In this age of mission-led government, ministers could learn a thing or two from Steve Chalke. They talk to him, but are they asking the right questions?

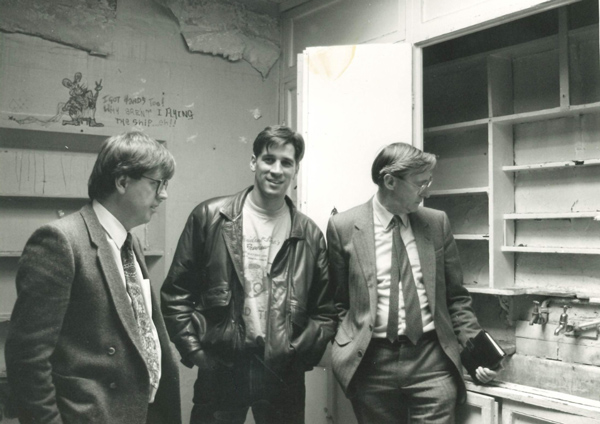

Chalke was a close friend of the last Labour administration, helping Tony Blair and then-schools minister Andrew Adonis hash out the academies policy.

Today, with 54 schools, Oasis Community Learning is one of the largest multi-academy trusts in the country. Oasis also runs the country’s first and only secure school, Oasis Restore.

The MAT is just one arm of the globe-spanning Oasis Charitable Trust, which Chalke and his wife set up 40 years ago following his childhood vision.

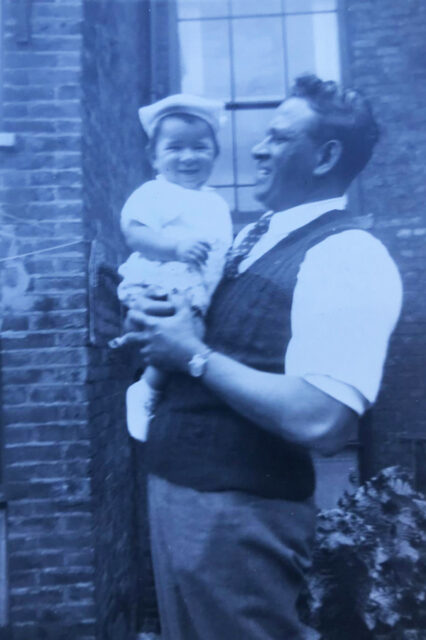

Born in 1955 in Croydon to an English mother (Ada) and an Indian father (Victor), Chalke’s childhood was marred by racism.

“People would literally cross the road” when Victor walked him home from school.

Victor had come to England in the late 1940s “to help rebuild Britain, in the same way as the Windrush generation” but “the invitation was bigger than the welcome”.

Even members of his mother’s family made life difficult for them because “they didn’t take to this dark-skinned brown guy”. Chalke went through his school years with the nickname “half-caste”.

His childhood was defined by poverty too, “in a house with no heating, no hot water. We never went on holiday. I never went in a restaurant.”

That childhood fed into what Oasis has become, he says. “There’s a passion to include people.”

With poverty came low aspirations. Having failed the 11+ (which everyone in the local authority sat at that time), he was sent to the local secondary modern.

“On the first day, we were told in an assembly we’d never do O-levels because we weren’t worth educating academically.”

The predictable outcomes resonate with today’s attendance and mental health crises. “A load of kids would never come,” he says. “A lot of my friends struggled altogether.”

Chalke kept on with school, but stopped going to church, only going back to its youth club again because a girl he liked was attending.

A few Fridays later, she rejected him. On the way home, mortified, Chalke’s life mission came to him, as “a gift”.

Mission statement

He was mulling never attending the church again when “I had this thought: At school they tell us we won’t amount to much, and at the youth club they tell us our lives have purpose.”

He decided two things: he was “going to believe the church’s story” and he was going to be “a Christian and a church leader”.

In that moment he set himself three further goals: to start a school “worth going to, because my school wasn’t”, to start a house for “kids who no-one cares about”, like his friends, to start a hospital. His local one in Croydon – May Day – was known as “May Die”.

When he got home, he told his mum about his revelation. “Very nice,’ she said. “And that’s the only piece of careers advice I ever got.”

It’s a mantra for Chalke: “a school, a house and a hospital”. As he tells me his story, I’m gripped by this example of the power of a moment to shape a life.

And if there’s a mantra that sustains the education system, it is surely this. Every education minister and every teaching ad relies on it to an extent: the teachers that inspired them, the fulfilment of the profession.

But perennial crises of workload, recruitment and retention attest to the challenge of aligning vision with reality.

So if mission-led government is the solution, then what does delivering the “opportunity mission” entail?

Mission launch

Set on his mission, Chalke took the opportunities that presented themselves. First of these was to run a youth group at a church on the rough Stanhope estate in Ashford, Kent.

“People called it Stanhope, no hope,” he recalls.

“So that’s what I did. At the age of 18, I went to live in Kent. I got a job as a factory sweeper and I used the money I got to run the youth group.”

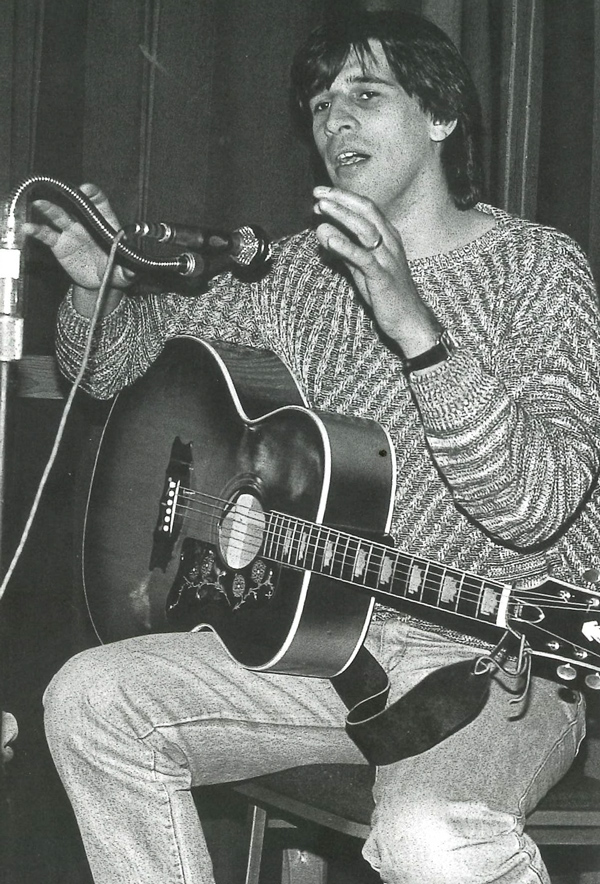

Around the hard, unionised labour of the day job, he set up a theatre company called Shout, putting on productions with and for the kids on the estate.

At 20, deemed “too young and naïve” to study to be a minister. he was sent to work at another church in Gravesend for a year. “I actually got to work as a youth worker there, which was great.”

At 21, he began training to become a Baptist minister at Spurgeon’s College, working as a youth worker in Tonbridge as he went. He was ordained four years later.

“But then I said: I’ve got to leave, because I’ve got to set up a school and a hospital and a house.”

For the next three years, he persuaded estate agents to give him disused shops for a few weeks at a time and set up pop-up restaurants in them with youth groups.

“We used to call them ‘eat less, pay more’ restaurants.

“The first projects in Oasis were to do that kind of thing. We ran hundreds of these restaurants, because I gave people the template to do it. We raised about £7 million and gave it all to a development agency, Tearfund.”

Mission control

Oasis got its name from Chalke’s wife, Cornelia, a Hungarian child refugee who’d lived just up the road from him.

She fully bought into her husband’s vision and worked with him on the plan. Establishing the house would be the easiest of the three aims, so that was first.

At 29, with “no money, no contacts and no credibility”, that’s what they set out to do.

“It was a painful experience,” he reveals, but “eventually, through a miracle” they were able to buy a house in Peckham, “which is where I wanted the first one to be.”

The miracle came in the form of Edna Scroggie (daughter of Baptist author and Spurgeon’s alumnus, W. Graham Scroggie). She and her husband had heard Chalke give a talk, during which he’d mentioned his vision of “a house and a school and a hospital”.

One evening, Edna called. “We’ve got a house and £10,000 in a bank account and we’d like to give you both,” they told him.

“But the problem was the house was in a leafy part of Croydon.” Not Peckham, where he was determined the house should be. Without ever even seeing it, he politely turned her down.

A couple of weeks later, Edna called back. Declining their offer made Chalke all the more worthy of it in their eyes, she explained, so they sold the house and gave his nascent charity the money to make his vision a reality.

As they worked towards the opening, Cornelia said one day: “It’s like we’re creating an oasis for these girls.” The charity had found its name.

Opened in 1987, Oasis still runs Number 3 in Peckham, which houses homeless young women. “In fact, we’re responsible for all the supported housing for over-16s across the borough of Southwark.”

Faith in the mission

Now with a name for himself in youth work, Chalke was invited to India to give lectures for the YMCA. Raised on his dad’s account of “a place of absolute beauty”, the poverty he encountered, “watching people die on the streets… blew all my theology away”.

He had “a giant crisis of faith”, but came back determined that Oasis would work in India.

Chalke’s first schools quickly followed, in Indian slums. “It’s easy to do when the DfE isn’t involved,” he laughs. “You hire a shack, put up a sign saying ‘School. Starts Monday. Free.’ And boom, you’re full. That’s your admissions process.”

Today, there are Oasis schools all over India and Africa as well as England. And jokes aside, there’s an important lesson for Labour’s school improvement drive here.

“We work in Dheravee (the slum made famous by Slumdog Millionaire). Nothing works in Dheravee, so the thought that you might run a school that produces perfection on its own doesn’t even enter their head.

“Sometimes it feels like we’ve not learned that lesson.”

Mission: Possible

In 1993, GMTV “decided to do an outside broadcast”. Near their studios was an Oasis project providing support for the homeless, so they went to visit and interviewed Chalke.

“I got a call the next day because they wanted to offer me a job.”

Chalke was propelled to TV stardom as the show’s in-house vicar, “doing all the social stuff” alongside Anthea Turner and Mr Motivator.

When a devastating earthquake hit the Indian region of Maharashtra region that year, Chalke persuaded the show’s producers to let him run a telethon. Grudgingly given a daily five-minute slot for a week, he raised over £1,000,000.

“That goes a long way in India, and it was enough to build a hospital.” Oasis delivers a lot of healthcare in a lot of hospitals, “but the only hospital we’ve ever built is that one in India.”

A church leader. A house. A school. A hospital.

Mission accomplished. But Chalke was far from done.

Waterloo perhaps best typifies his vision. In 2003, the charity became responsible for Christ Church and Upton Chapel, now Oasis Church Waterloo.

In the 22 years since, the area around it has become a vast complex of community organisations – schools, a children’s centre, adult community learning and much more.

In short, the opportunity mission can’t be delivered by schools alone. Mission-led government implies an ethical heart to policymaking – a vision.

Sadly for Labour, Chalke advises that “vision and frustration are the same thing”. Each is founded on a sense of “longing for, hoping for, praying for what has not happened yet”.

A little under a year into the Labour government, the opportunity mission has certainly brought a fair few frustrations.

And the best measure of its progress may be how many still have faith in it. Do you?

Your thoughts