It seems Avnee Morjaria’s modus operandi is cutting to the chase.

She’s responsible for all public service policy at the IPPR, a think tank known to be influential in Labour policy making.

It’s a stressful job, she says, but perhaps not as stressful as the one Rachel Reeves’ has (we meet on the day of the chancellor’s spring funding statement).

The venue is a quiet cafe along Millbank, a pleasant suntrap while the metaphorical clouds engulf Westminster less than a mile away.

“I think the education sector is probably in the worst place that it has been since, well, for decades, in terms of the amount of resources that it’s got committed,” Morjaria says.

“We shouldn’t be [having to] find cuts in the schools system. And if you want to find efficiency, you need to do reform. That takes time – and is not going to deliver you the savings you need for this kind of fiscal statement anyway.”

Time in teaching

Morjaria was born in Leicester, to parents who had been expelled from Uganda under Idi Amin’s dictatorship.

She attended what she described as a ‘coasting’ school. “It wasn’t the worst school, but it wasn’t the best school either.”

She said she was “a bit too bright for my own good.” I was bored and easily switched off, that didn’t result in anything terrible. Some bunking off… [but] I got the syllabuses and books and I taught myself and that worked for me in terms of the grades that I got, but I guess not the best way to deal with the school environment.”

Morjaria’s time in college studying A-levels sparked her interest in teaching.

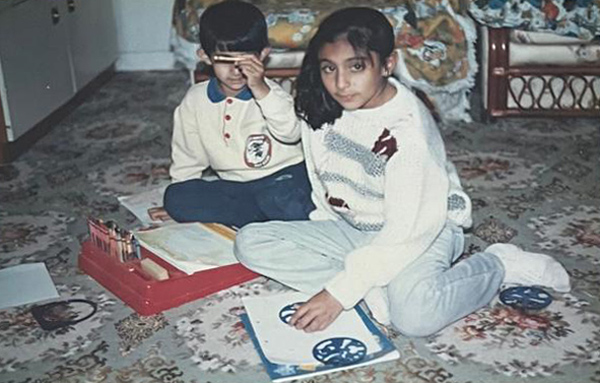

Young Avnee

“The staff were pretty absent,” she says. “People off, on long-term sick leave, and continuous supply teaching across a couple of different subjects.

“When I looked across at more affluent members of my family and the schooling they were getting and paying for, I understood how transformational good education can be.

“I really wanted to, without sounding cheesy, make a difference.”

Morjaria began her career teaching maths after studying the subject at the University of Warwick. It was a utilitarian choice – she tells me she would have loved to have read politics.

“As a teenager I didn’t really understand what my options were and where they would take me,” she says. “I enjoyed maths, I had a good maths teacher, and she was the one who was consistently there.”

‘I absolutely loved pastoral care’

Morjaria enjoyed teaching “and the banter with the teenagers”, but realised the subject she picked to teach was “absolutely wrong. I hated the subject content, and while I loved the job, I hated that element of it.”

She worked at Stoke Park and Lyng Hall schools in Coventry, teaching largely white working class children, many deprived and some who lived in caravans.

Morjaria entered senior leadership at Lister school and Elmgreen school in south London. She was responsible for pastoral care, “which I absolutely loved”, and supporting young teachers.

Lister school was rated ‘satisfactory’ in 2012, but improved to ‘good’ with ‘outstanding’ behaviour.

“We did a thing called Lister character to work together with the pupils to define what that meant and what it meant to be a good pupil,” she says.

What helped was consistent systems and routines. “When it came to crunch time teachers were supported where things didn’t work out.”

The Ofsted call

Morjaria also inspected while she was a senior leader, a job she describes as “one of the most difficult” she has ever done.

“The way that inspections were conducted, it was super high stakes for a school,” she says.

“A one-word judgment against a few categories could change the outlook for the local community. It could change the careers of the senior leaders there.

“It put a lot of pressure on the teachers, and that made the responsibility of the job itself super high stakes, because you wanted to make sure you got it right.

“[But] you can’t really see what a school is like in two days. There’s a lot for you to understand and to take in and you can’t do that in two days.

“There were a lot of moments where I felt very sad leaving inspections. Did I ever feel: ‘Oh, that’s brilliant. I had a great day’? Not really.

“There were the kind of isolated moments where there were schools that got a grade above what they expected, and they were pretty elated with that. Most of the time when schools are going to be good or outstanding, they already know.”

Despite this, does she welcome the reforms to Ofsted?

“I’m not wholeheartedly sold on the new report cards, but on the other hand, I don’t know what the right answer is. I think that they’ve got an incredibly tough job in trying to find that answer and do the job that they need to do with the responsibilities that they’ve got to parents and students.”

Education strategy

In 2016, Morjaria moved into the Department for Education to work as an assistant director on various strategy roles, including heading up the education recovery, remote education, and the curriculum strategies during the pandemic years.

She was also part of the education recovery strategy which included the national tutoring programme (NTP), with a focus on supporting disadvantaged pupils. Around 2.5 million courses were delivered under the NTP.

But now the scheme has ended, and funding has dried up, few leaders can afford to keep this support going.

“There was a time where Kevan Collins [the then Conservative government’s recovery commissioner] set out some proposals, and those were good ones,” Morjaria says.

“But they were never funded, and what we ended up with is the National Tutoring Programme, which really isn’t a sufficient response to what had happened.

“Schools don’t have the money for tutoring – they’ve barely got the money to hire teachers.

“If I was a senior leader now, would I prioritise tutoring in terms of my budget? No, I would prioritise things like attendance, employing teachers, and training teachers.”

But the biggest issue Morjaria identifies is mental health. She said the rise of related issues since the pandemic “were never dealt with or invested in”.

“We really should have thought about the overall impact of Covid, not just on kids’ attainment, but more broadly than that,” she says.

“I just don’t think that the DfE, which was responsible for intervening and supporting children after that disruptive period, ever really got to grips with that.”

Policy life

Before moving to the IPPR, Morjaria briefly spent time as a policy and strategy director at Oxford University Press. She enjoys the big-picture thinking that policy roles provide.

a sufficient response

She says: “I love thinking about the whole system, the policies within it, how to work together to make life better for people.

“When I was in actual government civil service-style roles, I got to do that with ministers. Here at IPPR, I get to do that, but also I get to be a little bit political about it, or I get to think about the politics as well as the policy. I’ve been super lucky.”

Morjaria is focusing on social mobility. “We’ve got some pieces out in education on how empowering the workforce could be the next thing that makes the big transformational change, and how great leadership could be that too.

“How do we change the narrative to one that talks about reducing inequality, a broader impact about making the difference on a larger scale to children’s lives?”

So, with her policy hat on, what’s her advice to education secretary Bridget Phillipson?

“My advice would be that children and young people are operating in a more complex environment than ever before, and schools will need to broaden their scope and offer to help children and young people to deal with this complexity,” she suggests.

“Labour shouldn’t be worried about this approach, both with the public and the sector, as everyone already knows that it is needed.”

Your thoughts