Trusts running almost 100 schools, chief executives paid over £500,000 and a litany of high-profile collapses weren’t really what Michael Gove envisaged for his “letting a thousand flowers bloom” academy reforms.

While there have been many notable successes, the journey from 2010 to today is one also stacked full of financial scandals, of trusts growing too quickly and of getting governance wrong.

But what if you could design a new system, based on the same principles, without having to drag everyone through those tough lessons?

That’s what Tasmania, an Australian island state thousands of miles from England, is now embarking on.

While it may have a fraction of the number of schools in England, the state government hopes creating “multi-school organisations” with joint executive leadership and aligned curriculum, teaching and operations will help it overturn entrenched low outcomes.

Many of the features will be similar to the English system. Ministers believe grouping schools will allow them to pool resources, reduce administration and improve teaching through collective expertise. Appointment of executive leaders will boost accountability, they say.

But unlike our academies, Tasmanian schools will not go through the complicated “academisation” process.

‘It isn’t hitting the mark’

Jo Palmer, Tasmania’s minister for education, told Schools Week reform was needed because, although things like phonics and its “lifting literacy” campaign have prompted some improvements, “we just are not seeing the outcomes that we want to see”.

Tasmania has a year 12 achievement rate of just 53.1 per cent, the worst of any Australian state. It means almost half of pupils do not complete the final year of their secondary education.

“We’ve never seen so much resourcing in the education space, but it just didn’t seem to quite be hitting the mark,” says Palmer.

A government-commissioned review concluded earlier this year there was “merit in trialling multi-school organisations in schools and communities that are interested in, and will be supported with, this approach”.

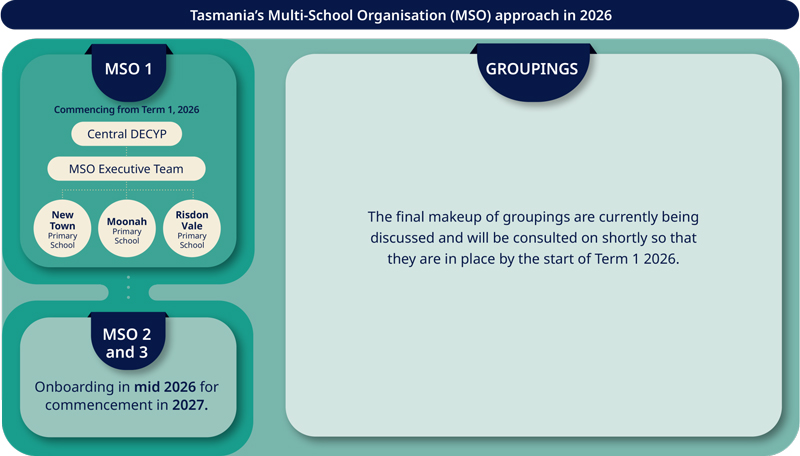

That trial will begin in January, with three primary schools in Tasmania’s capital, Hobart, forming “MSO1”. That organisation will expand throughout the five-year trial, and ministers plan to open two more MSOs in 2027.

Aim is for all schools in groups

Schools not yet in an MSO will be placed in less formal groupings from January, led by newly-recruited “executive leads”.

The government says these groupings will deliver “clearer reporting structures, create peer learning groups for educators, and provide greater accountability while preparing the foundations for the expansion of MSOs”.

“All of our other schools will be in their groupings, [and] will have already been on the journey,” says Palmer.

“They will have been watching how this plays out with our MSOs, and then, my hope is that we will see this transform and be implemented across the state.”

Education is devolved to state level in Australia, allowing Tasmania to proceed with the reforms without central government approval.

‘Increase the odds of school improvement’

Tasmania’s interest in England’s school system was piqued by a 2024 Grattan Institute report, which found that MATs in England and their equivalents in New York “increase the odds of school improvement”.

“Leading strong families of between 10 and 100 schools, these MSOs have a mandate to maintain high standards, and are accountable for doing so,” the report continued.

“Each has a clear blueprint for running an effective school, and the authority to enact this blueprint across multiple schools, including turning around schools that have under-performed for decades.”

The report concluded that trusts’ “Goldilocks” size helped, making them small enough to understand specific challenges, but big enough to “marshal the resources and expertise their schools need”.

Grattan commissioned Australian charity McKinnon to organise visits to UK trusts, including United Learning, Star Academies, Dixons and Delta.

The charity in turn hired Brits Will Bickford-Smith, a former DfE adviser, and Matt Hood, a trust chair who also set up England’s Oak National Academy, as advisers.

‘Kids in love with learning’

Visiting trusts over here, Palmer says she saw “kids in love with learning and teachers in love with teaching.

“And it’s almost as simple as that, isn’t it. If you’ve got those two things, you’ve actually got a robust and aspirational education system.”

One of the benefits of visiting England was the “fact that you are so many years down the road in this model”.

“What was incredible was the enormous generosity of the teachers and the leaders that we met, who were so open and honest about ‘look, this worked. This wasn’t great. If we did it again, we’d probably look at this’, warts and all.

“It was actually quite an emotional trip, because we came away thinking, wow, is there something that is happening in schools on the other side of the world that could actually make a real difference to a system here in Tasmania?”

No CEO pay freedoms

But the huge expansion of the academies system in England over the past 15 years has not been without its flaws.

Some trusts expanded far too quickly, affecting their ability to improve schools. And a lack of oversight in the early years of expansion led some high-profile chains to collapse following financial mismanagement.

England’s approach has involved creating separate legal entities and allowing trusts to deviate from established national pay and conditions for staff. This has often led to clashes with unions.

Perhaps reassuringly, Tasmania is not choosing to emulate those complicating aspects of academies. Although they will have their own executive leadership, new MSOs will not become new legal entitles, and they won’t deviate on pay and conditions.

Academy executive pay varies hugely and has been a controversial topic here. Tasmania will adopt a simpler approach, using existing pay scales for senior government employees.

Tasmania ‘intentionally rebuilding its system’

MSOs will be given autonomy, but the state is still deciding exactly what will be delegated to schools. The state will continue to set rules over things like safeguarding, will hold schools to account, and support priorities such as literacy and wellbeing.

Tasmania is also still deciding what governance structure the MSOs will have. Although schools have parent and teacher councils, they are currently directly run by the state.

Bickford-Smith, an adviser to the DfE between 2023 and 2024, said England’s trusts had “led the way” in tackling education issues, but the country “stumbled into the model and still lacks a clear vision for where the system is heading.

“Tasmania, by contrast, has taken the bold step of intentionally rebuilding its system through trialling MSOs – drawing on what has worked in England, and adapting the model for Tasmanian schools.”

He said this meant each MSO “starting small, embedding high standards, and scaling only at the pace that allows those standards to be maintained”.

Evaluation lessons

Another lesson learned from England’s journey is the importance of early evaluation, Palmer says.

“That was a little bit of feedback that we got from a number of people, is that they waited for a period of time, and then they went in and evaluated.

“And they said, ‘well, if we could have our time again, we would start that evaluation straight up’. So that’s one of the things where we’ve gone, okay, day one, the evaluation begins.”

Palmer says “everything that we’ve taken from your model is actually all about uncomplicating things.

“It’s actually very much about stripping out the complications that I think, as government, we have put into schools and saying, you know what, our teachers just want to teach. It’s what they want to do.

“And our school leaders and our principals, they want to be working on inspirational professional development and curriculum. And everything about this model is saying, you know what, that is your area of expertise.

“You go do that and let us manage some of the things that are not meant to be part of being a principal in a school or being a teacher in a school.”

Another criticism of the expansion of England’s model is that some trusts ended up with groups of schools that were geographically incoherent.

Minister impressed by ‘turnaround’ schools

Palmer thinks geography will “certainly be part of what schools we bring into MSOs…I think there’s some obvious advantages to that.

“But it won’t be the only thing that we’re looking at.”

She said she had been particularly impressed by so-called “turnaround schools” in England – those with entrenched failures taken on and improved by trusts.

Palmer was “blown away” by a visit to Lowry Academy in Manchester, she says. The school became famous under its previous name, Harrop Fold, when it featured on the Channel 4 documentary Educating Greater Manchester.

It was subsequently rated ‘inadequate’, closed and reopened as an academy under United Learning. Last year, its former headteacher Drew Povey was banned from teaching for failing to prevent off-rolling. It was rated ‘good’ in early 2024.

As they have been in England, union leaders are wary of Tasmania’s plans.

Union concerns

The Australian Education Union criticised Palmer for implementing the MSOs trial without consultation, while ignoring other recommendations in the government’s education review.

David Genford, AEU Tasmania president, said: “We need smaller class sizes, more time to prepare, and more in-school support for students. We’re bargaining for a new teachers’ agreement and we won’t be ignored again.

“It’s insulting that we have an education minister who has gotten distracted by a shiny new toy and has completely dropped the ball on fixing the crisis in schools.”

But Palmer is defiant.

“I think wherever there’s change, people become uncomfortable, and that’s okay. Sometimes it’s so much easier just to go, ‘oh, well, it is what it is’.

“But that’s not what we’re elected to do. When you’re in that situation where you’re well-resourced, you’ve got a hard-working workforce who are exceptional with what they do, but still you don’t have the educational outcomes, you have to look at the system.”

The state is now seeking the MSO system’s “founding CEO”. Their search is international, including in England.

“We are looking for a rock star educator. And we’re excited to see who may put their hand up and step up to this. It will be a very exciting position. You’ll be right at the forefront of shaping something pretty extraordinary.”

She points out Tasmania isn’t the only Australian state looking to England’s system for inspiration. Schools Week understands delegations from other areas have visited trusts including Ark, Trinity and Twyford.

“We know that there are eyes around Australia who are watching what happens in Tasmania. I don’t know. You might have some Aussies who want to come home, maybe, and take up a challenge?”

Changing the exam board to an easier one is what those MAT chains have done – that’s all they need to do to emulate their ‘success’. Good old fashioned gaming the system.