The dwindling number of nurses in schools means junior staff are forced to undertake complex medical procedures on vulnerable pupils.

The situation is so bad that one prominent special school trust may be forced to take legal action against its local health board.

And new data reveals support staff feel pressurised into providing care without suitable training amid warnings of “disastrous consequences”.

Schools Week investigates…

School nurses disappear

The Eden Academy Trust used to have an NHS school nurse for each of its three special schools in Hillingdon. Now it has two nurses covering four schools, with two new schools on the way.

The schools have dozens of children with epilepsy, or who require respiratory management or enteral feeding. But, instead of properly funding clinical support, the local NHS body wants school staff to take on more and more medical roles.

“Over the last five years, there has been more emphasis on what can we do,” says Carley Holliman, deputy CEO of the Eden Academy Trust. “What can our teaching assistants do? Can we start recruiting therapy assistants or healthcare assistants?”

Last summer, a school nurse retired and was not replaced.

The local NHS body, the North West London Integrated Care Board (ICB), asked the academy trust’s leaders to perform annual “competency” checks to ensure that school staff can correctly perform clinical procedures – checks the trust’s leaders feel they lack the expertise to carry out.

‘Significant risk’

The trust’s CEO Susan Douglas wrote to the ICB in early March, urging it to replace the retired nurse and assess and meet the healthcare needs of the 170 pupils at the two schools opening next January – something it has not yet done.

“The lack of these NHS services is creating significant risk to the health and life of these children and an unnecessary burden on NHS acute services as a result of school staff contacting the NHS ambulance services on an increased basis,” Douglas wrote.

Her letter warned that the trust was taking legal advice. After a long delay, the trust finally received a response from the ICB’s chief nursing officer saying it was reviewing its services, but providing no timescale.

The trust’s lawyers have now written to the ICB. A judicial review may be the next step.

Nurse numbers fall

The problems facing the Eden Academy Trust are a microcosm of those faced by schools up and down the country, as cash-strapped NHS bodies try and shift responsibilities – and their financial costs – elsewhere.

NHS data for England shows the number of full-time equivalent school nurses has fallen from 3,000 in 2010 to around 2,000 now.

The National Association of Headteachers (NAHT) annual conference in May debated a motion highlighting the problem.

Proposed by Marijke Miles of the NAHT’s practice committee, the motion warned that Department for Education guidance is being misinterpreted and used to pressure schools into providing medical care.

According to Miles: “Clinicians up and down the land are quoting it as a requirement for schools to undertake clinical procedures, including ones that are quite invasive, when that is not what the guidance actually says.”

The NHS is meant to work with schools to ensure that needs are met but often delegates its roles to school staff instead, Miles adds.

Burden falling on lowest paid

And that burden is increasingly falling on the lowest-paid workers.

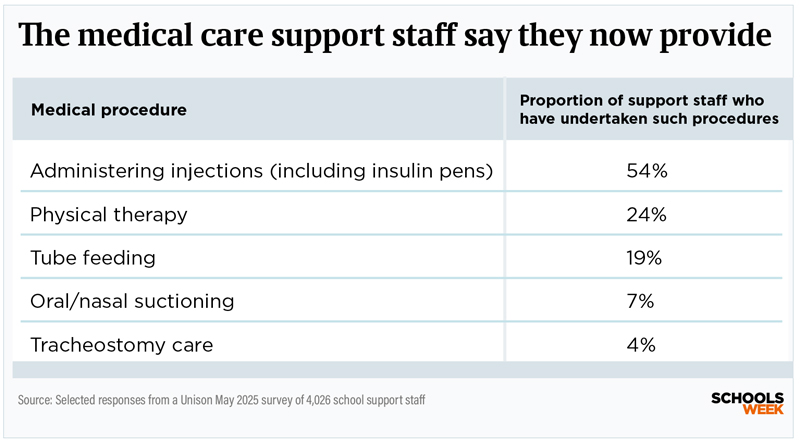

More than two in five support staff say they have no option but to give injections and administer prescribed medication to pupils alongside their other duties, a Unison union survey of 4,000 workers found.

The survey, conducted in April, was seen exclusively by Schools Week.

The clinical tasks and medical procedures undertaken by support staff included administering oxygen, changing feeding tubes, oral suctioning and dealing with seizures.

“Administering essential medical care in schools should be the responsibility of trained health professionals, not low-paid support staff who feel pressured to do it because there is no one else,” says Mike Short, Unison’s head of education.

“Teaching assistants, administrators and catering staff, who are already picking up the slack elsewhere in schools, should not be forced to act as nurses, physios and occupational therapists.”

But two-thirds of respondents, mostly from primary and secondary schools, said the health support expected of them had increased since the pandemic. Scores of support staff said they had been involved in tracheostomy care or intermittent catheterisation.

“I think it’s intensifying, and I think it’s going to intensify further with the increasing inclusion into mainstream schools,” Miles says, referring to government plans for more children with additional needs to be educated in mainstream provision.

‘Accident waiting to happen’

Any delegation of tasks from healthcare providers should incorporate risk assessments and ensure the staff member is trained, insured and willing to perform the role and that it is in their job description, Miles adds.

“[But] we are encountering people who are trying to ask schools and school staff to basically watch videos online and then go off and do something that gets really quite invasive.”

The Unison survey found just four in 10 staff polled were confident they could refuse tasks they were uncomfortable with.

Fewer than two-thirds felt they had received sufficient training for the healthcare tasks they undertake, mostly because of lack of time or funding. Many had only done a one-day first aid course.

Fear of mistakes

Fewer than half of surveyed support staff had their training signed off by a healthcare professional. Training was often provided by other support staff or family members of the pupil.

One respondent said they “cannot remember the last time we had a school nurse in”. Others said that, despite the services being vital, most contact was “via email” and it can be “months before we get a response” for help.

Nearly two-thirds cited the fear of making a mistake, with most concerned about being blamed should something go wrong.

“At one point I had an unconscious student, a hypo student, a head injury and a nosebleed that I was expected to deal with,” one support staff worker, who did not want to be named, said. “All at the same time.”

Another said: “I learned how to give insulin injections from another teaching assistant. It feels like an accident waiting to happen, even though we are all very careful and professional about our children’s needs.”

Unison’s Short adds that any accident could have “disastrous consequences”.

Calls for new laws

Support staff said leaders relied on terms such as “other duties” or “first aid responsibilities” in job descriptions to justify staff carrying out medical procedures.

But government guidance states that “first aid at work does not include giving tablets or medicine”, apart from aspirin on occasions.

“This issue has been hidden in plain sight for about 10 years,” Emma Smith, a consultant and expert in the law around medical practice, says.

Among the triggers for this shift, she pinpoints the transfer of public health school nursing services from the NHS to councils in 2013 without a nationally agreed service delivery model for clinical nursing services in schools.

“Because we’ve had this 10-year period of misunderstanding and misapplication of the law, we have this service delivery model that has become embedded, but it actually is divergent from the legal framework,” Smith adds.

She also says the Department for Education’s statutory guidance on supporting pupils with medical conditions at school, first published in 2014, contains “several missteps” around the delegation of NHS healthcare activity to schools.

“The hidden cost to special schools and the absence of health funding is criminal that it’s allowed to happen, and it’s not something that the DfE seem to acknowledge at all,” says Warren Carratt, chief executive of Nexus Multi Academy Trust.

“Instead, we’re inflicted with real-terms funding cuts year after year.”

‘No full-time nurses’

His trust pays for staff medical training from already-stretched budgets when the NHS does not have the capacity to provide it.

“Most of our special schools don’t have a school nurse in full time, despite the fact that we support children with incredibly complex needs.

“I understand that the system’s stretched. It can explain it, but it doesn’t excuse it.”

His teaching assistants regularly have to perform tracheostomy care, plus “blue light” occasions when an ambulance has to be called because a child suffers an acute health incident.

“With these pupils, two or three times a day you are responsible for a child breathing. And that is just a very stressful responsibility that, technically, has got nothing to do with teaching and learning.”

Kids miss school over missing services

One of the Eden Academy Trust’s Hillingdon schools, Sunshine House, has children with very complex needs. The school has had to hire four healthcare workers from its own budget.

Andrew Sanders, executive head at Sunshine House, says classroom staff can feel vulnerable when, as often happens, there is no nurse onsite.

“If they are not sure about how a child presents – so they have a seizure or something like that – they will try and phone one of the nurses, but they can’t even always get in touch with them,” he says.

The ICB has advised the school to call 999 or ask the parents to pick the child up. “That either means they have got to go to hospital to be checked over and a member of staff has got to go with them, or parents have got to leave work to take them to the GP and so on.”

Pupils ‘missing school’

These issues mean a “significant number of pupils are missing school because the NHS services are not in place,” says Smith. “Which is an absolute travesty.”

One in 10 support staff said pupils were absent from their school because appropriate health services were not in place, the Unison survey found, rising to one in five at secondary.

Smith gives an example of children who receive continuing care packages at home that don’t extend to school, which can leave school staff to carry out that care activity.

“And if schools say they can’t, or they’re unwilling to do that, then it means that children can’t go to school until the stalemate has been addressed.”

This very issue has arisen at Sunshine House. “We’ve drawn the line at deep suctioning,” says executive head Sanders.

“We were asked to do deep suctioning, but we’ve said that we won’t carry out those procedures.

“And there was one pupil who was supposed to be coming with a carer, but then the NHS withdrew that carer, and then we said that the child wouldn’t be able to attend school because we were not qualified to carry out those deep suctioning procedures.”

Playing hardball pays dividends

The North West London ICB responded by saying it would provide a carer, but funded from the child’s home care budget. As a result, the parents have decided to home-school their child instead.

Elsewhere, playing hardball has paid dividends. When Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire and Berkshire West ICB wanted Frank Wise School in Banbury to provide deep suction for a child with respiratory care needs, the school refused.

“We made it clear that that was a task that should be performed by a clinician because it required the interpretation of clinical information, and that’s a line we won’t cross,” says headteacher Simon Knight.

“So, if there’s any element of clinical information needing to be interpreted, we won’t do that.”

The NHS agreed to fund a package of care that allowed the child to remain in school full time – and to go on residential trips.

“That’s a real win,” says Knight, “because it means this child is fully included in the school community. But it required us to be really clear about what was reasonable and what was unreasonable in relation to delegation.”

The Department for Education referred Schools Week to the Department for Health and Social Care, which did not respond to a request for comment.

‘We need new system’

North West London ICB would only say it was “working” with Eden Academy Trust to “address the issues that have been raised”.

The financial constraints on schools and the NHS are not going away anytime soon, so tensions are likely to continue.

ICBs have been told they must cut their running costs by 50 per cent by October. Eden, in its legal letter, said it had been told that no assessment of health needs at its new schools had taken place because of a “wider review of all school healthcare across the ICB”.

But Unison is now calling for the government to review the legal basis for delegation of clinical tasks from the NHS into schools.

One solution could be an NHS-commissioned, needs-led clinical school nursing service for schools, alongside a public health nursing service commissioned by local authorities, the union added.

Smith wants to see a national delivery model for clinical nursing services in education settings. “And we also need compliance,” she says.

“We need to ensure that everybody understands the legal framework, and that everybody is implementing the legal framework as well. And that’s at every level.”

“We are educators,” Eden’s Holliman adds. “We’re there to look after the education. Medical needs need to be dealt with by medical teams.”

Very poingnant portrayal of the reality in Special Schools – tragedy waiting to happen.

It is good to see how this issue has been so clearly described here. The risks in having to carry out invasive procedures are significant for children and staff and there is no acknowledgment anywhere that it needs medically trained staff to carry these out safely. The failure of the healthcare system and healthcare professionals to recognise their duty of care in schools is a potential disaster for thousands of children. The ‘training’ offered to school staff to carry out these procedures would be seen to be laughable if it didn’t involve potentially causing harm to children. I will never forget the advice given when being told we have to catheterise a child. “If it bleeds a little bit, call Mum. If it bleeds a lot, call an ambulance.”

Imagine this: Band 7 nurses, earning £23–£26.50 an hour, rightly refuse to carry out a medical procedure in hospital because it’s too complex and needs senior clinical oversight. But when that same child returns to school, it’s a £12-an-hour Learning Support Assistant expected to carry out that same procedure — alone, with little medical training, no supervision, no specialist union, and full personal liability.

This is not just unfair. It’s dangerous. And it speaks volumes about how little value we place on some of the most critical roles in education and care.