director for learning and early support at Kirklees Council, added their cluster meetings also help primaries and secondaries “learn things from each other”.

Daniel Beck, strategic lead for SEND at Southampton Council, told us of a secondary that secured funding for Lexilenses reading aids – which help dyslexic children to read – for both for itself and all its feeder primaries.

This meant children arriving at the secondary had already “become used to using [them]”.

A way to reduce EHCPs?

One in 20 children in England have an EHCP, and one in five have special needs. Rising demand has led to huge deficits at councils.

South Gloucestershire Council introduced a cluster model in 2020-21. At the time, 3.5 per cent of pupils had EHCPs compared to 3.1 per cent nationally. Meanwhile SEN support rates were below-average.

A recent council report said local SEND leaders feel the clusters “have encouraged greater understanding, improved identification and collective responsibility for children with SEND”.

Its EHCP numbers have continued to grow, though more slowly than regionally or nationally – especially in primary schools where clusters are “more firmly established”. SEN support numbers have risen, narrowing the gap with the national rate.

Hounslow Council launched its mainstream inclusion partnership (MIP) in April 2023 to help reduce its SEND deficit under a safety valve agreement.

Head of service for standards, practice and partnerships Lyn Gray said the council is “constantly looking at whether we can invest more into this mainstream inclusion model”.

Cluster funding should not be EHCP ‘barrier’

Reducing EHCP reliance “is the dream scenario”, she added, but stressed there “are some children that do require that pathway” and the cluster model is “not a replacement as yet.” The idea is “to support children that maybe just need that early intervention”.

Nottinghamshire County Council, the earliest cluster model adopter, has still seen EHCP requests rise by more than 150 per cent to 1,719 in the five years to 2024. This compared to an England-wide rise of 87 per cent.

But it still has “one of the lowest number of EHCPs in the country”, said Orlaith Green, head of psychology and inclusion services, as children can access funding without one.

In some LAs, schools are now expected to seek cluster funding before EHCP referrals are considered.

But Abigail Hawkins, a former SENCo who now runs support service Sensible SENCo, said cluster funding should enable early intervention, and “not be used as the barrier to an EHCP”.

Supporting groups of pupils

Clusters often prioritise interventions that support several children rather than individuals.

In Southampton, around 86 per cent of requests made through the model have been “project-based” or “group” based, with only 14 per cent made for individuals. In Kent, its cluster funding scheme is limited solely to whole-school interventions.

Debbie Kelly, a former headteacher involved in establishing Kirklees’ cluster model, said her cluster initially focused on funding staff CPD, to “skill up more people to impact more children”.

In Hounslow, 60 per cent of funding applications have been for group initiatives, such as additional speech and language therapy and occupational therapy, learning mentor support, and creating “nurture spaces”.

Lyn Gray welcomed the shift “away from supporting just the individual”. But she noted the approach appears better suited to primaries. “You can pull children from classes in a primary and work in groups…[but] in a secondary school [that] won’t always work because of timetabling.”

Hounslow SENCo Georgie Venn-Coffey said her school secured funding for a teaching assistant to support year 2s who were struggling with reading, which “has been really successful”.

Another school used funding to train a therapy dog, while a secondary in Chiswick secured funding for a sensory space.

Abdicating responsibility?

But the model isn’t without its doubters.

One trust CEO, in a letter to Kent County Council, said cluster model “bids for funding for individual pupils are much less likely to be successful”, meaning schools will have to “compete with one another for much-needed funding”.

A Kent SENCo, who did not want to be named, added the model “feels like an attempt to solve a funding crisis without actually putting in more money”.

“The local authority is abdicating its responsibility [onto schools],” they added.

Kent County Council says the model “has significantly reduced bureaucracy and administration for both schools and the LA, so more staff time can be focused on delivering services where they are needed most.

“The model means school leaders, rather than KCC officers, are making more financial decisions. This decision-making needs to be well-managed, efficient and properly recorded, providing greater clarity and accountability for the use of public money.”

The council acknowledged the introduction of cluster funding is “a complex change”, adding it is “very aware the model needs to evolve further”.

But it said the aim is for “more timely responses to pupil need and strengthened SEND support, by maintaining the budget, but distributing in a different way”.

Professional development

Meanwhile, in areas where the model is established, SENCos appear to value it.

Orlaith Green said SENCos appreciate being able to “share practice” and “problem solve together”.

A recent survey of Hounslow SENCos found 72 per cent said discussions at cluster meetings had influenced their practice.

Meg Jones, headteacher at Kingsgate Primary School, Camden, said the model has “transformed” how children with SEND are supported locally.

“By allowing SENCos to apply directly to a panel of peers, we’ve reduced delays and responded more quickly and effectively, without relying solely on the EHCP process,” she said.

“SENCos feel trusted and empowered and families benefit from faster, more coordinated support.”

In Kirklees, an anonymous survey carried out after the cluster model’s first year found 90 per cent of SENCos supported it.

Dr Gray said SENCos “don’t just fight each other… for the betterment of their own school. They recognise that some children have bigger needs than others at different times, and we’ve got to have some local, collective responsibility for meeting needs across the broader area”.

Lack of uniformity

But without legislation or national guidance, consistency of decisions is problematic.

“I can submit two applications of equal quality, yet one may be accepted for assessment while the other is declined,” said the Kent SENCo.

Hawkins also warned the system could “pit SENCos against each other” with personal politics sometimes influencing outcomes.

And Green added any “breakdown in relationships” between SENCos “affects the consistency” of funding decisions.

To address this, some LAs have introduced quality assurance measures such as annual moderation, or cluster leads who coordinate decision-making and support applications.

But Hawkins argued the model “needs definition” and “consistency” between LAs, calling for clarity on “where it sits within all of those layers of funding”.

Green agreed a “consistent approach across the whole country” would help, particularly for SENCos working across multiple local systems.

Accountability needed

Benedicte Yue, chief financial officer at River Learning Trust, said “some form of accountability” is essential.

“When you devolve funding, you need a way to hold people to account,” she said, calling for reporting mechanisms to track how clusters operate.

An Ofsted area SEND inspection in October described Hounslow’s MIP as “successful” and improving children’s experiences through improved communication between schools and services.

But inspectors said the local area “does not have a strong oversight of how well education providers use their allocated funding”.

Yue believes an “intermediary mechanism” is needed to reduce “variability between the clusters” and provide “quality assurance”.

And Dr Gray hopes to see “regional communities of practices” formed so LAs can work together to implement cluster funding, and offer “constructive peer support and challenge”.

The government is understood to be interested in the cluster model as it prepares to reveal SEND reforms this term.

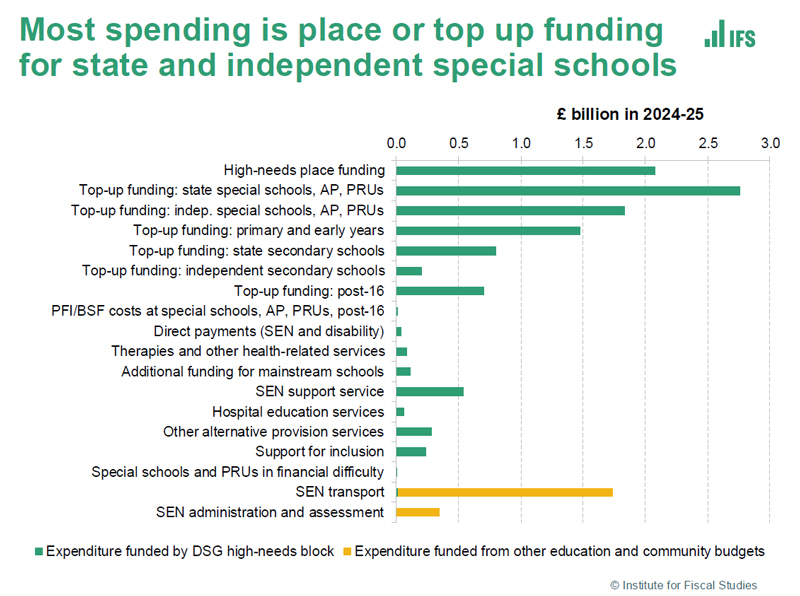

It currently spends around £12 billion on high-needs funding, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies. But DfE data suggests just £2.4bn was given to schools in SEN funding in 2023-24.

Around £2 billion is spent on SEND transport, with another £1.8 billion on placing children in independent SEND schools (despite just five per cent of pupils with EHCPs attending such schools), estimates suggest.

“At the moment the whole high-needs block is completely saturated [and] locked into statutory requirements for EHCPs,” said Yue. “There is no money left for early intervention.

“The idea of the cluster is to give less money to EHCPs – because we don’t think the individual funding is an appropriate model when you’ve had such an increase in complex needs.”

‘We could be getting great value’

Sanders, at Kirklees Council, said they have 230 youngsters costing £30 million in private SEND schools.

“If we can reduce that number because we’ve got the right capacity and skill in our state funded sector, then we’re getting value for money.”

The council also gained the “confidence of parents and carers” by involving parent and carer forums in developing their model.

Dr Gray pointed out that as authorities’ deficits are continuing to grow anyway without intervention, the hope is allocating funding via clusters will help reduce other spending long-term.

It does not mean “get[ting] rid of the statutory framework”, but “moves towards there being less need for that model because people are more confident in an alternative”.

He added: “It’s not a perfect system, it’s a developing system, but it’s one that’s got the most potential in terms of addressing the mess we’re in at the moment.”

Worked with Nottinghamshire on this . The main issue is the clusters run out of money so kids are left waiting for next academic year to see if funding available