The government’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) has finally published the advice it provided to ministers over plans to reopen schools.

Here are eight things we learned from reading them.

1. We’re still in the dark about the impact on children

The dossier of evidence includes a report on the role of children in transmission of COVID-19.

This document states that there is “a consensus that evidence on the role of children in transmission ofCOVID-19 is unclear, with a number of gaps in understanding”.

Children “typically present with milder symptoms of COVID-19 than adults”, but there is a “significant lack of high-quality evidence on the relative susceptibility, estimated asymptomatic fraction and relative infectivity of children”.

The paper points to “some evidence to suggest that children are as susceptible to COVID-19 infection as adults”, but warns that it isn’t conclusive.

2. DfE went to scientists with 9 possible scenarios

A second report, modelling and behavioural science responses to scenarios for relaxing school closures, goes into detail about the proposals the Department for Education asked scientists to model for the reopening of schools.

They were as follows:

- Stay shut

- Increasing attendance of vulnerable children and key worker kids to 11 per cent

- Transition years 5, 6, 10, 12, this side of the summer holidays

- The return of all early years settings

- All primary

- All secondary

- Half time rota system based on alternating weeks or fortnights

- Half time rota system based on alternating half days

- Full reopening

The government’s current proposal, that reception, year 1 and year 6 pupils return to primary schools on June 1 and year 10 and 12 pupils are given “some face to face support” in secondaries, was not among those modelled.

3. Ministers rejected rotas model, despite potential merits

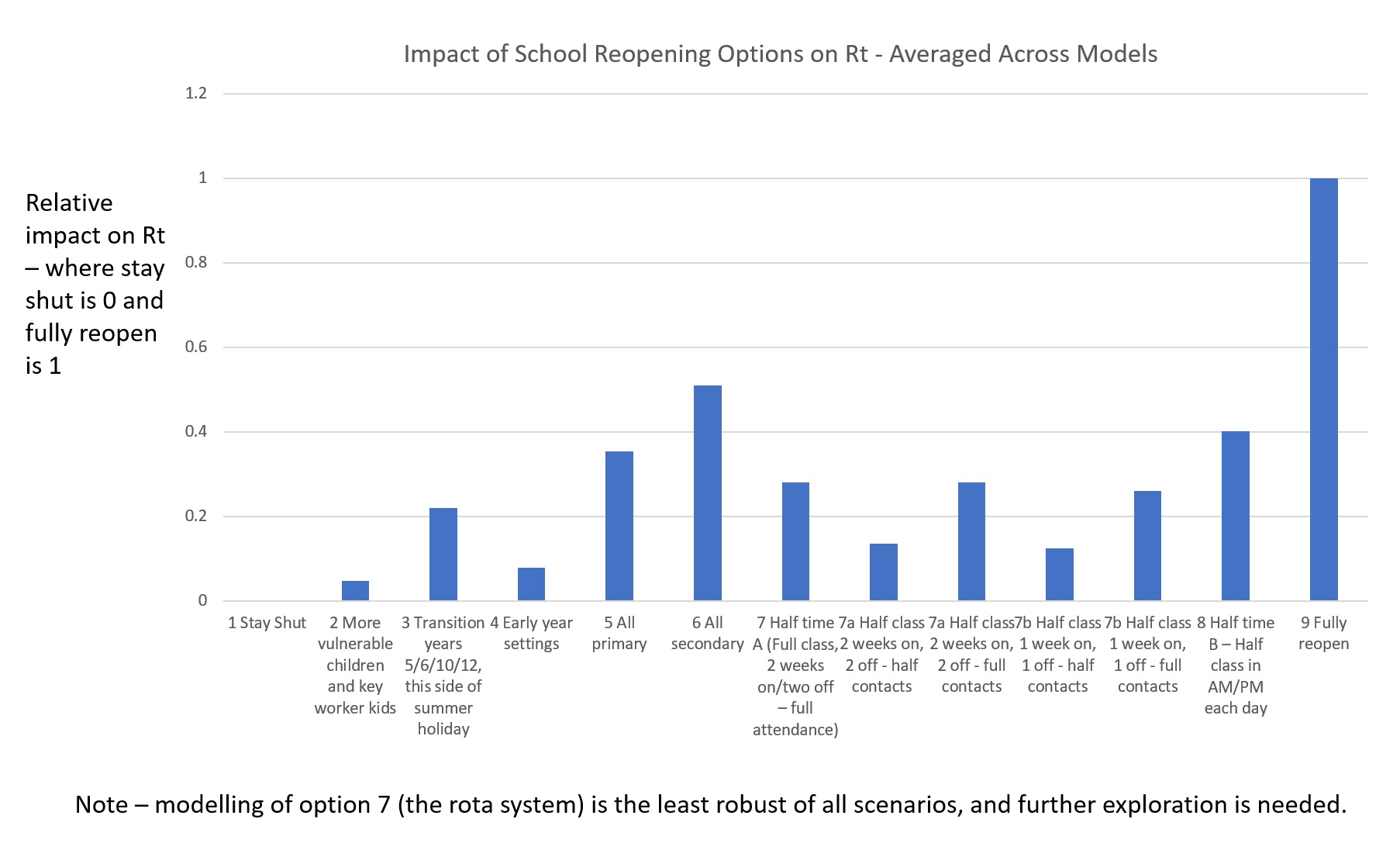

Although scenarios 2 and 4 were estimated to have the smallest impact on the infection rate, scientists also wrote about the potential merits of scenario 7.

Such an approach “may be a good way to stop extensive transmission chains in schools”, the advice states. “When this effect in schools is embedded into the wider community, the impact is less strong, but still has some value in reducing overall R”.

However, the document states that the modelling of scenario 7 “is the least robust of the scenarios, and further exploration is needed”, and does raise some potential pitfalls.

For example, parents of younger children “may not be able to align their working time with the rota system or may be sceptical of the limited school offer”.

The DfE said today that it had considered the merits of such an approach, but had decided not to use it because of the potential impact on parents, vulnerable children who would be in schools all the time, and schools themselves, which would have to clean between cohorts.

4. Forcing vulnerable children to attend would be ‘unwise’

According to the modelling document, scientists were aware of “suggestions that vulnerable children should be compelled to attend schools”.

The government has been keen to see attendance rise among vulnerable pupils, the vast majority of whom have stayed home for the duration of partial closures.

But scientists advised government any move to compel them to attend would be “unwise, firstly because these are a diverse group only some of whom may be at increased risk of harm at home, and secondly because in all but a minority of cases the harms in terms of alienating parents and stigmatising children would outweigh any benefits”.

“Additionally, SEND children could need intimate/close care from teachers/staff which makes social distancing difficult.”

5. Schools will have to think about timetables and site layout

The modelling document states that increasing the proportion of time outside “could reduce transmission”, assuming it allowed more distancing. However, social distancing is “more likely in secondary than primary or early year settings,” the scientists accepted.

Schools may “prefer to simply reduce the total time in school and remove or reduce break times”, the advice states, but this “might not be an option for early years settings or in settings with more vulnerable children”.

The documents also state that physical distancing between children, staff and children and staff “will be influenced by the physical design of the indoor and outdoor spaces and temporal management – to affect both flow of people and congregation inside and outside buildings”.

“Additional work is required to develop plans for redesigning shared indoor and outdoor spaces to minimise COVID-19 transmission.”

The advice adds: “The staff should move between classrooms, the students should not.”

6. Concerns over BAME pupils and teenagers

Households with black, Asian and minority ethnic or young adult members “may create greater susceptibility among children to the virus for different reasons”, the advice states.

BAME individuals “may be more susceptible because of the greater prevalence of frontline medical and care work”, while adolescents “may be more susceptible because they may not comply to regulations on social distancing and hygiene due to distrust of authority”.

7. What happens outside schools is important too

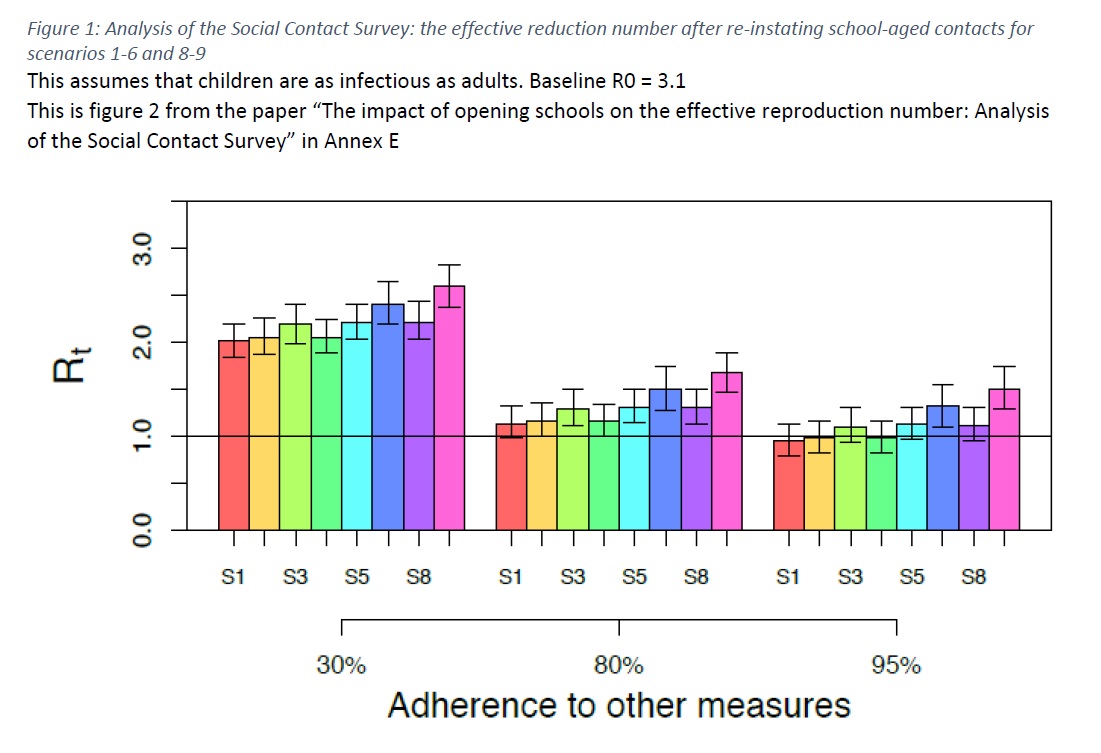

The advice states that although the choice of scenario for relaxing school closures is important, adherence to other social distancing measures is “a more critical issue”, as demonstrated by this graph.

The documents state: “If relaxing school closures results in falling adherence to existing social distancing and other measures (for example, through increasing adult work contacts), then this will reduce the scope for its implementation.

8. Teachers, parents and students should be consulted on messaging

Scientists advised the government that messaging to teachers, parents and students had to be “robust” in order to “enhance confidence and willingness to return”.

This messaging “will play an important role in each scenario”, and additional work is required “to identify perceptions of risk, understanding, and information needs across these groups”.

“Most importantly, these groups must perceive that the risk of infection is low before they will be willing to attend or send their children to school.”

The scientists told the government that messages “should be developed in partnership with teachers, parents, and students”.

As a primary school teacher in her 50’s with an older partner at home, I am very concerned about the reopening of schools. It seems to me that there are those who want schools to open for the sake of the economy. Those who want schools to ‘do their bit’ and ‘stand up’ and I think this emotive language is very clever however, I have noticed that recently many friends, neighbours, family, don’t want to meet (at a distance even) with me as I have been into school recently…. So, it’s ok for the school staff to go in and take these risks (risks not yet explained by the science) but no one wants to sit next to a teacher on the bus anymore or even on a very long bench. Interesting.

I agree totally with above comment. There is a lot of press about postal workers shop workers etc still working and school staff need to be joining them. Well schools have been open, and staff have gone over and above to keep life as normal for the children as possible, but they are in a class of up to 15,from 8.30 until approx 3pm daily. If being with a possible infected individual is higher because of spending longer than 15 minutes in their company, surely school staff are at a much greater risk. On the 1st of June, there will be little teaching, but at least the parents can help save the economy by going back to work. Disgraceful attitude from the government.

Do you have a link to the paper where this quote is from?

“may be more susceptible because they may not comply to regulations on social distancing and hygiene due to distrust of authority”.