We analysed over 250 academy trust accounts for Schools Week’s annual CEO pay league table investigation – here’s what we found …

Fewer than one in five academy trusts that were warned over high levels of pay subsequently reduced salaries for their top bosses.

The annual Schools Week analysis of chief executive pay also found 20 trusts where pay was hiked by £20,000 or more, with a single-school trust boss getting a £35,000 bonus.

The findings suggest the government’s crackdown on chief executive pay isn’t working.

The number of bosses paid over £200,000 has risen to 23, up from 21 in last year’s analysis.

The scandal of excessive CEO pay continues unabated

Furthermore, nearly a quarter of trusts who have been warned multiple times over pay have also hiked salaries.

But there have been changes. The one-school Knole Academy Trust, for instance, appointed a new CEO on a whopping £125,000 less than their predecessor.

Dr Mary Bousted, joint general secretary of the National Education Union, said the “scandal of excessive CEO pay continues unabated” and urged the government to “take much firmer action”.

The government has previously said ministers have no power to intervene and are reliant on the “good will” of trusts to slash salaries.

The Department for Education said they are now reviewing accounts to inform this year’s pay strategy. This will include “assessing commitments made by trusts in earlier rounds of high pay” and will take into account financial and educational performance.

What crackdown? Bosses still get rises

Since 2017, the Education and Skills Funding Agency has sent letters to academy trusts that have a staff member who is paid above £150,000, or multiple salaries of between £100,000 and £150,000, asking for justification, with evidence, for paying such high salaries from taxpayers’ cash.

Our analysis is based on the 277 trusts we identified that had received a letter. Thirteen trusts had either closed or had not published accounts yet, leaving 264 trusts.

Of those, 124 (45 per cent) saw pay rise for their highest-paid employee between 2017-18 and 2018-19.

One-third (92) had seen no change, while just 18 per cent (49) saw pay fall.

However, the number of bosses paid £150,000 or more dropped from 129 to 117 in the same period.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said executive pay is a “thorny and complex issue… Trust boards have to ensure that these often-demanding roles are appropriately rewarded while under perfectly legitimate public scrutiny about the value-for-money of their decision making.”

He urged trusts to follow National Governance Association guidance stating pay must be “affordable and sustainable in the long term, and appropriate for the level of responsibility”.

1 in 4 repeat offenders hike pay

Nearly a quarter of the 58 trusts that received two warnings from the DfE over high pay still increased salaries.

But, 24 per cent reduced pay, while just over half made no change to salaries.

Valley Invicta Academies Trust, which has eight schools, saw the minimum pay jump from £150,001 in 2017-18 to £200,001 in 2018-19. It had two joint CEOs until June last year, when one of them took over as sole CEO.

At Paradigm Trust, which has six schools, its highest paid member of staff earned between £180,001 to £190,000 last year, up from £160,001 to £170,000 in 2017-18.

A trust spokesperson said the two years are “not comparable” as chief executive Bill Holledge was given a promotion from interim chief operating officer to full-time CEO. They added: “An uplift with promotion is not unusual.”

The one-school trust Holland Park School, in west London, also saw a rise. Head Colin Hall’s pay rose by £10,000 to at least £270,000 last year.

Bousted (pictured) said that while some trusts have responded to government pressure, “other CEOs continue to receive unjustifiable salaries… Funding is for pupils, not over-inflated salaries for CEOs. The DfE needs to take much firmer action and introduce national provisions on MAT CEOs’ pay.”

Of the trusts that decreased pay, one-school Knole Academy Trust led the way. Accounts show former principal Mary Boyle, who retired at the end of 2018, was paid between £205,000 and £210,000 in 2017-18. She was replaced by David Collins, who is now paid £80,001 to £90,001, according to accounts.

Theresa Homewood, trust chair of governors, said: “When recruiting [Boyle’s] successor, governors took the opportunity to align the salary of the head teacher with national pay scales. The current governing body scrutinises spending carefully to ensure prudent use of financial resources.”

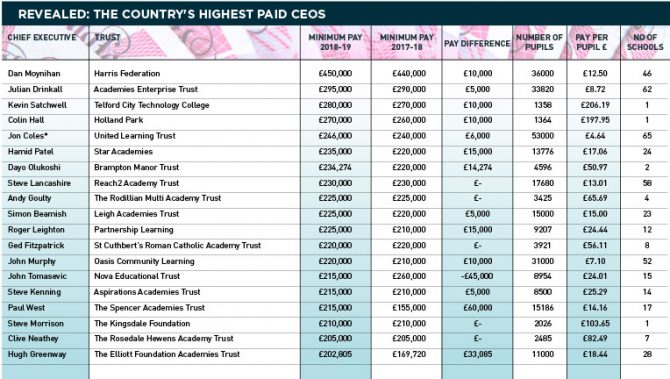

Who’s who in the best-paid bosses

Sir Dan Moynihan, chief executive of the Harris Federation, tops the tables again after a £10,000 rise took his pay to at least £450,000 (see table below).

Second is Julian Drinkall, chief executive of Academies Enterprise Trust, whose total pay rose to at least £295,000, up from £290,000 in 2017-18.

The trust said Drinkall has waived any increase to his £264,000 salary since joining in 2016. The rise is because he received a larger bonus this year of £31,000, compared to £26,000 last year, as “all major indicators relating to educational performance, financial health and professionalising governance” were “positive in the reporting year”.

However, it was announced in November 2018, during the reporting year for last year’s accounts, that the trust was to give up two more academies, which were rated ‘inadequate’.

Regarding his pay, the trust also highlighted that Drinkall had waived any pension contributions.

Leaders embarrassed by the pay of some in the sector

Sir Jon Coles, who runs the country’s largest trust, United Learning, saw his pay rise by £6,000, but the trust said it had reduced its pension contributions by the same amount.

Five of the bosses in our top earners also run fewer than five schools – three of them run just one school (including the third and fourth highest paid).

Trusts dropping out of the most highly paid table include Silver Birch, which closed, and Transforming Lives Educational Trust, which has not yet published accounts.

Ark academy trust, which runs 37 schools, said it has this year taken national insurance payments out of chief executive Lucy Heller’s salary – meaning it shows up as £191,017, rather than the £236,601 in last year’s analysis.

The largest pay rise, as revealed by Schools Week in January, was for Paul West, chief executive of the Spencer Academies Trust, which had 17 schools last year. His pay rose from at least £155,000 to £215,000 last year. The trust previously said this was down to “organisational growth and complexity” and meeting “educational and financial targets”.

Emma Knights, chief executive of the National Governance Association, wrote last month that trust leaders promoting ethical leadership are “embarrassed by the pay of some in the sector”.

While, according to Knights, it is a “small fraction of MATs involved in astronomical pay, the coverage tarnishes all who lead MATs. It is not helping academies in the PR battles, playing into the ‘privatisation’ critique.”

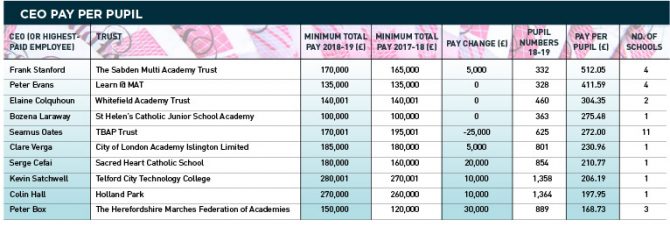

Per-pupil: Best-paid gets 110 times more than lowest

The analysis also found a huge disparity in pay according to pupil numbers – with the highest paid CEO earning 110 times more per pupil than the lowest paid.

However, a like-for-like comparison may be problematic as the highest earners in this category often oversee special academies or alternative provision, which tend to have far fewer pupils.

Frank Stanford, chief executive officer of the Sabden Multi Academy Trust in East Sussex, was the highest paid per pupil for the second year in a row (see table below).

His minimum pay of £170,000 worked out at £512 per pupil. The trust runs three special educational needs schools and an alternative provision school.

The trust did not respond to request for comment.

In comparison, Coles of United Learning was paid £246,000 for 53,000 pupils – equating to £4.64 per pupil.

Elaine Colquhoun, executive principal of the Whitefield Academy Trust, which oversees two special schools, cautioned that the per-pupil measure doesn’t “judge the complexity of the job” and may not be appropriate when assessing trusts with special schools.

The leader earned a minimum of £140,001, working out at £304 per pupil.

She said: “Our pupils all have special educational needs and encompass some of the broadest range of needs in the country – this means, for example, that one of our schools actually operates internally as three separate schools: primary, secondary, and one for children and young people with profound and multiple learning disabilities and related health issues.”

Colquhoun added the government had examined its pay structures and found them “reasonable in the circumstances”.

Elsewhere, Serge Cefai, headteacher of the Sacred Heart Catholic School, in south-east London, earned £211 per pupil. His remuneration rose by £20,000 to £180,000 last year, according to annual accounts.

This was driven by a bonus of at least £35,000 – up from £15,000 in the previous year. His salary has remained the same on at least £145,000. The school, rated ‘outstanding’ since 2012, said two years of bonuses were paid in the year, which was an “unusual occurrence and approved by governors”.

The school added that the head has opted out of the pension scheme to save “tens of thousands of pounds” and is now on phased retirement, so has a reduced salary.

Per-pupil benchmarks would mean more proportionate conversation and less hysteria

Leora Cruddas, chief executive of the Confederation of School Trusts, said she is in talks with the government over a more “sophisticated” approach to monitoring and benchmarking pay, based on the per-pupil metric.

She wants the government to machine read all accounts and produce a “simple” graph mapping the pay of accounting officers compared to pupil numbers, with a regression line and a tolerance threshold set either side.

She said this would show up the trusts that paying the larger salaries despite having just one school, and lead to a more “proportionate conversation and less hysteria”, rather than using the “blunt threshold” of £150,000.

She added CST is “fully committed to an evidence-based process for setting executive pay and to the vigilant observation of financial probity, the ethos of public service, public sector values and the principles of public life”.

It’s not just academy bosses getting rises

Accounts for Haringey Council show Tony Hartney, listed as chief executive of the local authority-maintained Gladesmore Community and Crowland schools, got a 16 per cent rise.

His pay rose from £177,718 in 2017-18 up to £205,622 last year, which would make him the 19th highest-paid CEO in the country.

The school teachers’ pay and conditions document states leaders’ salaries can only be raised 25 per cent above the maximum pay range in “exceptional circumstances”.

The council said Hartney was asked to take over as head of a neighbouring large primary school on an interim basis, so his salary was recalculated for the two years up to 2019 in accordance with pay rules. The arrangement has since concluded.

Elsewhere, the average principal salary for all further education colleges in 2017-18 was £136,000, according to an analysis by our sister title FE Week. For the trusts we looked at, the average was £148,000.

This average is similar to the pay of the best-paid education union leader, Paul Whiteman of NAHT, whose salary and benefits came to £147,158. Based on the most recent accounts available, the average pay (not including pension contributions) across the four unions’ five general secretaries was £122,000.

Academies compare favourably to other sectors …

An analysis by trade publication Inside Housing found the country’s largest housing associations were paid on average £174,896 in 2017-18.

Meanwhile, according to the Health Service Journal, there were 15 NHS trust CEOs paid more than £250,000 in 2017-18, compared to just four in the academy sector.

The NGA last year called for the government to introduce a system similar to NHS trusts where those wishing to award pay of more than £150,000 per year have to get ministerial approval.

Sam Henson, director of policy and information at the NGA, said the department is now looking to other sectors to explore how they can “get the message across” on pay.

However this analysis just looks at the highest-paid employee – many larger trusts now have growing teams of central staff paid over £150,000.

For instance, the 46-school Harris Federation has 31 employees paid over £100,000. The cost of their salaries last year was £4.83 million (on average £156,000) up from £4.74 million in 2017-18 (£153,000).

… But there’s an emerging gender gap

Of the 30 best-paid trusts, just five were led by women. The average pay for a male CEO among these trusts was £232,000. Among the five female CEOs it was £196,000.

However, this isn’t just a chief executive issue. There is also a gender pay gap at headteacher level. According to the 2018 school workforce census, male headteachers were paid on average £75,492 and women heads got £67,364.

It’s also not just in education. An analysis by Inside Housing found women chief executives of housing associations were paid £165,630 in 2018-19, 2.21 per cent lower than the £178,505 male chief executives took home.

Meanwhile the Health Service Journal found women health trust bosses were paid around £176,000 compared to £183,000 for their male counterparts.

A DfE spokesperson added: “It is essential that we have the best people to lead our schools if we are to raise standards, but academy trust salaries should be justifiable and reflect the individual responsibility – particularly in cases of significant increases. We will be making further challenges in the coming months.”

*A note on the method…

Pay refers to total remuneration (not including pension) as shown in the academy trust’s accounts, which can include things like bonuses and severance pay. It’s often presented as a salary bracket so we use the minimum pay level (unless we know the actual amount).

For the per-pupil stats, we use the total number of pupils on roll as published in accounts. If this figure wasn’t in accounts then we’ve used census figures or information from the trust’s website.

Your thoughts