“Not many staff feel able to do it, nor continue in [the] role for long,” Stephen Ellis, former head of the North Birmingham SENCos group, told MPs at their ‘Solving the SEND crisis’ inquiry.

He revealed three-quarters of SENCos in his area had “changed over a two-year period”, adding: “Morale is low. Turnover is high. Less and less time [is] given to SENCos due to funding cuts.”

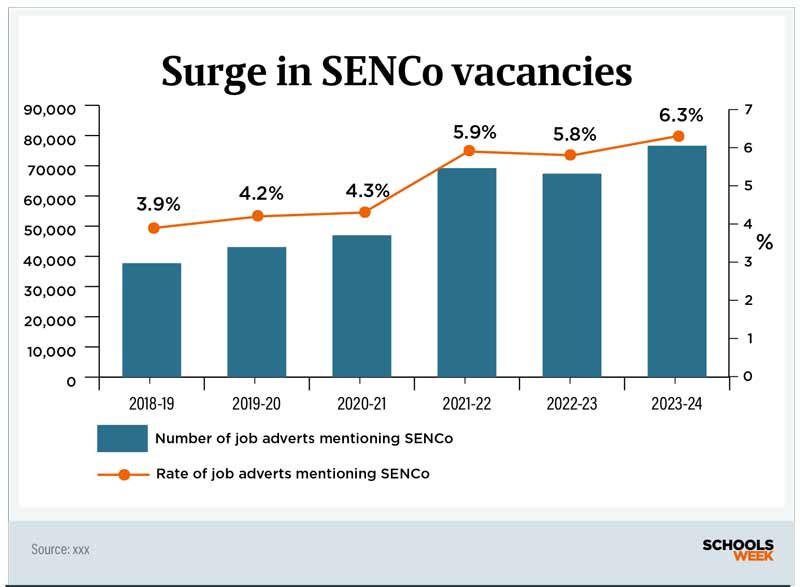

The number of teaching vacancies mentioning ‘SENCo’ or related terms soared from 37,737 in 2018-19 to 76,633 in 2023-24, SchoolDash analysis commissioned by Schools Week shows.

Vacancies averaged around 3,100 a month in 2019. This year it was more than 7,000.

The rise has also outstripped a wider surge in school workforce vacancies. SchoolDash found the proportion of vacancies mentioning ‘SENCo’ had risen from four per cent in 2019 to six per cent last year.

Every school is legally required to have a designated SENCo. But Abigail Hawkins, a former SENCo who runs support group Sensible SENCo, said some are waiting “18 months to get hold of somebody” to fill vacancies.

While many issues with the job are longstanding, experts fear they may now be exacerbated by reforms to make mainstream schools more inclusive.

SENCos will be “central to the success of any government plans to expand SEND provision within mainstream schools”, said Margaret Mulholland, SEND and inclusion specialist at leaders’ union ASCL. “But these roles have to be sustainable”.

In a submission to MPs, SENCo Kate Worrall added: “If you want to start improving the outcomes of children with SEND then you need to start with SENCos – they are the grassroots and they are leaving the profession in droves because they are overworked, undervalued and isolated”.

‘Overwhelmed by admin’

“Having sufficient time for the role is something SENCos say is the biggest issue,” said Michael Surr, head of education at SEND charity NASEN.

More than half of SENCos reported having teaching responsibilities on top of their role, according to the landmark 2018 SENCo Workload survey by NASEN, education union NEU and Bath Spa University.

The report called for different levels of protected time for SENCos based on their school type. Those in an average-sized primary should get at least 1.5 days for the role, with three to four days for those in a secondary.

But by 2020, only around two thirds of schools had met these recommended thresholds.

Dr Helen Curran, who co-authored the Bath Spa reports, said the “hope” of giving staff protected time “has largely not materialised”.

A 2023 poll of nearly 550 SENCos by Sensible SENCo found 17 per cent were given half a day or less per week to fulfil their duties.

SENCos are instead “increasingly overwhelmed by operational demands, often without sufficient time to fulfil even the core requirements of their role,” said Curran.

One primary school SENCo, who wanted to remain anonymous, told Schools Week she is “really struggling. I’m marking 90 plus books a day on top of my SENCo role. I end up doing SEN work during my PPA time, so I’m doing all my planning and marking at home.”

She is worried that this leaves children waiting longer for assessments and has approached her head to resign “a couple of times already”.

In March, Teacher Tapp asked nearly 400 SENCos if they expected to be in their role next academic year. One in 10 said no. Another 14 per cent said they were likely to be but would “prefer not to be”.

According to a survey of 358 SENCos by Twinkl last year, those looking to leave overwhelmingly cited workload – and the large admin burden – alongside lack of support and bureaucracy.

One said: “My average working week is now 60 hours Monday to Friday, plus eight at weekends. You suddenly end up realising you’ve spent more time with – and fighting for – other people’s kids at the expense of your own.”

Budget pressures force ‘multiple hats’

SEND recruitment expert Olivia Sheppard said ever-tightening budgets mean the role is increasingly “evolving into one wearing multiple hats”.

She knows of one school trying to hire a SENCo who will also be a SEN teacher and assistant head.

“But there’s only so long you can do it before you completely burn out,” she added.

In a recent NEU ‘state of education’ poll, two-thirds of the 625 SENCos surveyed said their workload was unmanageable.

The number of children getting SEN support rose to 1.6 million last year. Meanwhile, the number of pupils with an education, health and care plan (EHCP) has soared from 345,000 in 2019 to 576,000 in 2024 – 10 more EHCPs per school on average.

“Phone calls, meetings, paperwork, liaising with external specialists – it takes days to gather information required for an EHCP,” said Hannah Moloney, a SENCo of 14 years.

She helped spearhead the Bath Spa survey in 2018 after working in a school where she calculated her SENCo time equated to just 12 minutes per year for every child on the SEN register.

“There’s a huge disparity between what you need to do the job and the time you get,” she added. “And now workload is increasing – but time is not, meaning it’s actually a reduction in time for SENCos. It’s a perfect storm for workload.”

The fight for assessment

The government is considering reforms to the EHCP system which could see them “narrowed”. One idea is plans would only be issued for pupils attending special schools.

One SENCo told Schools Week she has children who have been waiting since October 2023 for their final plan – more than 80 weeks.

“They’re never going to get that time back,” she said. “We haven’t got time to hang around. It’s just not fair.”

When children are given EHCPs, many also include requirements schools simply cannot provide.

Former SENCo Robin Jones-Ford highlighted an EHCP that said a secondary school pupil must have “an individual workstation in every classroom”.

“That might possibly work in primary, but there’s no way on God’s earth that’s going to work in secondary. But it states it in the EHCP, so the school is legally required to provide that.”

SENCo Kerry Bircher said one child at her school is required to have “special time… basically where it’s complete one-to-one, no interruptions between a trusted adult and that child.”

But funding the school gets for that role does not cover the cost.

SENCos said these issues are exacerbated by a lack of external specialists, such as occupational and speech and language therapists.

It sticks in your throat to see SEND funding being pulled out to paper over the other cracks

Meanwhile, many are forced to watch as much-needed funding they have fought hard to source for pupils with SEND is instead spent on patching up holes in their school’s budget.

Jones-Ford said a lack of ring-fenced funding made his role feel “impossible”. As a former head, he understands “how difficult it is to balance a budget” but it “sticks in your throat” to see SEND funding being “pulled out to paper over the other cracks”.

‘I’m banging on the door’

The SEND code of practice recommends SENCos are on the senior leadership team. But a 2022 Teacher Tapp survey found just 43 per cent of secondary SENCos were, compared to nearly three-quarters in primaries.

One SENCo told Schools Week that because she is not on the SLT, she feels children with SEND are “out of sight, out of mind” when decisions are made.

“I’m standing there banging on the door, saying, ‘what are we doing for this child?’ They get lost in the process.”

Bircher said this should be a requirement. “If you’re not on SLT, then I think that speaks volumes in the priority that your school gives to inclusion.”

Salaries also vary wildly. Slightly fewer than one in five SENCos who took part in the NEU survey were in the leadership pay range, with just over half in the upper pay range. Most of the rest were in the main pay range.

The 2020 National SENCo Workforce Survey found 70 per cent of SENCos were receiving extra pay for the role – which could be a SEN allowance or TLR.

Responding to the NEU’s recent ‘state of education’ survey, SENCos aired frustrations over pay inequity, adding it was “very unhelpful” that schools are “given autonomy over how they pay” them.

Ellis, in his submission to MPs, said someone can now earn “as much in local supermarkets and Amazon as they can earn being specially trained and experienced SEND staff”.

Moloney, highlighting research suggesting 90 per cent of SENCos are women, said “people underestimate the level of skill and knowledge required”.

What needs to change?

Many who took part in the NEU survey suggested protecting SENCo time is key to solving problems. The SEND code of practice only states schools “should ensure” SENCos have “sufficient time” to do their job.

Some said having a SENCo on the senior leadership team should be statutory – and they should be paid on the leadership scale.

SENCos “should be senior, strategic leaders in every school”, said Bart Shaw, operational lead of the Whole Education SEND School Improvement scheme which has worked with 1,000 schools nationally.

But many staff also want “more of a whole-school approach to SEND”.

Katherine Walsh, director of inclusion at the River Learning Trust, said: “We need all teachers and leaders thinking about experience and outcomes for children with SEND. The SENCo should be a strategic leader to make sure everyone is working together with collective accountability.”

Ginny Bootman, an author and SENCo of 20 years, said there has been “a push for the need for assistant SENCos [so] it doesn’t all fall to one person. Division of the role” – with one SENCo responsible for admin and another in the classroom – “could also be helpful”.

But Moloney said the current “crisis is an opportunity for significant change. I think the next 10 years will be transformational – it’s such a massive job, it can’t just be one person.”

She also believes SENCos need to be better skilled in “screening and identifying needs at a basic level”.

“We haven’t got other people to rely on [to do this] anymore. So we don’t know what children’s needs are, don’t know enough about the complexity of supporting these children nor how curricula can adapt. This means we lack awareness and understanding for how to fund and deliver education because we have a huge knowledge gap.”

Amelie Thompson, assistant director of education (SEND) at the Greenshaw Learning Trust, called for a relaunch of a study similar to the Bath Spa Workload Survey, adding that inclusion reforms meant it was “key we fully understand how the role of SENCO is positioned and enabled as a leadership role”.

Surr suggested a “SENCo register” could form part of the annual school workforce census to better understand the job.

‘It’s the best role – we need to enable that’

Experts have welcomed the new national professional qualification for SENCos, a leadership course that is now statutory.

But Mulholland called for an expansion “to allow schools to train more than one SEN leader at a time” to allow for succession and strategic planning.

Thompson said the oversubscribed NPQ showed there was a “real desire to understand how to build inclusive systems and how to enable the SENCo in their role”.

She added groups of schools can help “centralise SEND efforts” to build an “understanding there’s a responsibility we all share. It’s about making this built into structures and strategies, not a bolt on”.

Walsh said trusts can also help reduce the administrative burden. For instance, River Learning Trust has worked with Oxfordshire to streamline EHCP consultations. This has enabled its schools to prioritise responses based on parental preference or nearest school – rather than up to seven SENCos responding for the same pupil.

“Each prioritised consultation gives our SENCos two hours back,” she added. Another example was how SENCos can share solutions for children with similar needs.

A report by the National Foundation for Educational Research found the introduction of trust-level SEND leaders had played a “significant role” in helping SENCos deal with challenges, and being part of a trust helped “alleviate the isolation”.

Walsh added SENCo is the “best role in school – it’s a really innovative one and we need to enable people to see it that way”.

River Learning Trust is moving the role away from admin and to an “expert teaching and learning role,” she said. “If SENCos are supporting teachers – they need to be working alongside them”.

Management tries to protect half of SENCo time for being in class, doing learning walks or overseeing interventions.

“We aspire for all of our new heads to have done the SENCo role,” Walsh said. Thirty-nine per cent of children have SEND at some point – we need all leaders to understand this proportion of their school population. We can’t have a system for children, and a system for children with SEND.”

If schools were open to unable parents to work as volunteers, many of these parents cannot have a normal day job because they need to be available for their children.

Send parents have to fight so much and educate themselves to support their children. I would 100% volunteer and I’m sure that I would be a great asset. Then if successful, school’s should open the doors and employ them. It would be a great support for school’s.

If SENCOs are leaving in droves why are there no jobs? A very keen SENCO here covering a maternity post looking for a permanent position and there are none!