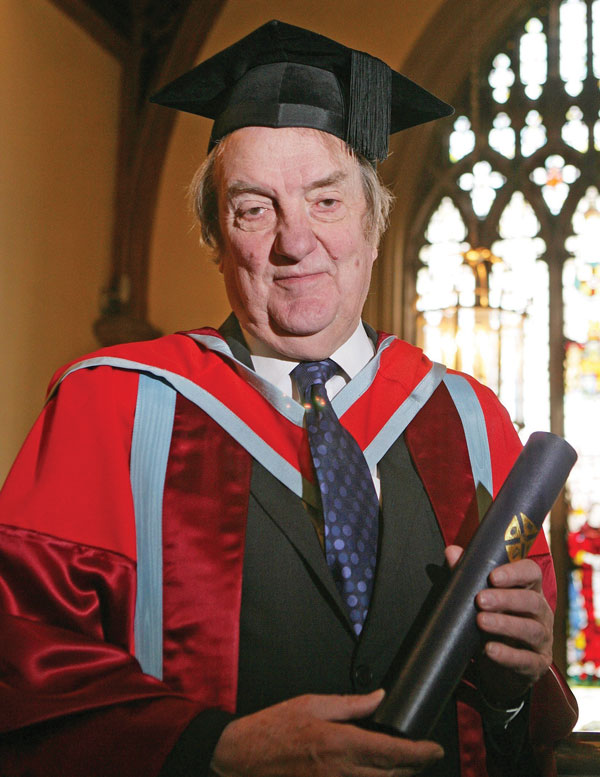

The longer you talk about a problem in education, the more likely you tend towards the solution “clone Tim Brighouse”. Yet the twice-retired 74-year-old seems to have enough energy to be in multiple places at once, even without genetic splicing.

In the week we meet he has spoken at two conferences, will soon attend a TeachMeet event where teachers share ideas, and when a passer-by invites him to another event he expresses concern that he already has two governor meetings that day but he’s hopeful it can still be squeezed in.

With a career in education spanning more than 50 years, Sir Tim is known for a plethora of things – saving London schools, saving Birmingham schools, arguing with the abrasive ex-Ofsted chief Chris Woodhead and, perhaps most extraordinarily, for suing then-education secretary John Patten after he claimed during a Conservative party conference that Brighouse was a “madman” who went around “frightening the children”.

There’s no doubt that Sir Tim comes across as eccentric. His voice booms with enthusiasm; his eyes are bright and warm; his gestures always exaggerated. But these features combine to infuse listeners with a belief that they are special and important, and that teaching is the best job in the world. He is, in a literal sense of the word, brilliant.

“I could take risks and know that the politicians wouldn’t try anything”

He is also well aware of his manner: “I think I was much more informal …even in more formal times… but if you’re informal you’re very quick to overcome perceived barriers. People begin to see who you are and what you say and what you do, and whether it’s genuine or it’s not genuine – I think that’s a help. I mean, it isn’t that I put it on, I am informal!”

Life didn’t begin so informally. In fact, Brighouse’s early school days were quite the opposite. Born in 1940, his memories of attending grammar school in Leicestershire are miserable.

“I was school phobic. I would weep at night, I would be physically sick in the morning – this lasted for half a term until my dad lost his job and we moved to Lowestoft.”

On the first day at his new school his eldest brother agreed to check on him at break time. “But when I met him I said, ‘You can push off, I’m perfectly happy here, I like this place’. I remember the first school in black and white: the second in colour.”

Why the difference? At the first school he was tested each week. Students sat in rank order and were treated that way too. The second did none of this: “They made everybody feel they were special. They were fantastic teachers.”

His favourite, Mr Spalding, taught history and inspired him to study it further. “He was a terrific person. He was the archetypal after-the-war, been-in-the-war, rode a sit-up-and-beg bike, smoked a pipe, you never knew quite where he was coming from; he would argue one thing one lesson then come in the following lesson and argue the exact opposite; made you do this and that; ran the school debating society, collected stamps, was a fisherman as well, an angler. I kept in touch with him until… well maybe probably a year or two before he died. I thought he was a fantastic guy.”

After several attempts, Sir Tim secured a place at the University of Oxford and thoroughly enjoyed his time there, though initially he felt out of his depth.

“Nobody went from my school to Oxford. I remember being horrified, rolling into an Oxford college to find these hundreds of public schoolboys, all of whom read everything that you could ever read, and I’d only ever read about two or three books.”

After four years he left with his degree and a PGCE, and headed into teaching.

By age 26, he was a deputy headteacher in a South Wales secondary modern but left to pursue a job in education administration. “Educational administrators after the war, there was a number of them, and they were amazing . . . I wanted to do that sort of thing – it looked fun!”

For the next two decades that’s precisely what he did, eventually becoming education lead in Oxfordshire followed by four years as professor of education at Keele University. In 1993 he took his post as chief education officer in Birmingham, just in time for Patten to make his ill-judged claim.

“He made it within three weeks of my arriving in Birmingham. And don’t forget, I was going back into local authority administration, so within three weeks, that was all over the press.”

Sir Tim felt he had no choice but to pursue a complaint. “The fact that I won it and gave [the settlement money] to inner city education, and the fact that during the 10 months of the case, the politicians in Birmingham said, ‘You don’t want to tangle with him, he takes on secretaries of state, so if he says something – listen’, did mean that I could take lots and lots of risks and I knew the politicians wouldn’t try anything.”

During his time, Birmingham school results constantly increased and he became renowned for kindnesses, sending more than 5,000 handwritten letters of congratulations to teachers, and even turning up with champagne to one school after a tough Ofsted inspection.

What prompted this? “Blummin’ hell…that’s about being human!” he booms. “It isn’t that I won’t confront difficult situations where people have made a balls-up of something, because I have, and I do, and I would. But I do think they deserve dignity. And if somebody has not made a success of a particular school, they may have made a success of it earlier on – they may have been a very good head in another place or they may have been a fantastic deputy or they may be fantastic with difficult kids.”

This focus on the positive also characterised Brighouse’s time as London schools “tsar” in the early 2000s when he led London Challenge, a programme of support at a time when the capital’s schools were struggling. Sir Tim made it his business to talk schools up, telling teachers they were wonderful and getting them sharing practice. Debate rages about its effectiveness, but London GCSE results are now noticeably higher than the rest of the country, and it has confirmed in many people’s minds that “the Brighouse effect” is a real thing.

The interview winds down and he notices a colleague, nearby, who he motions to come sit with us. By the time he leaves, he is flanked by friends. The next day he sends an email in which he encouragingly writes “you will change the world”. It’s a small kindness, but a symbolic one. You can’t help but believe he says it to everyone; but you also get the distinct feeling that he believes it of everyone, too.

IT’S A PERSONAL THING

If you were invisible for a day, what would you do?

Oh my God! I don’t know. I’d probably . . . gosh, that’s an impossible question. Really tough. Are you inviting me to do something wicked? Um . . . I think I’d want to change all the draft legislation on the Secretary of State’s desk and invite his or her signature.

What’s your favourite book?

War and Peace. I read it for the first time as a challenge in retirement; thought I wouldn’t be able to read it – it’s a very long book – and wish I’d read it when I was 17 because it tells you so much about history and historians, writing and human nature. It’s an amazing book.

What was your favourite childhood toy?

Toy trains, yes.

Where would you like to go on your next holiday?

The islands of Scotland.

What are your hobbies outside education?

I’m keen on cricket and I’ve been a season ticket holder at Oxford United since about the 1970s. It’s a labour of love at the moment.

How do you spend time with your family?

Well I’m married to Liz, who is Labour leader of Oxfordshire County Council. We’ve got four children: two in America, two here, all with partners. We’ve got eight grandchildren and we saw all the American ones in the summer last year, and the rest we see here when we can. Just this morning I dropped one off for breakfast at school! So I get to see quite a bit of them.

Your thoughts